Higher temperatures, extreme weather events, and the reliance on climate-sensitive sectors such as tourism and agriculture are just some of the challenges facing Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). In such a diverse region, climate change impacts countries differently, and presents a set of challenges as varied as the countries themselves.

But climate change also offers opportunities. The climate transition could help boost growth and generate new jobs while supporting the recovery from the pandemic and improving health outcomes. The transition will be facilitated in some LAC countries by their natural endowments of “green” metals such as copper, nickel, cobalt and lithium.

In our latest Regional Economic Outlook, we explore the policy options available to maximize these opportunities. What combination of policies work best will depend on the challenges and circumstances of each country.

Policy options for climate mitigation

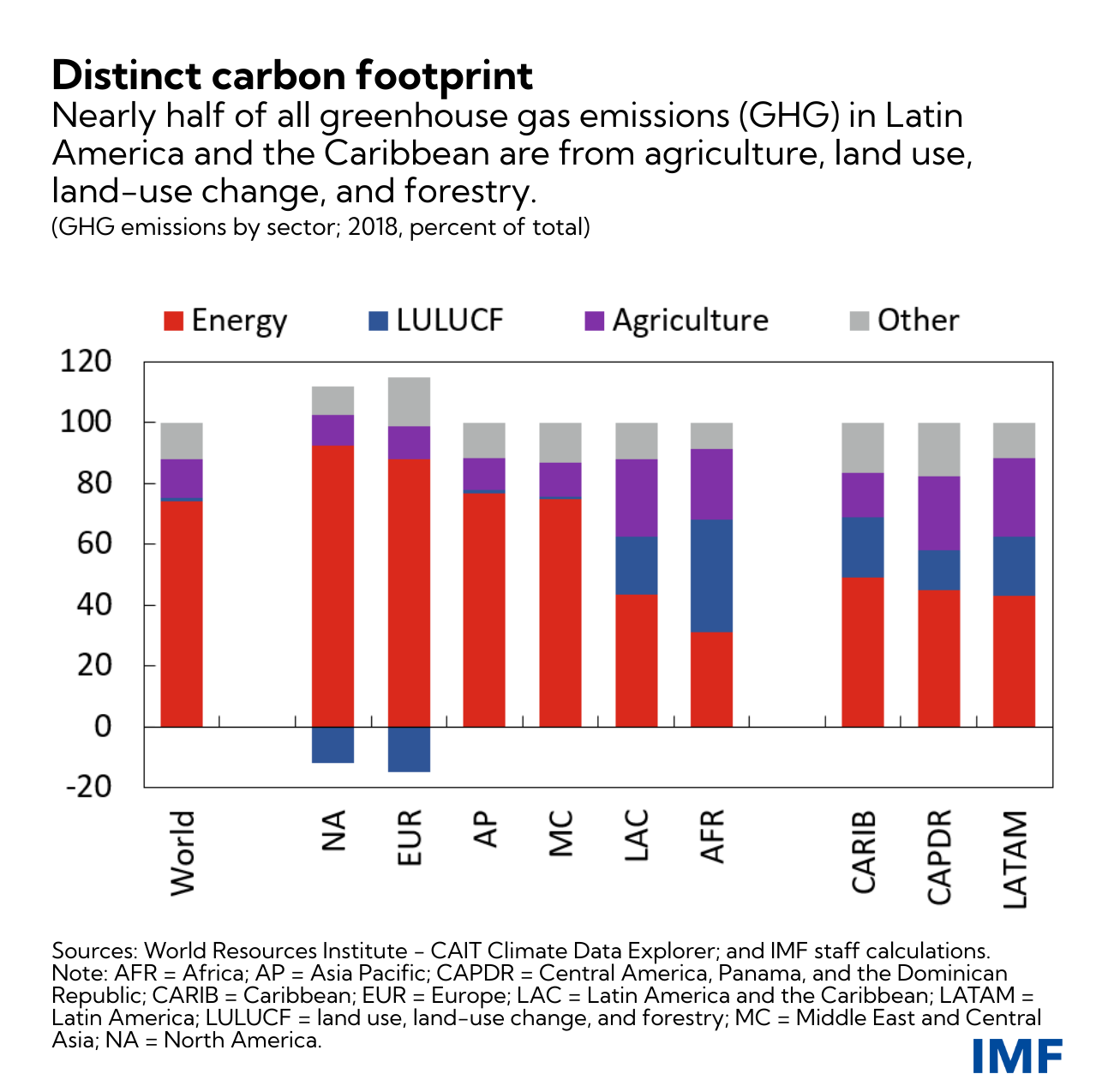

The region’s net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are in line with its economic size and population—about 8 percent of the global total. But the composition of emissions in LAC is very different from other regions.

The energy sector contributes much less to total emissions in LAC (43 percent) than the global average (74 percent). Agriculture, on the other hand, contributes 25 percent, compared to a global average of 13 percent. Land use, land-use change, and forestry (LULUCF) contributes 19 percent—vastly more than the global average of just over 1 percent.

Given the region’s large share of emissions from LULUCF as well as its many unique ecosystems and species, the region has the potential to reduce net emissions cost-effectively. In fact, model simulations in Huppmann et al. suggest that it may be more cost-effective for the world to compensate LAC countries for protecting, managing and restoring ecosystems than to devote the same resources to scaling up mitigation efforts elsewhere.

Policymakers in the region will need to adopt a multi-pronged approach to reach their climate change mitigation goals, focused on increasing energy efficiency and renewable energy use, reducing emissions in transportation and agriculture, and restoring and protecting forests (which act as natural carbon sinks).

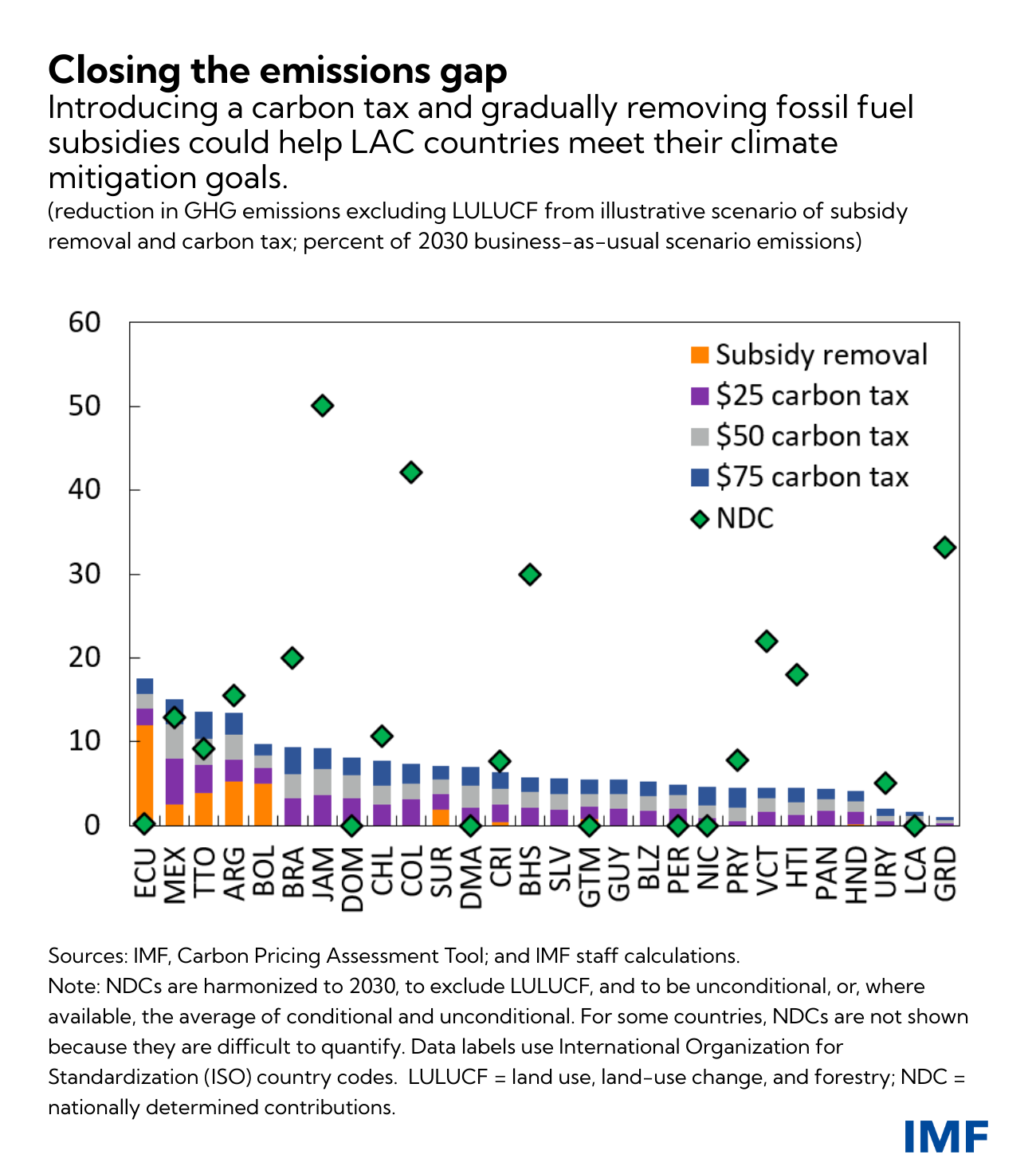

A policy toolkit for reaching these climate mitigation goals could include (i) price-based mitigation measures such as reduction in fossil fuel subsidies, introduction of carbon taxes, establishment of emissions trading systems, or development of a system of feebates; and (ii) non-price-based mitigation measures such as public investment in low-carbon technologies and infrastructure, fiscal incentives, and supportive regulations.

A gradual removal of energy subsidies and an introduction of universal carbon taxes of up to $75 per ton could help some countries in LAC reach their 2016 Paris accord targets. The revenues generated from these policies range between ½ and 4½ percent of GDP and could be used to compensate vulnerable households for higher carbon prices. In fact, our analysis indicates that universal cash transfers can fully offset the negative impact on the first six to seven deciles of per capita household consumption in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico.

Strengthening adaptation

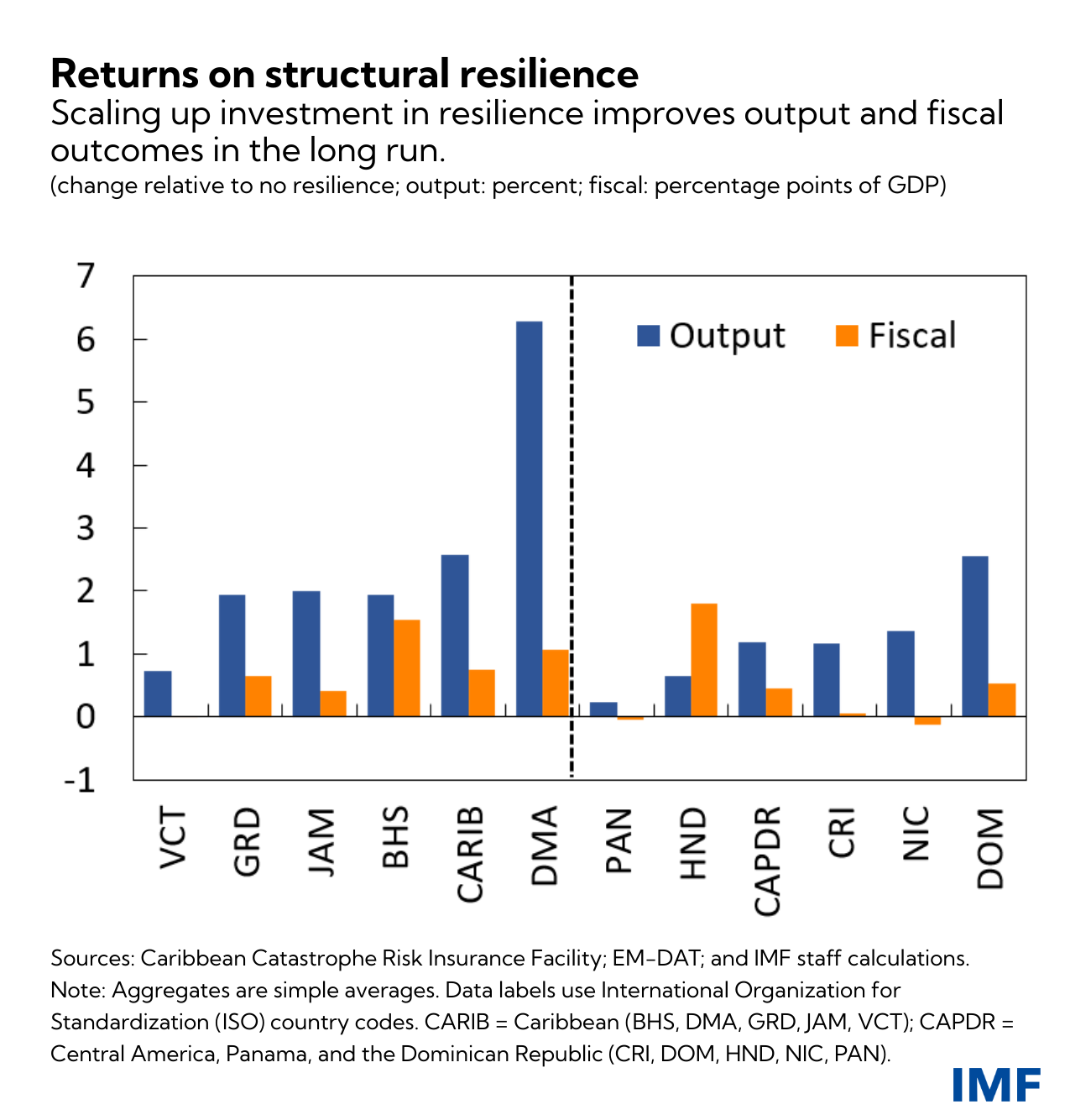

Climate-related disasters can cost billions. Reducing the economic costs will require substantial investments in resilience-building, particularly in infrastructure. We estimate that investing in structural resilience can boost the level of GDP in the long run between 2 and 6 percent for Caribbean islands and between 0.2 and 1.4 percent for Central American countries. Moreover, the level of output would be around ¼ percent higher three years after a natural disaster in the Caribbean on average and around 0.1 percent higher for Central American countries, once resiliency is achieved. The level of public debt would be ¾ percentage point lower after three years in the Caribbean and around ¼ percentage point lower in Central America.

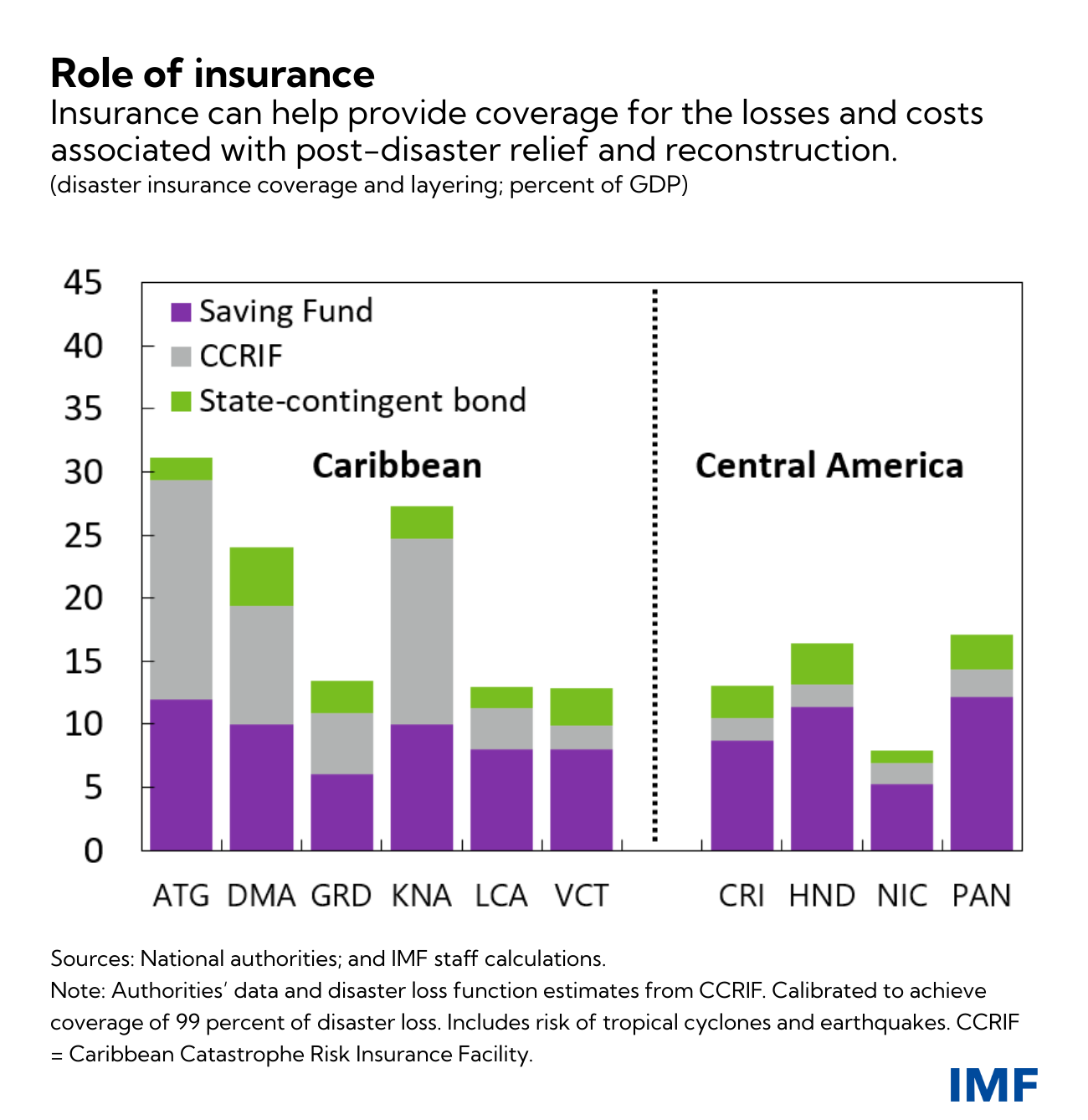

But because building structural resilience takes time, countries may also need to boost their financial resilience through insurance coverage. We estimate that insurance coverage of 15–30 percent of GDP for Caribbean countries and 10–20 percent of GDP for Central America, Panama, and the Dominican Republic could cover 99 percent of the fiscal costs related to natural disasters. This calculation is based on an insurance framework that includes building a precautionary government savings fund, accessing the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility and issuing state contingent bonds. This could cost countries between 0.5–2 percent of GDP per year.

Countries will need to be innovative in how they fund the upfront costs of resilience. Deeper private sector contributions to adaptation investment could help and can be facilitated by policies to improve access to financial services and the climate risk resilience of country financial systems.

The cost

Reaching LAC countries’ climate mitigation and adaptation goals will cost an estimated $90–110 billion per year for the entire region. These estimates are subject to a high degree of uncertainty. Nonetheless, as most countries will not be able to cover these costs, external financing—from both official and private sectors—will be essential.

On the private sector side, sustainability-linked debt and equity markets have the potential to support climate mitigation and adaptation efforts, but actions need to be taken to avoid “greenwashing”. State-contingent instruments, such as catastrophe bonds or debt-for-nature swaps, could also play a role. Private sector financing, however, will not be sufficient and bilateral and multilateral support—on concessional terms and in the form of grants for the most vulnerable countries—will be crucial.