Typical street scene in Santa Ana, El Salvador. (Photo: iStock)

IMF Survey : Countries Explore Sales of Nonfinancial Assets to Help Reduce Debt

May 8, 2013

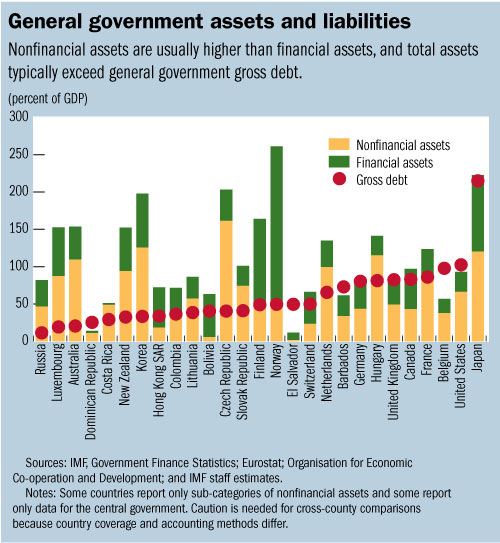

- Nonfinancial assets are often larger than financial assets

- Data coverage on government assets still has many gaps

- Use of nonfinancial assets for debt reduction remains limited

Governments across the world are exploring whether they could use their nonfinancial assets, such as land and buildings, to help ease their deficit and debt burdens. Yet according to a new IMF study, it is still unclear how much revenue the asset sales can really yield.

Wine cellar in Capian in southwestern France. In 2013 the city of Dijon in France sold off half of its municipal wine cellar to help fund social spending. (photo: Newscom)

Deficits & Debt

As governments run out of ways to trim budget expenditures, many are looking for alternative ways to improve their fiscal pictures. But generating revenue from sales of nonfinancial assets tends to be more difficult than privatizing public enterprises, in particular where assets include mostly infrastructure. According to the study, options include the collection of user charges, such as road tolls, as well as streamlining public administrations and exploitation of natural resources.

The study takes stock of the nonfinancial assets held by governments in thirty-two economies. For eight advanced economies it examines to what extent these assets have been used to create new funding sources and reduce debt. The study is the first to provide such a comprehensive cross-country comparison by using data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Eurostat, national authorities, and the IMF’s own Government Finance Statistics database.

“The analysis should help government finance officials arrive at a better indicator of their governments’ net worth,” said Elva Bova, an economist with the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department and co-author of the study. “Once they have this picture, they can begin to decide things like whether to sell some of the assets, or whether they can be more efficiently managed—perhaps by leasing buildings or setting up user fees.”

Snapshot of nonfinancial assets

Nonfinancial assets, when reported, comprise mostly structures—such as roads and buildings—and land. In most cases, the value of these assets has increased over time reflecting increasing property and commodity prices in the early 2000s. Nonfinancial assets can also include a variety of other assets such as computer software, research and development, and valuables such as works of art, precious metals, and gemstones.

The levels of reported nonfinancial assets differ widely across countries, averaging 67 percent of GDP and ranging from highs around 120 percent of GDP for the Czech Republic, Japan, Korea, and Latvia, to lows near 25 percent of GDP for Bolivia, El Salvador, and Switzerland. One reason for the wide range stems from the various ways data is reported and collected—for example, only a third of countries reports the value of land. The contrast also results from differences in the structure of economies and policies on holding assets, such as the role of the public versus the private sector in providing services.

For most countries in the sample, the value of nonfinancial assets held by governments is higher than the value of financial assets (see chart), and total assets are in most cases above gross debt. For example, in Australia the higher share of nonfinancial assets is due to its large natural resource assets. However, nonfinancial assets are sometimes underestimated in official accounts if the value of natural resources is not reported in the statistics, as is the case for example in Canada.

Subnational governments hold a large portion of nonfinancial assets in many countries, with their holdings totaling more than one-half of total nonfinancial assets. The share is particularly high in federal states, like Canada, Germany, and the United States.

Using nonfinancial assets to reduce debt

Looking in more detail at eight advanced economies, the study finds that most have recently laid out strategies for improving reporting and management of nonfinancial assets. However, so far, little revenue or savings have been obtained, when compared to the size of deficits and debt.

In some cases this was related to the costs of relocating offices of the public administration when buildings were sold (France), or reduced availability of assets after earlier privatization reforms (United Kingdom), or due to large parts owned by local governments (Japan, United States). Yet, the recent sale of spectrum rights in the United Kingdom—yielding proceeds of 0.15 percent of GDP, and the 2005 introduction of a road toll for trucks in Germany—yielding annual revenues of 0.2 percent of GDP, are examples of options to create new funding sources from nonfinancial assets.

Data gaps

The IMF study is the first to report and analyze data on nonfinancial assets systematically for a wide range of countries and drawing on multiple data sources. Yet large data gaps persist. For example, only a few countries report values of land and natural resource assets. For governments to be able to make decisions about whether to sell some of their nonfinancial assets, a first step will need to be an expansion and improvement of the data collected on nonfinancial assets.

“Currently, only thirty-five countries report information on nonfinancial assets to the IMF and OECD, and this is complicated by the use of different methods in both data collection and asset valuation,” said Robert Dippelsman, an economist in the IMF’s Statistics Department and co-author of the study. “For comparability purposes, moving toward one standard reporting method along with more consistency in valuation methods would be best.”