The international tax system—shaped by the League of Nations in April 1923—has come under intense pressure in recent years. Globalization, digitalization, and tax competition have made it increasingly hard for countries to raise revenue from multinational companies in an effective, fair, and efficient manner. Following a decade of debate, 138 countries recently agreed to the first major overhaul of the international tax system in a century.

Our new IMF paper assesses the reform and finds that it is a major step in the right direction. But to reap its benefits countries need to implement it, with the optimal policy response depending on each country’s circumstances. Our paper argues that other reform efforts—both international and domestic—should continue, not least so that poorer countries can raise more revenue to meet their development needs.

The reform in a nutshell

The reform was agreed in 2021 by the members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development/Group of Twenty Inclusive Framework—a body with now 142 members tasked to address international tax avoidance by multinational companies and deal with the tax challenges arising from digitalization of the economy. The reform contains two pillars:

- Pillar 1 includes a new method to allocate profits to countries where

multinational companies may have significant business but few (or no) local

operations. This is increasingly common when firms sell through digital

channels. Under the existing system, countries have no right to tax such

profits in the absence of a physical establishment such as a warehouse or

factory on their territory.

- Pillar 2 introduces a global minimum effective tax rate of 15 percent. This is enforced through a set of top-up tax rules. For instance, if a country where operations take place levies taxes below this minimum, then the country where the corporate headquarters are located can collect additional taxes to reach the minimum rate.

Key achievements

The reform breaks with century-old norms. The move toward taxing profits in the destination country—that is, where final consumers are located—marks a paradigm shift, rendering the system more robust to tax base erosion since consumers are less mobile than intangible capital such as patents or technology. Moreover, the simplified allocation of profits by a formula reduces scope for aggressive tax planning. This currently occurs, for instance, when multinational companies manipulate transfer prices of transactions between group entities to shift profits to lower-tax countries—eroding countries’ tax bases and creating tax competition pressures.

The new minimum tax in Pillar 2 addresses this race to the bottom by putting a global floor on rates and raising the prospect of ending the decadelong downward trend in corporate tax rates. It also cuts back on profit shifting into investment hubs. The reduced pressure to compete, including through tax incentives, enables countries to design better domestic policies. Our paper shows that these indirect effects indeed might well yield bigger gains in revenue than the estimates of the direct impact of the reform suggest.

More work to be done

The reform initially has limited coverage. It covers only the largest multinational companies—and in case of Pillar 1, just over 100 firms. Under both pillars, relatively large chunks of profits are excluded. The reform is therefore unlikely to be the end point of change for the international tax system, although there are political and practical advantages to phasing in such a major overhaul.

The reform is still quite complex, creating implementation challenges especially for developing countries. Further simplification will be needed, with work currently under way in areas important to this group of economies, such as simplified approaches to taxing routine marketing and distribution operations.

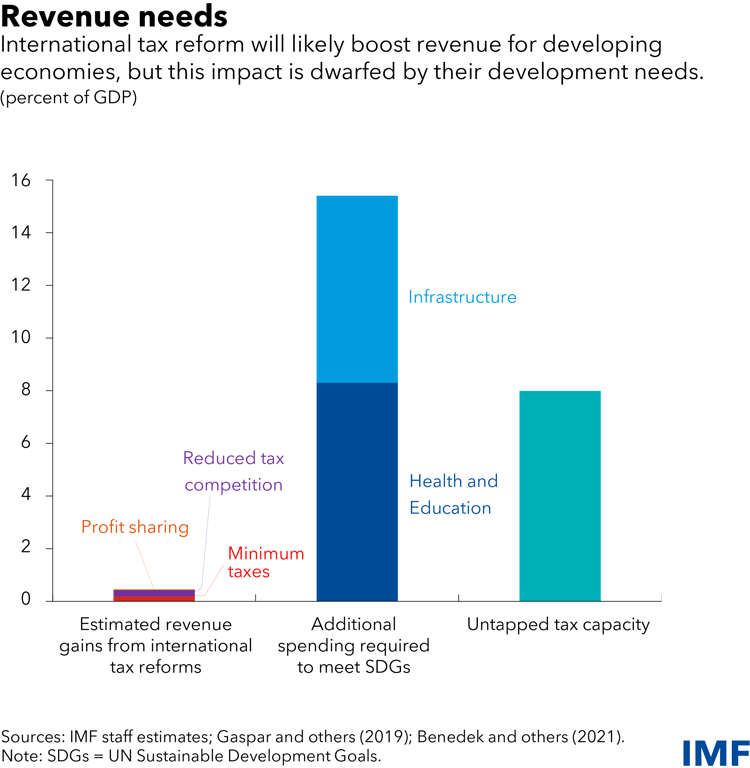

The additional revenue raised by the reform is welcome, but small (at initially just 0.2 percent of global gross domestic product). Low-income countries that wish to tackle their development needs will therefore need to raise domestic taxes and should not just rely on expected revenue from international tax agreements. We estimate that the reform will boost global revenue by just under 0.2 percent of GDP initially, although reduced tax competition might double the gains in the future.

These estimated revenue gains are nowhere near what developing countries need to meet the sustainable development goals. At the same time, we see the potential for low-income countries to increase their tax revenues by as much as 8 percent of GDP through domestic tax increases, based on estimates of their tax capacity—that is, the amount of tax they could raise based on their economic and demographic characteristics.

One option would be to use the scope created by reduced pressures for low tax rates and tax incentives and introduce a corporate tax system with fewer loopholes. Governments could also consider collecting more from other major taxes—such as the value-added tax, where there is significant untapped potential in many countries. They must also invest urgently in revenue administration—both to reap the full benefits of the reform and to support tax collection more generally.

The global tax agreement is an important step in the right direction, but it is not yet operational. While monitoring and evaluation are critical and further reforms likely, the most important next step is for countries to implement it swiftly.