(Version in 日本語)

Japan's economic progress over the past year has been impressive, with strong growth, and inflation, investment, and credit growth all heading in the right direction. But that progress is largely the result of last year’s sizable fiscal and monetary stimulus—the first two arrows of “Abenomics”. Now, the economy needs to transition to more sustainable, private-sector led growth. A hike in wages could be just the push needed to propel that shift.

As the ongoing annual wage-bargaining round draws to a close, total earnings are set to increase this year for employees at some well-known car manufacturers. But, in the past, these increases have not trickled down to higher basic wages at small and medium-sized enterprises and to non-regular workers. This is problematic as higher inflation without higher incomes can hardly be characterized as a successful reform.

The argument for higher wages

For many years, nominal basic wages have been declining despite generally tight labor-market conditions. Real wages too have fallen despite solid productivity growth.

So, labor’s share of national income has dwindled, from around 66 percent at the turn of the millennium to around 60 percent today. The average Japanese worker has been dipping into his savings to finance consumption growth. But there’s a limit to how far he can do this. The savings rate as a percent of disposable income has declined from around 5 percent a decade ago to close to zero today, leaving little further room for spending from savings, amid a continued high financing demand from the government that still runs a sizeable deficit.

Looking forward, real wages are set to come under even greater pressure this year and next with higher underlying inflation and successive increases in the consumption-tax rate.

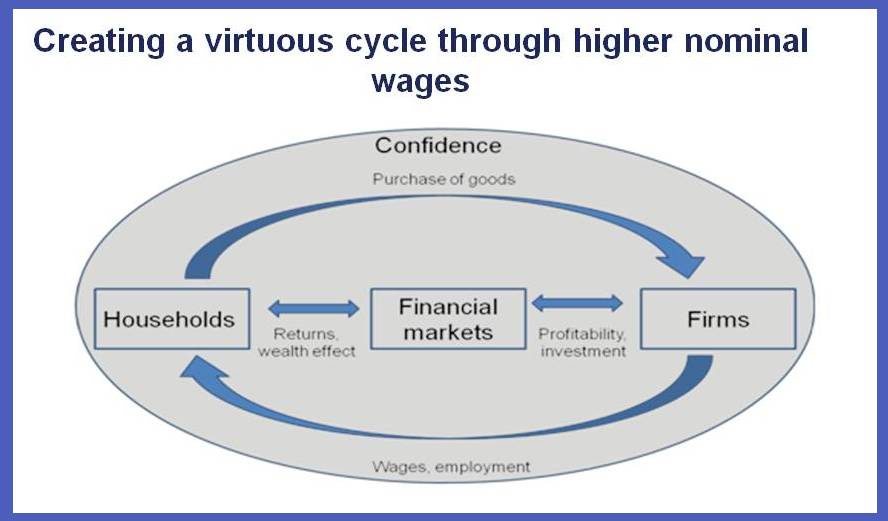

So the message is clear: higher wages are needed to help to break the deflationary spiral and establish a virtuous growth cycle. Insofar wage increases are passed on to consumers by firms, higher nominal wages would allow the Bank of Japan to meet its inflation target more rapidly, without overburdening monetary policy. Insofar real wages increase, larger pay packets would also support aggregate demand and create favorable conditions for firms to raise their investment.

To be sure, wages are just one ingredient for a successful transition to self-sustained growth. It also requires shaking off other remnants of the deflationary mindset. Financial institutions need to actively pursue new lending opportunities at home and abroad rather than accumulate excess reserves at the Bank of Japan. Exporters need to take advantage of the weaker yen by trying to gain a larger market share. And firms will need to put their retained earnings and increased valuations to good use, by raising investment, and increasing dividend payments, aside from offering higher wages.

Factors that prevent wages from rising

Compared to other countries, Japan stands out in having downward nominal wage flexibility and upward rigidity. It is indeed surprising that with the Bank of Japan’s 2-percent inflation target gaining credibility and underlying inflation picking up markedly, wages still appear to remain rather sluggish. The blame lies with structural factors which have long depressed wage growth in Japan as well as the challenge to overcome a coordination problem now that economic conditions are changing:

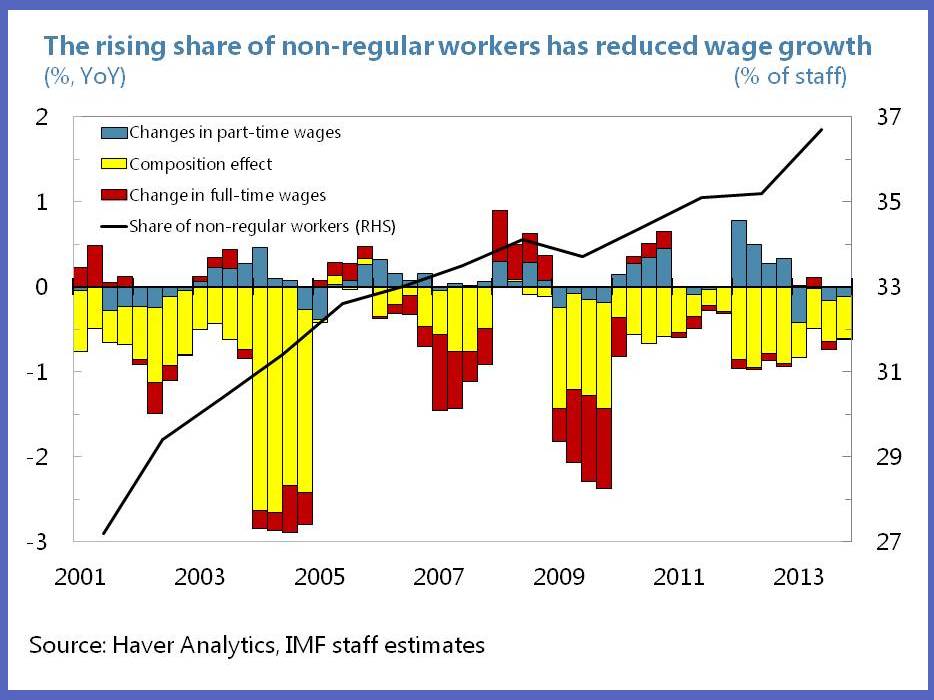

- The emergence of non-regular workers amid generally low horizontal mobility of employees. Although this has contributed to greater labor market flexibility, firms and non-regular workers have fewer incentives to invest in firm-specific human capital, hampering productivity growth. Since these workers’ wages are lower, their growing share has pushed down aggregate basic wage growth.

- Competitiveness concerns from persistent exchange rate appreciation prior to Abenomics in the context of increased foreign competition and technology catch-up. The result has been limited domestic wage increases and more overseas production and outsourcing.

- A weak SME sector—which accounts for close to 70 percent of employment—that even under last year’s buoyant conditions may not have benefitted from Abenomics due to higher energy, as well as other intermediate imported goods costs as a result of the weaker yen.

- A coordination problem. Given Japan’s history of low growth and deflation, lack of formal or de-facto wage indexation, and segmented labor markets, if left to the market, firms will want to free-ride on wage increases by other firms. This coordination problem has been amplified by the declining importance of the annual wage-bargaining round in April (“Shunto”), with firm-level profitability now playing a dominant role and bonuses and overtime payments comprising important shares of compensation, especially for larger firms.

Measures to raise wages

The structural factors will have to be addressed through Abenomics’ Third Arrow: ambitious growth reforms to create a more vibrant and competitive corporate sector with greater and more equal labor force participation. For example, measures to reduce duality in the labor market and a gradual shift towards a model that combines labor market flexibility and security (“flexicurity”) could provide a boost to aggregate compensation growth.

But are there ways to enhance coordination in the near term? Prime Minister Abe has been relying on ‘moral suasion’, by explicitly asking profit-making companies to increase wages. As a natural extension of this strategy, the Abe administration also moved toward a wider policy of ‘social concertation’, by setting up the Tripartite Commission, in which the government becomes more directly involved in discussions with employers and trade unions. The government recently decided not to extend the 7.8 percent cut in wages of national public servants—which was introduced in 2012 to finance reconstruction spending and is now set to expire on April 1, 2014—which is also likely to push up salaries of local government workers.

Complementing these measures, tax incentives for raising wages have also been introduced. Specifically, a tax credit has been introduced equal to 10% of incremental labor expenses provided the firm’s wage bill rises by 2%—gradually rising to 5% by 2017.

To enhance effectiveness, these could be made permanent, or targeted more to increases in base wages only, while the tax credit could be raised, although this will likely give rise to well-known deadweight losses (firms receive incentives for wage increases they might have provided anyway).

Finally, Japan’s minimum wage is among the lowest in OECD countries. Tentative evidence (using prefectural data) suggests a positive relation between minimum and basic wages. Higher than usual increases in the minimum wage might therefore help to spur wage growth, although these may cause job losses among non-regular workers and in the small and medium-sized enterprise sector.