In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, Canada’s financial system held up remarkably well—making it the envy of its Group of Seven peers. This relative resilience was particularly impressive considering its most important trading and financial partner, the United States, was the epicenter of the crisis.

Part of Canada’s success story lies in the fact that its banking system is dominated by a handful of large players who are well capitalized and have safe, conservative, and profitable business models concentrated in mortgage lending—much of it covered by mortgage insurance and backstopped by the federal government. Notwithstanding such an enviable record and sound financial system, we need to keep an eye on certain financial risks.

Risks to watch

The IMF’s recent report on Canada’s economy raises some concerns in the wake of substantially lower oil prices. The economy’s two main domestic vulnerable areas are its overheated housing markets and high household debt.

Although household debt levels appear to have stabilized recently, they have increased to historical highs over the past decade, reaching over 150 percent of disposable income—one of the highest among member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

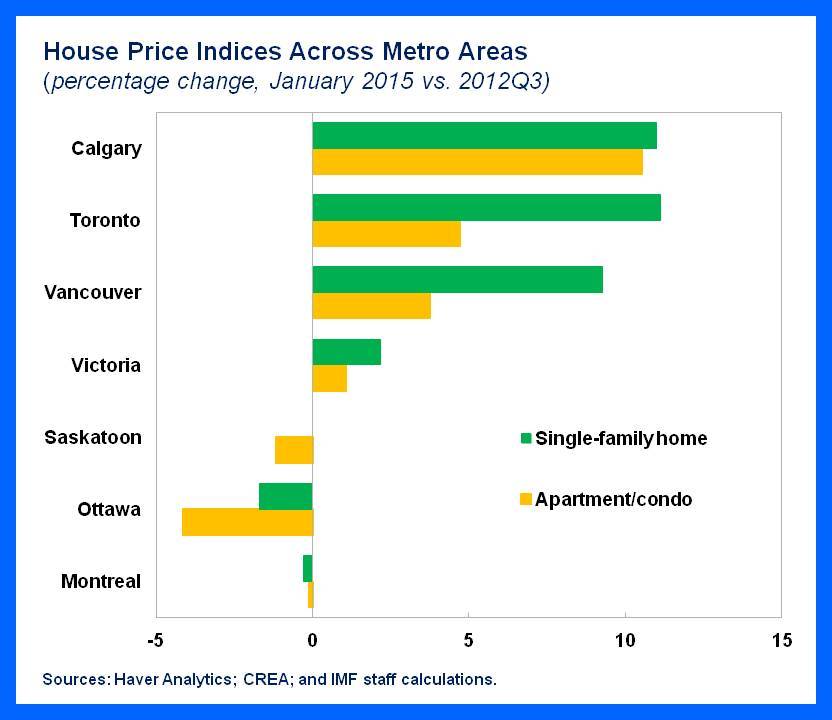

Meanwhile, house prices have risen more than 60 percent nationwide since 2000. Major metro areas have led the run-up in prices, including Toronto, Calgary, and Vancouver—the latter recently ranked second in terms of the lowest affordability globally after Hong Kong. But with weaker terms of trade, lower growth, and prospects of higher U.S. interest rates, Canada’s overvalued housing market may be cooling off. For example, there have been some recent signs that home listings to sales are rising noticeably in oil-rich Alberta, and we will need to keep an eye on the risk of a hard landing.

Over the past several years, Canada has taken numerous steps to reduce the economy’s vulnerabilities through policies designed to keep financial institutions and the financial system as a whole safer.

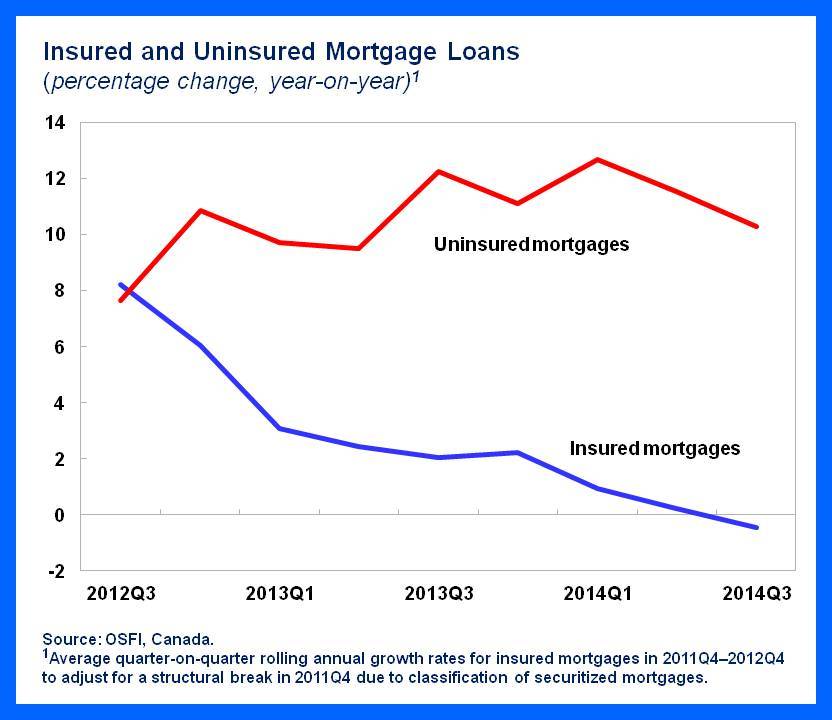

Slower mortgage credit growth and higher quality borrowers, for example, appear to be the direct result of tighter lending standards (such as lower amortization periods, higher down payments, and house price caps) on insured mortgages.

These steps may have been only partially effective in restraining credit growth. A possible sign of “leakage” from tighter financial rules in Canada—which is a general problem that countries can face after tightening such rules—involves the expanding role of uninsured mortgages. These loans with loan-to-value ratio below 80 percent are not subject to the same regulatory tightening. These now comprise the bulk of mortgage originations and help fuel housing demand. For example, house price increases concentrated in single–family homes in fast-growing real estate markets seem tied to uninsured mortgages. If financial risks start rising again, policymakers may need to take further action to tighten rules on these loans.

Over time, Canada would also benefit from reforming the government’s role in mortgage insurance and reducing taxpayer’s exposure to the associated risks. Limiting the federal backstop would increase private sector risk sharing and can further encourage prudence. Given the system’s current reliance on insured mortgages, however, changes would need to be gradual to steadily encourage the private sector’s role to expand as the public sector’s recedes.

Connecting the dots

What else can Canada do to improve resilience of the financial system?

Looking ahead, a broader issue is strengthening Canada’s policy frameworks designed to keep the overall financial system safe. But there is a healthy debate over what approach works best. While informal cooperation between key agencies worked well during the crisis, future shocks will inevitably look different. From our perspective at the IMF, having robust frameworks with more formal arrangements already in place to identify and respond to future shocks would enhance resilience.

Two key steps are worth considering.

First, providing a mandate for macroprudential oversight of the financial system as a whole to a single entity would strengthen accountability and reinforce policymakers’ ability to identify and respond to future potential crises. Such a body should have participation broad enough to “connect the dots” and form a complete and integrated view of systemic risks with powers to collect the required data.

Second, putting in place a coordination framework to support timely decision-making and test the capacity of both federal and provincial authorities to respond to crisis scenarios would benefit crisis preparedness. Extending the institutional arrangements and frameworks along these lines can help support both the capacity and willingness to act, especially at times of financial stress, and strengthen Canada’s financial system and economy.