Sweden -- 2009 Article IV Consultation, Concluding Statement of the IMF Mission

June 15, 2009

Describes the preliminary findings of IMF staff at the conclusion of certain missions (official staff visits, in most cases to member countries). Missions are undertaken as part of regular (usually annual) consultations under Article IV of the IMF's Articles of Agreement, in the context of a request to use IMF resources (borrow from the IMF), as part of discussions of staff monitored programs, and as part of other staff reviews of economic developments.

Up to the Spring of 2008, the Swedish economy boomed

1. Since 2002, Sweden has thrived in buoyant global conditions, reflecting strong policies and a composition of output—investment goods and consumer durables—particularly favored by the global boom. And two of its banks, heavily funded on global wholesale markets, built large exposures to the Baltics, yielding high returns. Inflation remained low, the current account and budget balance in significant surplus, the long run public sector net worth remained positive, and unemployment trended down.

2. But the same global factors which supported this record also left Sweden highly exposed to the post Fall-2007 international financial crisis. As an investment goods and consumer durables exporter, Sweden was hurt by weakening external demand long before the major contraction in global trade late in 2008. Though its banks had limited exposure to risky US assets, some had troubled exposures in the Baltics. As global wholesale markets closed, liquidity crunched. Having surfed the earlier global wave, the Swedish economy has been hit hard by its crash.

Policy action has steadied confidence, but the tide is still out

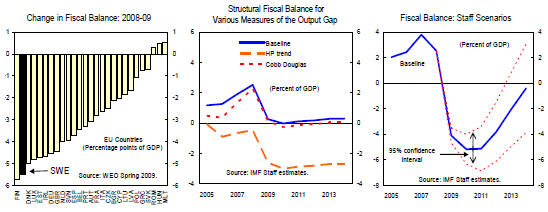

3. The authorities have responded promptly and appropriately to these challenges, and immediate concerns with financial sector stability have been addressed. During 2008 and into 2009, the full range of measures typical elsewhere was implemented reflecting the agreed EU response: Riksbank total lending has increased significantly, at lengthened maturities, and it now also provides dollar liquidity; the monetary policy stance was decisively relaxed, led by a reduction in the policy rate to ½ a percent; deposit guarantee coverage has increased; governance reforms in key banks have been made; a credit guarantee and a bank recapitalization scheme have been established; and on the fiscal side, full operation of automatic stabilizers and a discretionary budget loosening for 2009 is underway—taking the budget from a surplus of 2½ percent of GDP in 2008, to a deficit of 4 percent in 2009, one of the largest shifts in the overall fiscal balance in the European Union since 2008. Much has been done.

4. These steps have supported the economy and helped to address downside tail risks, with financial market indicators showing some easing of pressures since the new year. But as a small open economy dominated by still adverse global developments, the tide has not turned. With GDP declining slightly through 2008, the mission projects it to fall 6 percent in 2009, leveling off in 2010, with a modest quarterly recovery starting in the middle of that year. In this context, unemployment will rise significantly, albeit attenuated by the reforms to labor market structures and income taxation in recent years.

Policy for 2009–10 should continue to aim to minimize the fall

5. Immediate prospects for recovery are very dependent on developments abroad. As a producer of goods disproportionately favored by the prior global boom, Sweden was one of the first into the downturn. And if demand for those goods recovers slowly relative to other components of global demand—as seems likely given large output gaps, credit constraints, and wait-and-see behavior by investors and consumers abroad—Sweden could be one of the last out of recession. This is possible even taking account of the strong stabilization measures adopted, without which the outcome would have been considerably worse.

6. In this adverse context, maintenance of confidence is critical. Thus, bad as the downturn may turn out to be, any case for more stimulative countervailing policies should carefully weigh risks of unintended consequences. Accordingly, with fiscal policy still credible over the medium-term, automatic stabilizers should operate unimpeded. With inflation pressures abruptly diminished, support for activity from monetary action—but from the conventional rather than the unconventional side for now—should remain aggressive. And steps should continue to be taken to ensure that the financial stability framework is ready to address downside tail risks, and to lower the likelihood of such events. This combination of fiscal, monetary, and financial stability measures, elaborated below, will boost Sweden’s resilience in a testing environment.

Large fiscal stabilizers should continue to operate, along with the stimulus underway

7. Sweden entered the downturn in good fiscal health. Debt was low and falling, the framework of rules guiding policy has been adhered to and remains in place, even now, and as measured at the outset, the “fiscal balance sheet” reflecting long run sustainability was strong.

8. Nevertheless, the case for additional discretionary fiscal activism to offset the downturn is not persuasive. The scale of the fiscal action underway—as appropriately measured by the change in the headline balance—is, on IMF estimates, already one of the largest in the European Union (See Figure). Furthermore, plausible estimates of potential output yield widely varying estimates of the structural balance and the fiscal outlook, and it is unclear how much public debt will rise due to financial sector rescue operations that may prove to be necessary. In addition, the stabilizers are large, the multipliers are small, and with estimates of medium-term potential output growth being lowered globally, the long run fiscal strength apparent at the outset of the crisis will need to be reassessed.

9. Accordingly, the scale of the change in the structural fiscal balance projected by the mission—a weakening of 2¼ percentage points of GDP in 2009, and a further ¼ percentage point in 2010—appropriately balances the need for a decisive fiscal response to a uniquely sharp fall in demand, with sustainability concerns. The stimulus package includes permanent cuts in personal, social contributions and corporate income tax. These steps have merit in supporting supply side efficiencies, even though their immediate demand impact is likely limited.

10. And the fiscal rule targeting a surplus of 1 percent of GDP over the cycle should remain. As affirmation that this surplus goal remains the centerpiece of medium-term fiscal policy, the firm commitment to the nominal spending ceilings should be maintained, with matching adjustments being made to these ceilings to offset the net revenue impact of any further discretionary tax reforms on projected budget balances. The Fiscal Council could play a useful role in monitoring compliance with the letter and the spirit of these principles. This approach allows automatic stabilizers to operate unhindered on the revenue side, while accommodating considerable latitude for this on the spending side also. And if the economy turns out weaker than expected, the fiscal response should continue to focus on accommodation of the automatic stabilizers in view of their large size, and reflecting the small size of the multipliers, and sustainability concerns.

Monetary policy is appropriate

11. On the monetary side, as internationally, inflationary pressures eased abruptly from Fall 2008 and a modest undershoot of the inflation target—1 to 3 percent—is likely this year. However, with underlying inflation still moderate, risks of sustained disinflation appear low: short and long term indicators of inflation expectations point this way, with many having rebounded from troughs at end-2008, partly reflecting significant depreciation of the exchange rate since the Fall of 2008. Accordingly, the case for immediate further relaxation is not compelling. And only if inflation expectations fall significantly and on a sustained basis, should consideration be given to the various Quantitative Easing options. And nor is there yet good evidence of failures in particular credit markets that would warrant further “credit-easing” measures.

12. Moderate inflation expectations are one set of indicators suggesting that the exchange rate is not too far below fair value. Given the particular exposure of Sweden to the global collapse in demand for investment and durable consumer goods, a good part of the recent depreciation is likely an equilibrating adjustment—securing a necessary relative price change to the persistent real shock to global demand for these goods. Accordingly, along with the reforms to labor market structures and income taxation in recent years, it will play a key role in containing increases in unemployment.

Additional proactivity may strengthen the financial sector further

13. Financial sector fragilities derive from Baltic exposures, severe domestic and Nordic recessions, and banks’ reliance for funding from global wholesale markets. All three interrelate through their impact on market assessments of bank capital adequacy.

14. Following the appropriate stabilizing actions taken since the Fall of 2008, the most recent step was publication of stress tests by the authorities. The severity of the underlying scenario assumptions, the bank-by-bank analysis, and the transparency in reporting the results all reflect best international practice in such exercises. But market concerns about the adequacy of Swedish banks’ capital—as reflected in bank stock prices, CDS spreads, and interbank transactions—remain, albeit that such concerns vary across banks, and that they have eased somewhat from recent troughs in the context of the stabilizing global financial environment. This indicates, as in other countries, that the regulatory minima are regarded as insufficient, even with the broad range of public actions in support of bank stability in place. Without that exceptional support, the capital ratios required by markets would be higher still.

15. In designing financial sector stability policy, capital ratios signaling both institutional and market resilience to private investors and depositors, even in the absence of extraordinary stabilizing support, should ultimately be targeted. Significant steps towards such ratios would best be required over a relatively short time horizon. This would boost resilience to short term shocks, reduce scope to meet higher capital requirements by curtailing credit supply, reduce contingent claims on taxpayers, and it would anticipate eventual exit from the extraordinary support measures.

16. This establishes a case to raise regulatory requirements soon. In cases where banks’ capital falls short of such increased regulatory requirements, straightforward recapitalization or resolution is recommended. If rights issues to private investors prove inadequate for systemic institutions to achieve the new target capital levels, public equity—injected at prices appropriate to ensure protection of taxpayer interests—and implementation of a bad-bank model should be undertaken as needed. Given the fiscal fundamentals, this is unlikely to unsettle confidence in fiscal sustainability, even if eventual recoveries turn out to be limited.

17. This approach will require continued close cooperation of all the domestic authorities concerned—the Ministry of Finance, the National Debt Office, the Riksbank, and the Financial Supervisory Agency—with each playing key roles in encouraging early capital increases. It will also require continued close coordination with host country authorities of foreign subsidiaries of Swedish banks.

18. This would constitute a strengthened preemptive strategy. And to address risk that it is overtaken by events, continued contingency planning is also appropriate, fully coordinated domestically and with the relevant regional authorities. As part of this, we see scope for further review of the toolkit for supervisory intervention to ensure robustness. There is also scope for further increases in international reserves beyond those already announced.

19. Beyond this, several additional steps are needed. The institutional capacity of the Financial Supervisory Agency should be boosted, including by prompt determination of strengthened arrangements for its ongoing resourcing. In this context, it should expand its supervision to deposit taking non-bank financial institutions. Given sizable international operations of large Swedish banks, further concerted efforts to strengthen cross-border crisis resolution mechanisms, coordinated with EU partners, should also be made. And as, over time, banks will need to refocus their funding away from wholesale sources, the pricing and collateral arrangements for Riksbank liquidity should be appropriately adjusted, once the immediate crisis passes.

We are grateful for the warmth of the welcome afforded to us during our visit to Sweden.

IMF EXTERNAL RELATIONS DEPARTMENT

| Public Affairs | Media Relations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-mail: | publicaffairs@imf.org | E-mail: | media@imf.org | |

| Fax: | 202-623-6220 | Phone: | 202-623-7100 | |