F&D Special Feature: Africa at a Crossroads: Learning from the Past and Looking to the Future

Investment in quality infrastructure will be critical for the region to adapt to and mitigate climate change

Cyclones, floods, locust swarms, and desertification of the Sahel are just some of the devastating effects of climate change on sub-Saharan Africa.

Increasingly intense and more frequent natural disasters, rising temperatures, erratic rainfall, and rising sea levels are taking lives and livelihoods, heightening food insecurity, and amplifying poverty. More than anywhere else in the world, sub-Saharan Africa’s hard-earned gains in living standards and advances in health and education are at risk of stalling or reversing.

Wide-ranging investments in resilient, green infrastructure are central to tackling the damaging effects of climate change. They can limit the economic impact of climate change—as these investments are up to twelve times more cost effective than frequent disaster relief—and can help sub-Saharan Africa leapfrog onto a path of prosperity. New, green investments also can help mitigate the impact of climate change without necessarily costing far more than traditional infrastructure. Private investment could also be spurred by resilient and green infrastructure, as it reduces risks of damage and other costs for businesses.

Done right, boosting resilience to climate change goes hand-in-hand with increasing opportunities for all, improving livelihoods, and reducing poverty.

How can infrastructure investment help?

Infrastructure plays a key role in adaptation and resilience to climate change. Consider, for example, sea barriers, broad beaches, drainage, and a host of other manufactured or nature-based infrastructure that shield against coastal flooding. Agricultural infrastructure, especially irrigation systems, and erosion and flood protection, increases crops’ resilience to extreme weather conditions. Better roads ensure food and other goods get delivered to markets on time. Robust homes and farming structures protect people, livestock, and food storage. Boreholes and deep tube wells preserve access to clean drinking water.

A healthy population, with access to clinics and hospitals, is less prone to weather-borne illnesses and will recover faster from injuries. An educated population, with access to schools and community centers, increases its earning potential and is better equipped to deal with the consequences of climate change.

Mobile networks ease access to social assistance payments, early warning systems for extreme weather events, and information on food prices and weather that informs farmers’ decisions on when to plant, irrigate, or fertilize—enabling climate-smart agriculture.

Electricity plays an overarching role as it powers much of this infrastructure, including drainage and irrigation systems, homes, health and education buildings and equipment, and mobile devices. With economic development and a rapidly growing population, sub-Saharan Africa’s energy demand could potentially multiply its greenhouse gas emissions from current low levels.

Substantial development partner financing and technology transfers (see below) will be needed to support investments in green industrial development and a gradual shift to renewable energy, such as solar, wind, and geothermal power.

Given the region’s dearth of industrial and energy infrastructure, there is an opportunity to ensure new infrastructure is resilient and green. In the meantime, investments to support near-term viability of existing infrastructure will also be needed. For example, hydropower currently generates one-fifth of sub-Saharan Africa’s electricity, and its susceptibility to droughts can be reduced through dams and reservoirs.

Of course, to be truly effective, these infrastructure investments would benefit from technology transfers from more advanced economies and broader reforms to advance health care, education, social assistance, and especially access to finance for households and businesses—empowering them to build their own resilience to climate change.

Maximizing effectiveness

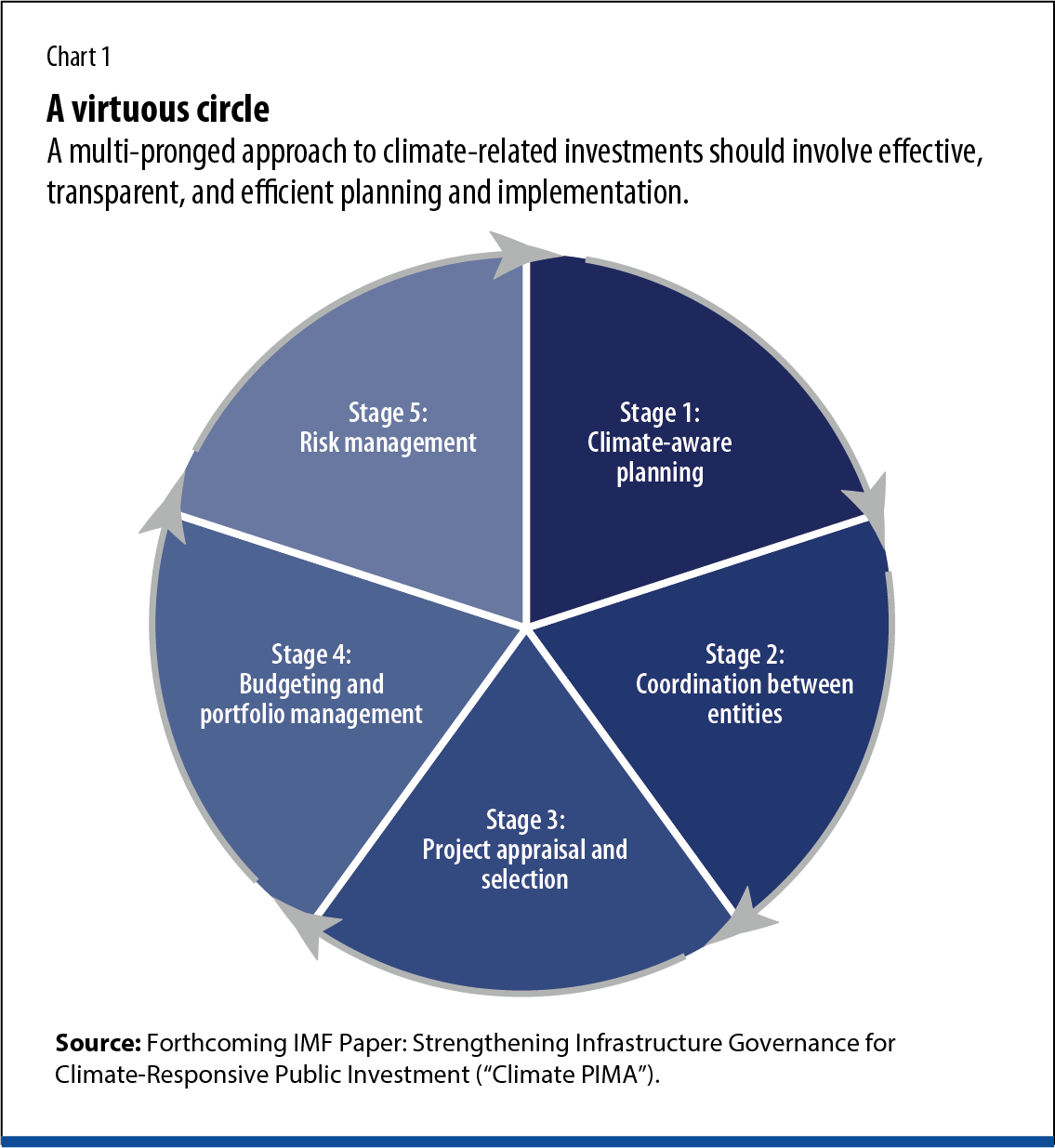

Rapid scaling up of infrastructure investment carries large costs and risks. Above all, will spending on public investment translate into useful infrastructure? White elephant projects from around the world that are over budget and underused quickly come to mind. Avoiding these pitfalls calls for a multi-pronged approach to investment, centered around effective, transparent, and efficient planning and implementation (Chart 1).

To this end, the first step is for countries to develop a climate strategy that factors in and addresses rising climate risks as well as the countries’ commitments to Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement. Each country’s strategy should be linked with its growth strategy and should include the cost of necessary infrastructure investments across all sectors (e.g., agriculture, health, education, telecommunications, etc.).

Second is the even more challenging task of prioritizing proposed infrastructure investments. Project appraisal and selection must incorporate climate-related analysis and criteria as well as the availability of financing. This requires project planning and preparation to be coordinated across the public sector, because a single investment can involve multiple government ministries and agencies as well as subnational governments. For example, a project on solar-powered irrigation in rural areas could potentially involve the ministries of agriculture, energy, environment, and social welfare.

The next step is to integrate the investments into medium-term budget frameworks (which usually look ahead over a 5-year horizon) in a way that supports transparency, predictability, and credibility. For instance, when countries are formulating budgets, they should explicitly spell out the expected climate impact of each investment and how it aligns with the country’s climate strategy. In some cases, a country may want to require analysis of the climate impact of any new investments, such as their effect on emissions reduction or preventing damage from climate shocks. Once projects are completed, measuring the climate impact of an investment against expectations helps ensure accountability.

The final step is to identify and manage climate-related risks that affect infrastructure planning and implementation. For example, how might future changes in technology or government policy—such as lower cost renewable energy technology or carbon pricing—impact the asset value of the planned infrastructure investment? What implementation obstacles might arise from potential climate shocks? High-level committees can help identify the risks, ensure appropriate financing mechanisms are in place (e.g., financial buffers for climate-induced damage during construction), and remove obstacles to ensure projects get completed on schedule and within budget. Many of these risks and plans to manage them could usefully be included in a country’s climate strategy.

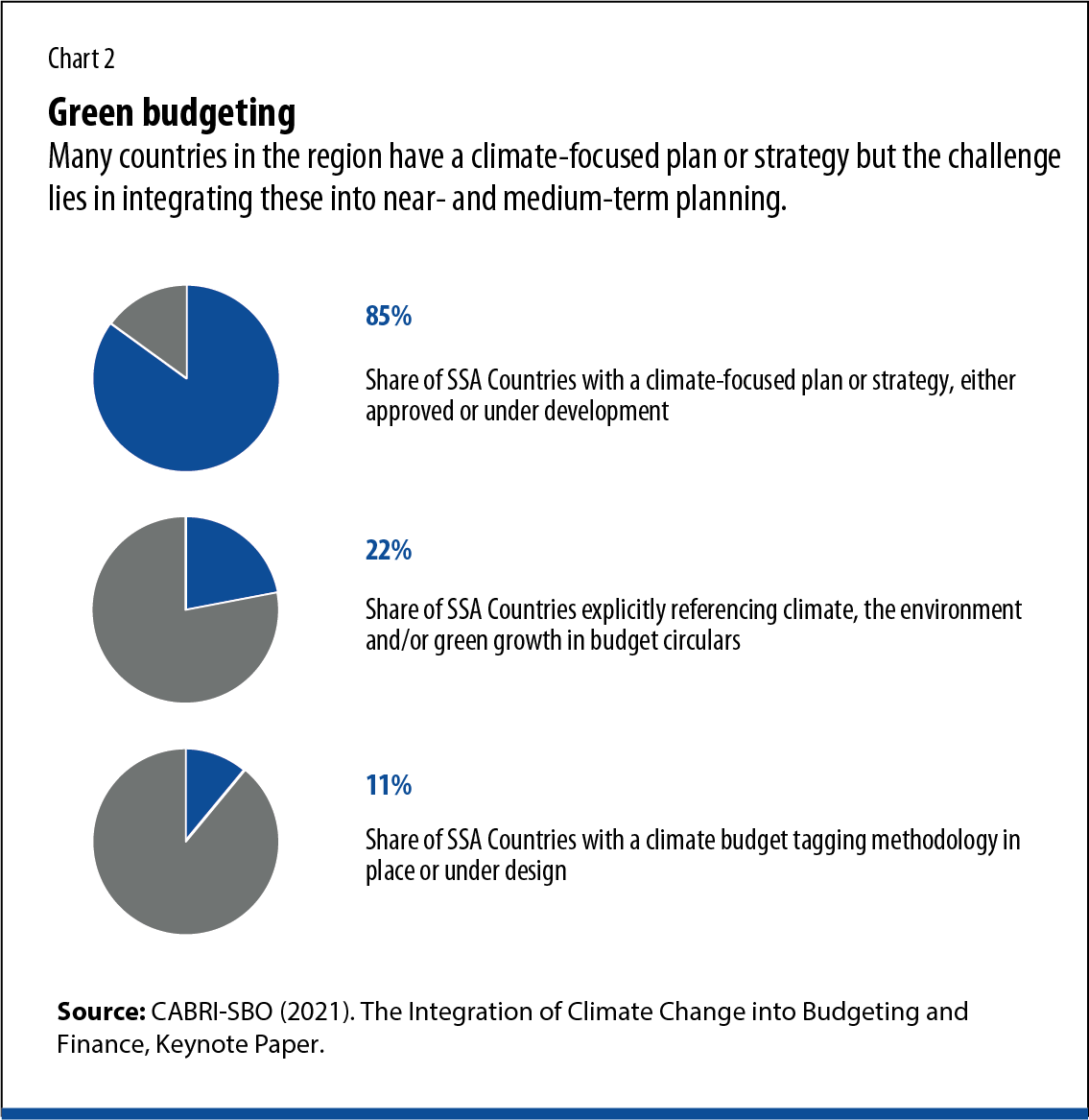

The IMF is helping countries incorporate all stages of this approach through capacity development focused on the IMF’s green public financial management framework (green PFM) and climate public investment management assessment module (C-PIMA). Initial assessments of several sub-Saharan African countries show that they have established climate strategies and climate-aware planning (Chart 2). The challenge lies in integrating these strategies into near- and medium-term fiscal planning. For example, more political support and better coordination across the public sector is needed for climate change to be considered when evaluating public investment projects and integrating climate projects into near- and medium-term budgets.

Similarly, some countries’ medium-term fiscal frameworks include climate-change risks in macro-fiscal projections but key climate-related risks to public infrastructure typically are not identified.

Securing financing

Equally important to maximizing the effectiveness of climate-related public investment is securing financing for it.

Infrastructure investments needed to boost resilience in sub-Saharan Africa and, over the long-term, curb emissions growth in the region will be expensive. At COP26, the African Group of Negotiators indicated that, beginning in 2025, a minimum $100 billion per year would be needed over the next decade and a half, an estimate that does not include maintenance of this new infrastructure.

This is much more than sub-Saharan African countries can afford on their own, particularly amid their increasing debt levels in the wake of the pandemic. But it is within reach if bilateral and multilateral development partners step up concessional financial assistance. In many cases, such as that of climate funds, procedures for countries to access this financing could be simplified and sped up.

For their part, the region’s policymakers need concerted efforts to mobilize domestic revenue and improve management of public investments and finances, be they climate-related or more general. Such actions would demonstrate a readiness to effectively utilize resources from development partners to boost sub-Saharan Africa’s resilience to climate change through green infrastructure investments.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.