Versions in عربي (Arabic), Français (French), Русский (Russian), and Español (Spanish)

What happens if advanced economies remain stuck in a long-lasting funk marked by tepid growth, low interest rates, aging populations and stagnant productivity? Japan offers an example of the impact on banks, and our analysis suggests that there could also be far-reaching consequences for insurance companies, pension funds, and asset-management firms.

You might argue that this scenario of economic malaise has already materialized; after all, interest rates and economic growth have been low since the financial crisis in 2008. The question is whether the post-crisis landscape represents a temporary departure from the pace of growth we’ve come to expect since World War II, or whether it’s the start of a new normal.

Notwithstanding the recent increase in long-term yields in some advanced economies, the Japanese experience suggests that we cannot be sure whether an exit from a low-growth/low interest rate trap is imminent or permanent.

Depressed margins

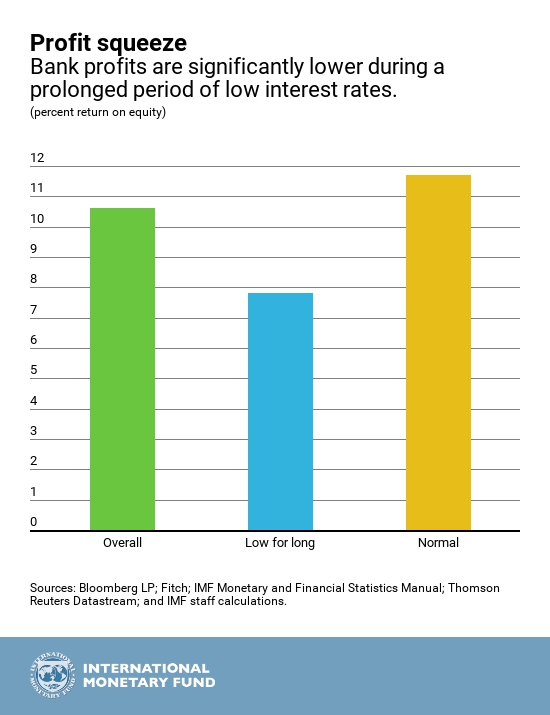

Chapter 2 of the IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report examines the likely impact of an extended period of stagnation. Some of the fallout is already apparent. The so-called yield curve, or the difference between short-term and long-term interest rates, has flattened. For banks, which generally borrow money relatively cheaply for short periods and lend for longer periods at higher rates, that means less revenue.

Banks typically also find it difficult to lower rates on deposits to below zero, so that lower rates tend to depress margins. And with a likely decline in demand for credit from households as the population ages and growth remains slow, higher lending volumes can’t compensate for low margins. By contrast, demand for fees-based and transactional services can be expected to rise.

Here’s a closer look at a scenario of long-term stagnation:

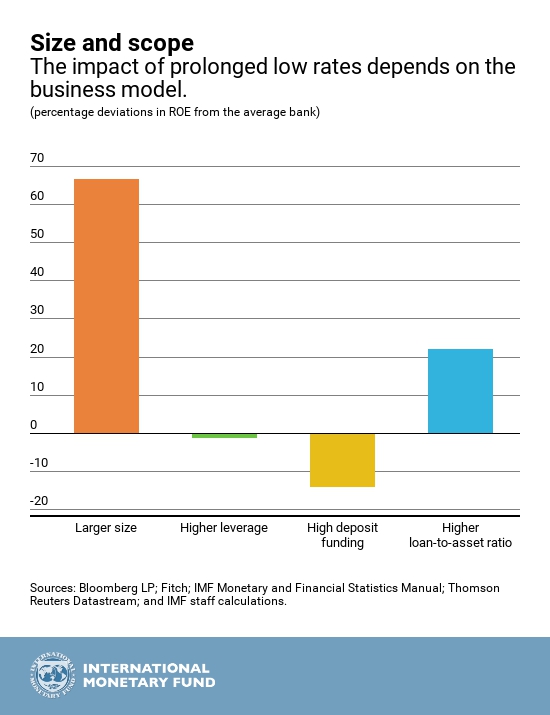

- Smaller, deposit-funded and less diversified banks will be hurt most in such a scenario. They may be pushed to reduce costs to preserve profits, and ultimately into mergers or bankruptcy.

- Larger banks are likely to diversify abroad as they seek new, more profitable outlets in emerging markets.

- Life insurance companies also face threats to their profits and solvency. Their assets, or investments such as bonds, are often shorter-term than their liabilities, or the policies they write. That means they may have to reinvest maturing assets at lower yields, while continuing to make high payouts on their policies. As a result, they may be forced to raise more capital.

- Pension funds, like life-insurance companies, may need more capital. They would also have to reduce benefits in the long term. The transition from defined-benefit to defined payment pension plans continues.

- Asset managers see their market share grow as more people invest retirement savings in stocks, bonds and mutual funds. They may also grab business from insurance companies as savers seek alternatives to lower-yielding guaranteed products such as whole-life policies.

How should policymakers and regulators respond to these shifts in the financial landscape? Here are some general principles:

- Make it easier to consolidate or liquidate failing firms, allowing remaining banks to improve their profitability

- Limit incentives for banks to take on excessive financial risk

- Introduce frameworks that recognize the financial conditions of insurance companies and pension funds by consistently evaluating assets and liabilities based on economic value, if they haven’t yet done so.

In addition, asset management firms may need closer supervision as their its share of the financial system continues to grow. In particular, regulators may need to monitor threats to financial stability posed by the increasing popularity of passive index-linked funds, which may reduce diversity of investments and encourage herd behavior among fund managers.

The IMF will release more analysis from the Global Financial Stability Report on April 19.