(Versions in 日本語)

Japan’s GDP declined by almost 7 percent in the second quarter, more than many had forecast including us here at the IMF. Many cite the increase in the sales tax this April for this decline. But that is not the full story.

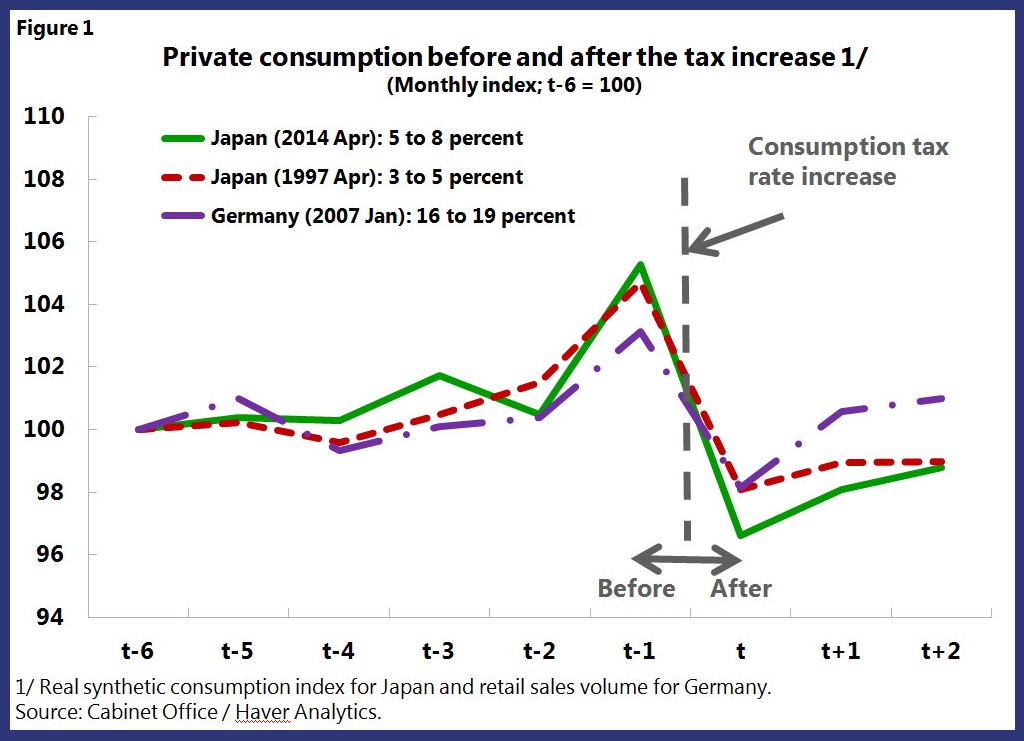

Yes, it is true that consumer responses to major tax increases are difficult to predict, and large spending swings are not unusual. We see this pattern in many countries (see chart) including Germany’s 2007 VAT increase, which had a short-lived impact.

But Japan needs to tackle other constraints on growth, such as lifting household and business confidence. In this regard, what is more important for Japan’s outlook now are its long-term policies. Abenomics has already made progress in ending deflation and jumpstarting the economy. With the near-term outlook looking increasingly uncertain, the government needs to move quickly on the third arrow of structural reforms.

Abenomics’ third arrow holds key for lifting expectations

Japan has announced a large number of structural measures since last year, ranging from raising female labor supply, agricultural and electricity sector reform, to deregulation and market opening. What is needed, however, is faster implementation and a more comprehensive approach to lift expectations—critical for maintaining confidence. Recent IMF staff research (see Balance Sheet Repair and Corporate Investment in Japan) shows that firms need first and foremost clarity about future growth opportunities before they start to invest.

Businesses need also more prodding to “unstash their cash”

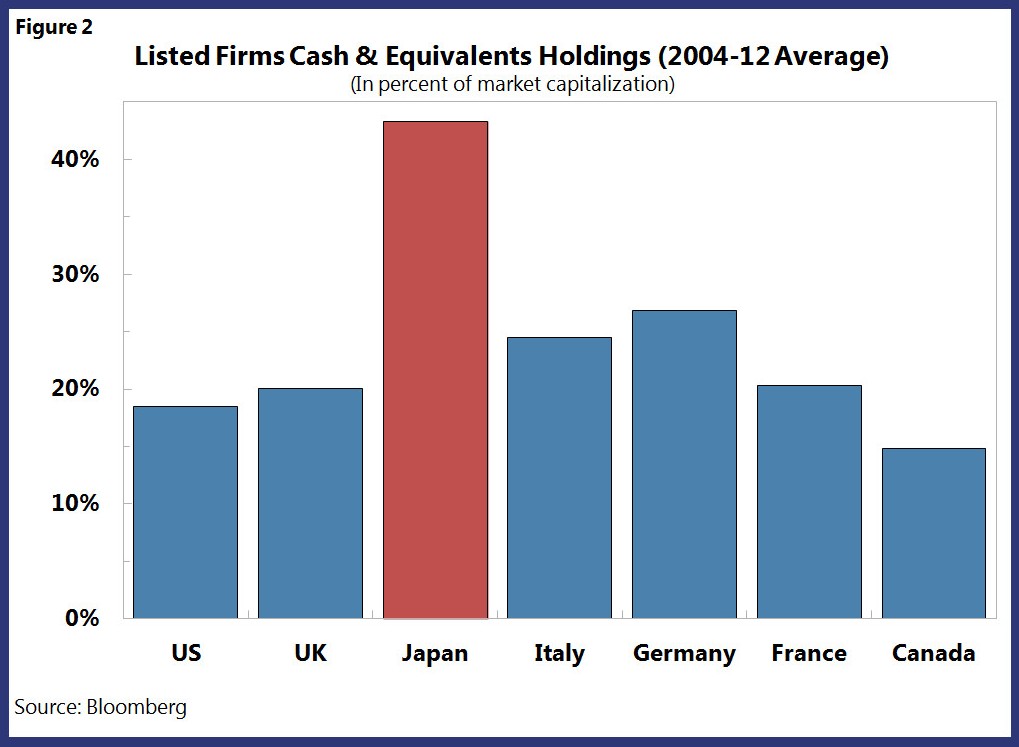

One of the most promising untapped growth resources are firms’ large cash holdings. Over the last decade, Japan’s average ratio of cash holdings relative to market capitalization exceeded 40 percent—more than double the equivalent figure for many other G-7 countries.

New IMF staff research (see Unstash the Cash! Corporate Governance Reform in Japan) suggests governance and legal framework reforms could lead to more efficient use of these resources. For instance, raising the number of external independent directors and other measures could raise activity––empirical evidence shows that firms with many external directors rarely hold large cash reserves. The government has already made important strides with recent amendments to the Company Act and the introduction of a Stewardship Code for institutional investors to enhance their roles as shareholders. Adoption of a corporate governance code for firms would be another important measure.

Address labor market duality to help with shortages

Shortages in Japan’s labor market are quickly becoming a growth bottleneck. An aging population and limited access to foreign workers are constraining labor supply, while growing demand for skill-intensive services, especially in the health area, is boosting demand.

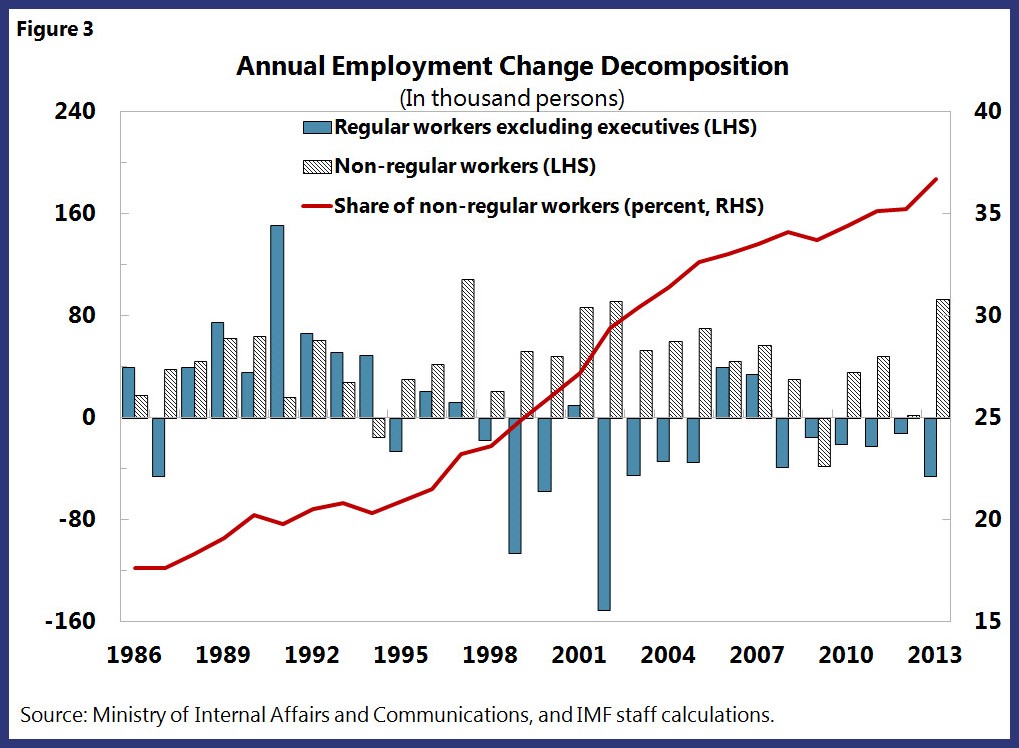

Japan’s segmented labor market is ill-equipped to cope. Most jobs in Japan still provide life-time employment (regular employment). But because of past cost concerns, the share of irregular employment with lower growth opportunities and weaker job protection has risen rapidly over the last decade.

Many highly educated women and younger workers hold these jobs, limiting their productivity growth and attachment to the labor market. Narrowing the differences between regular and irregular employment could reduce these inefficiencies and help supply talent to areas where it is needed most (see The Path to Higher Growth: Does Revamping Japan’s Dual Labor Market Matter?). There are no easy fixes: but tackle Japan’s labor market rigidities and you enhance its growth potential.

Abenomics needs to stay the course on fiscal and monetary policy

With the consumption tax increase, Japan has taken a first step towards addressing its biggest long-term challenge—reversing the rise of the public-debt-to GDP ratio at over 240 percent of GDP. This and next year’s consumption tax rate increase to 10 percent, would reduce the deficit by about 2 percent of GDP—an important down payment toward restoring fiscal sustainability. Fiscal risks will, however, remain large given the still sizeable future consolidation need of another 6 percent of GDP. To limit the risks of a sudden rise in interest rates, adopting a concrete fiscal strategy beyond 2015 is urgently needed and would afford the government to respond flexibly to downside risks.

On the monetary policy side, the Bank of Japan has made great strides in ending deflation for good. With inflation and inflation expectations increasing (chart)—a major achievement— real interest rates are declining and lifting returns on capital investments.

Exiting deflation would also remove other, difficult-to-measure growth effects, such as widespread risk aversion and investor passivism. We believe that the Bank of Japan’s easing policy is appropriately accommodative at the current time. But if progress in raising inflation were to stall, it should act swiftly and expand its asset purchases.

Japan’s post-consumption tax growth outlook is still favorable. But reforms need to march on as quickly as possible to eliminate key constraints on potential growth, and strengthen confidence. All three of Abenomics’ arrows matter, but the structural one is now key.