World Economic Outlook

Restoring Confidence without Harming Recovery

July 2010

[$token_name="PublicationDisclaimer"]

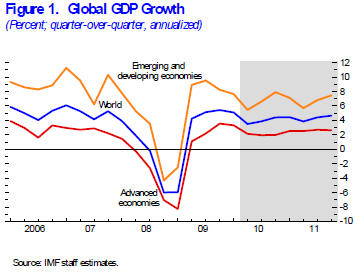

World growth is projected at about 4½ percent in 2010 and 4¼ percent in 2011. Relative to the April 2010 World Economic Outlook (WEO), this represents an upward revision of about ½ percentage point in 2010, reflecting stronger activity during the first half of the year. The forecast for 2011 is unchanged (Table 1; Figure 1: CSV|PDF). At the same time, downside risks have risen sharply amid renewed financial turbulence. In this context, the new forecasts hinge on implementation of policies to rebuild confidence and stability, particularly in the euro area. More generally, policy efforts in advanced economies should focus on credible fiscal consolidation, notably measures that enhance medium-run growth prospects, such as reforms to entitlement and tax systems. Supported by accommodative monetary conditions, fiscal actions should be complemented by financial sector reform and structural reforms to enhance growth and competitiveness. Policies in emerging economies should also help rebalance global demand, including through structural reforms and, in some cases, greater exchange rate flexibility.

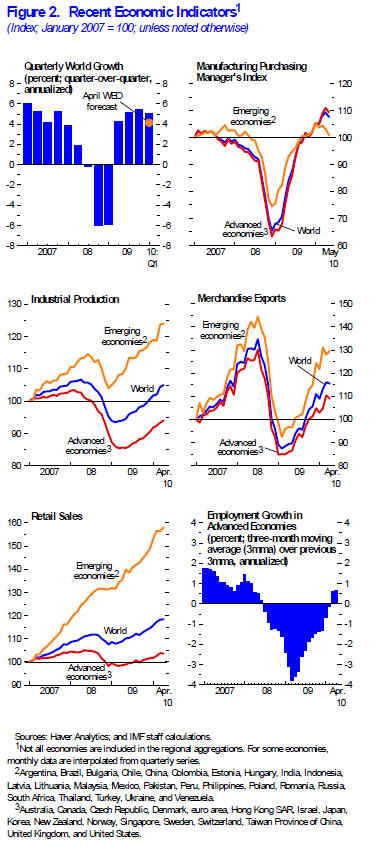

A strengthening global economy is battered by financial shocks

The world economy expanded at an annualized rate of over 5 percent during the first quarter of 2010. This was better than expected in the April 2010 WEO, mostly due to robust growth in Asia. More broadly, there were encouraging signs of growth in private demand. Global indicators of real economic activity were strong through April and stabilized at a high level in May. Industrial production and trade posted double-digit growth, consumer confidence continued to improve, and employment growth resumed in advanced economies (Figure 2: CSV|PDF). Overall, macroeconomic developments during much of the spring confirmed expectations of a modest but steady recovery in most advanced economies and strong growth in many emerging and developing economies.

Nevertheless, recent turbulence in financial markets—reflecting a drop in confidence about fiscal sustainability, policy responses, and future growth prospects—has cast a cloud over the outlook. Crucially, fiscal sustainability issues in advanced economies came to the fore during May, fuelled by initial concerns over fiscal positions and competitiveness in Greece and other vulnerable euro area economies.

Table 1. Overview of the World Economic Outlook Projections

(Percent change, unless otherwise noted)

| Year over Year | Q4 over Q4 | |||||||||||

| Projections | Difference from April 2010 WEO Projections |

Estimates | Projections | |||||||||

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | ||||

|

World Output1 |

3.0 | –0.6 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 4.2 | 4.3 | |||

|

Advanced Economies |

0.5 | –3.2 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | –0.5 | 2.3 | 2.6 | |||

|

United States |

0.4 | –2.4 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 3.2 | 2.6 | |||

|

Euro Area |

0.6 | –4.1 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 0.0 | –0.2 | –2.1 | 1.1 | 1.6 | |||

|

Germany |

1.2 | –4.9 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.2 | –0.1 | –2.2 | 1.3 | 1.7 | |||

|

France |

0.1 | –2.5 | 1.4 | 1.6 | –0.1 | –0.2 | –0.4 | 1.5 | 1.7 | |||

|

Italy |

–1.3 | –5.0 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.1 | –0.1 | –2.8 | 1.1 | 1.3 | |||

|

Spain |

0.9 | –3.6 | –0.4 | 0.6 | 0.0 | –0.3 | –3.1 | –0.1 | 1.2 | |||

|

Japan |

–1.2 | –5.2 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 0.5 | –0.2 | –1.4 | 1.1 | 3.0 | |||

|

United Kingdom |

0.5 | –4.9 | 1.2 | 2.1 | –0.1 | –0.4 | –3.1 | 2.1 | 1.9 | |||

|

Canada |

0.5 | –2.5 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 0.5 | –0.4 | –1.1 | 4.0 | 2.6 | |||

|

Other Advanced Economies |

1.7 | –1.2 | 4.6 | 3.7 | 0.9 | –0.2 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 4.6 | |||

|

Newly Industrialized Asian Economies |

1.8 | –0.9 | 6.7 | 4.7 | 1.5 | –0.2 | 6.1 | 4.3 | 6.3 | |||

|

Emerging and Developing Economies2 |

6.1 | 2.5 | 6.8 | 6.4 | 0.5 | –0.1 | 5.7 | 6.9 | 6.8 | |||

|

Central and Eastern Europe |

3.1 | –3.6 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 3.5 | |||

|

Commonwealth of Independent States |

5.5 | –6.6 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 0.3 | 0.7 | ... | ... | ... | |||

|

Russia |

5.6 | –7.9 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 0.3 | 0.8 | –3.8 | 3.7 | 3.9 | |||

|

Excluding Russia |

5.3 | –3.4 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 0.5 | 0.2 | ... | ... | ... | |||

|

Developing Asia |

7.7 | 6.9 | 9.2 | 8.5 | 0.5 | –0.2 | 9.8 | 9.0 | 8.7 | |||

|

China |

9.6 | 9.1 | 10.5 | 9.6 | 0.5 | –0.3 | 12.1 | 9.8 | 9.6 | |||

|

India |

6.4 | 5.7 | 9.4 | 8.4 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 7.3 | 10.3 | 8.0 | |||

|

ASEAN-53 |

4.7 | 1.7 | 6.4 | 5.5 | 1.0 | –0.1 | 5.1 | 4.9 | 6.8 | |||

|

Middle East and North Africa |

5.3 | 2.4 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 0.0 | 0.1 | ... | ... | ... | |||

|

Sub-Saharan Africa |

5.6 | 2.2 | 5.0 | 5.9 | 0.3 | 0.0 | ... | ... | ... | |||

|

Western Hemisphere |

4.2 | –1.8 | 4.8 | 4.0 | 0.8 | 0.0 | ... | ... | ... | |||

|

Brazil |

5.1 | –0.2 | 7.1 | 4.2 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 4.4 | 5.3 | 4.3 | |||

|

Mexico |

1.5 | –6.5 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 0.3 | –0.1 | –2.4 | 3.5 | 4.3 | |||

|

Memorandum |

||||||||||||

|

European Union |

0.9 | –4.1 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 0.0 | –0.2 | –2.2 | 1.3 | 1.7 | |||

|

World Growth Based on Market Exchange Rates |

1.8 | –2.0 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 0.4 | 0.0 | ... | ... | ... | |||

|

World Trade Volume (goods and services) |

2.8 | –11.3 | 9.0 | 6.3 | 2.0 | 0.2 | ... | ... | ... | |||

|

Imports |

||||||||||||

|

Advanced Economies |

0.5 | –12.9 | 7.2 | 4.6 | 1.8 | 0.0 | ... | ... | ... | |||

|

Emerging and Developing Economies |

8.6 | –8.3 | 12.5 | 9.3 | 2.8 | 1.1 | ... | ... | ... | |||

|

Exports |

||||||||||||

|

Advanced Economies |

1.8 | –12.6 | 8.2 | 5.0 | 1.6 | 0.0 | ... | ... | ... | |||

|

Emerging and Developing Economies |

4.5 | –8.5 | 10.5 | 9.0 | 2.2 | 0.6 | ... | ... | ... | |||

|

Commodity Prices (U.S. dollars) |

||||||||||||

|

Oil4 |

36.4 | –36.3 | 21.8 | 3.0 | –7.7 | –0.8 | ... | ... | ... | |||

|

Nonfuel (average based on world commodity export weights) |

7.5 | –18.7 | 15.5 | –1.4 | 1.6 | –0.9 | ... | ... | ... | |||

|

Consumer Prices |

||||||||||||

|

Advanced Economies |

3.4 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 1.3 | –0.1 | –0.1 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.5 | |||

|

Emerging and Developing Economies2 |

9.3 | 5.2 | 6.3 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 4.9 | 6.1 | 4.1 | |||

|

London Interbank Offered Rate (percent)5 |

||||||||||||

|

On U.S. Dollar Deposits |

3.0 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.1 | –0.8 | ... | ... | ... | |||

|

On Euro Deposits |

4.6 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.2 | –0.1 | –0.4 | ... | ... | ... | |||

|

On Japanese Yen Deposits |

1.0 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 | –0.1 | –0.1 | ... | ... | ... | |||

|

Note: Real effective exchange rates are assumed to remain constant at the levels prevailing during April 29–May 27, 2010. Country weights used to construct aggregate growth rates for groups of economies were revised. When economies are not listed alphabetically, they are ordered on the basis of economic size. The aggregated quarterly data are seasonally adjusted. | ||||||||||||

|

1The quarterly estimates and projections account for 90 percent of the world purchasing-power-parity weights. | ||||||||||||

|

2The quarterly estimates and projections account for approximately 79 percent of the emerging and developing economies. | ||||||||||||

|

3Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. | ||||||||||||

|

4Simple average of prices of U.K. Brent, Dubai, and West Texas Intermediate crude oil. The average price of oil in U.S. dollars a barrel was $61.78 in 2009; the assumed price based on future markets is $75.27 in 2010 and $77.50 in 2011. | ||||||||||||

|

5Six-month rate for the United States and Japan. Three-month rate for the Euro Area. | ||||||||||||

Concern over sovereign risk spilled over to banking sectors in Europe. Funding pressure reemerged and spread through interbank markets, fed also by uncertainty about policy responses. At the same time, questions about sustainability of the strength of the global recovery surfaced.

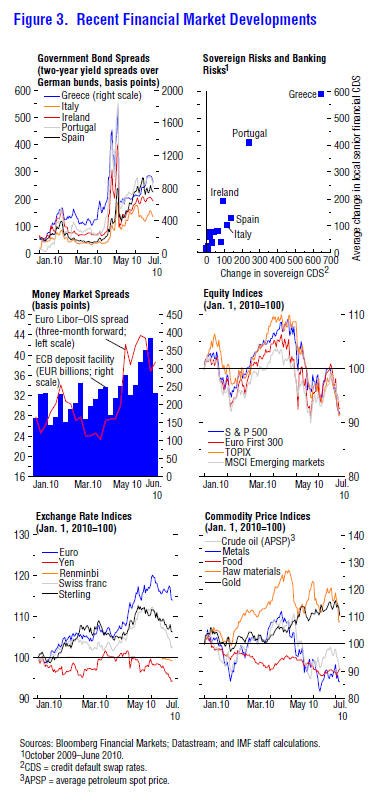

As risk appetite waned and markets scaled back expectations for future growth, assets in other regions, including emerging markets, also experienced substantial sell-offs. This spilled over into sharp movements in currency, equity, and commodity markets (Figure 3: CSV|PDF).

In principle, the renewed financial turbulence could spill over to the real economy through several channels, involving changes in domestic and external demand and in relative exchange rates. The supply of bank credit could be curtailed by heightened uncertainty about financial sector exposure to sovereign risk as well as increased funding costs, notably in Europe. Moreover, lower consumer and business confidence could suppress private consumption and investment. Fiscal consolidation could also dampen domestic demand. To the extent that higher risk premiums were accompanied by depreciation of the euro, the latter would boost net exports and mitigate the overall negative effect on growth in Europe. However, the negative growth spillovers to other countries and regions could be substantial because of financial and trade linkages. Lower risk appetite could initially reduce capital flows to emerging and developing economies. But relatively more robust growth prospects and low public debt could eventually result in higher capital flows, as some emerging market economies become a more attractive investment destination than some advanced economies.

Global recovery will continue, despite more financial turbulence

At this juncture, the potential dampening effect on growth of recent financial stress is highly uncertain. So far, there is little evidence of negative spillovers to real activity at a global level. Hence, the projections below incorporate a modest negative effect on growth in the euro area. The euro area projections also hinge on the use, as needed, of the new European Stabilization Mechanism (aimed at preserving financial stability) and, more important, on successful implementation of well-coordinated policies to rebuild confidence in the banking system. As a result, financial market conditions in the euro area are assumed to stabilize and improve gradually. The additional fiscal consolidation triggered by the financial turmoil (of about ½ percent of GDP) is projected to detract from euro area growth in 2011 (about ¼ percentage point relative to the April 2010 WEO), whereas the negative impact of tighter financing conditions will be countered by the positive effects of euro depreciation.

Contagion to other regions is assumed to be limited and the disruption in capital flows to emerging and developing economies to be temporary. But there is a downside scenario: further deterioration in financial conditions could have a much greater adverse effect on global growth as a result of cross-country spillovers through financial and trade channels.

Overall, output in advanced economies is now expected to expand by 2½ percent in 2010, a small upward revision of ¼ percentage point, due mostly to stronger-than-expected growth during the first quarter, especially in advanced economies in Asia. Indeed, on a Q4-over-Q4 basis, the forecast is broadly unchanged at 2¼ percent, implying lower growth during the second half of 2010 on account of the financial turbulence.

For 2011, growth in advanced economies remains broadly unchanged from the April 2010 WEO, at 2½ percent. Somewhat stronger projected growth in the United States (owing to gathering momentum in private demand) is offset by slightly weaker projected growth in the euro area (due to the turbulence). Overall, the WEO forecast continues to be consistent with a modest recovery in advanced economies, albeit with substantial differentiation among them. Challenging the recovery in these economies are high levels of public debt, unemployment, and in some cases, constrained bank lending.

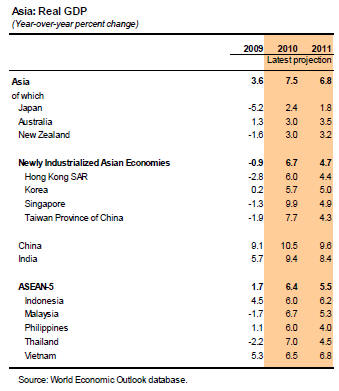

For 2011, output growth in emerging and developing economies is expected to edge down to 6½ percent on an annual basis. This forecast is broadly unchanged from the April 2010 WEO. However, growth is now projected at 6¾ percent on a Q4-over-Q4 basis, which represents a downward revision of ½ percentage point. The projections are consistent with still-robust growth overall in emerging and developing economies, but with considerable diversity among them. Key emerging economies in Asia (Box 1: PDF) and in Latin America continue to lead the recovery. Given the relatively modest effects to date of the financial turbulence on euro area growth and on commodity prices, growth prospects remain favorable for many developing countries in sub-Saharan Africa as well as for commodity producers in all regions. Nimble policy responses and stronger economic frameworks are helping many emerging economies rev up internal demand and attract capital flows. The ongoing rebound in global trade is also supporting the recovery in many emerging and developing economies.

Inflation to remain mostly subdued

Prices of many commodities fell during the financial market shocks in May and early June, reflecting in part expectations for weakened global demand. Prices recovered some ground more recently, as concern about the real spillovers of the financial turbulence has eased. At the same time, waning appetite for risk prompted gold prices to settle higher. In line with futures market developments, the IMF’s baseline petroleum price projection has been revised down to $75.3 a barrel for 2010 and $77.5 a barrel for 2011 (from $80 and $83, respectively, in the April 2010 WEO). Projections for the nonfuel commodity price index have remained broadly unchanged, partly reflecting stronger-than-expected market conditions through April.

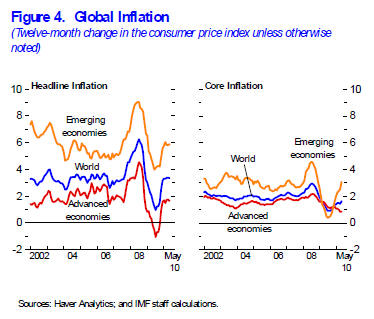

Inflation pressures are expected to remain subdued in advanced economies (Figure 4: CSV|PDF). The still-low levels of capacity utilization and well-anchored inflation expectations should contain inflation pressures in advanced economies, where headline inflation is expected to remain around 1¼-1½ percent in 2010 and 2011. In a number of advanced economies, the risks of deflation remain pertinent in light of the relatively weak outlook for growth and the persistence of considerable economic slack.

In contrast, in emerging and developing economies, inflation is expected to edge up to 6¼ percent in 2010 before subsiding to 5 percent in 2011.

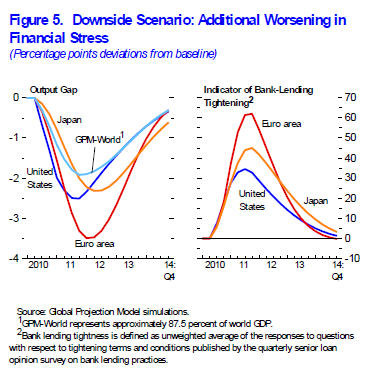

Downside risks to global growth are much greater

Downside risks have risen sharply. In the near term, the main risk is an escalation of financial stress and contagion, prompted by rising concern over sovereign risk. This could lead to additional increases in funding costs and weaker bank balance sheets and hence to tighter lending conditions, declining business and consumer confidence, and abrupt changes in relative exchange rates. Given trade and financial linkages, the ultimate effect could be substantially lower global demand. To illustrate the likely growth effects, Figure 5 (CSV|PDF) presents an alternative scenario using the IMF’s Global Projection Model (GPM). The scenario assumes that the magnitude of shocks to financial conditions and domestic demand in the euro area are as large as those experienced in 2008. The model simulation also incorporates significant contagion to financial markets, particularly in the United States, where reductions in equity prices dampen private consumption. Given negative financial and trade spillovers, growth is suppressed in other regions as well. In this downside scenario, world growth in 2011 is reduced by about 1½ percentage points relative to the baseline.

In addition, growth prospects in advanced economies could suffer if an overly severe or poorly planned fiscal consolidation stifles still-weak domestic demand. There are also risks stemming from uncertainty about regulatory reforms and their potential impact on bank lending and economy-wide activity. Yet another downside risk is the possibility of renewed weakness in the U.S. property market. These downside risks to growth in advanced economies also complicate macroeconomic management in some of the larger, fast-growing economies in emerging Asia and Latin America, which face some risk of overheating.

Daunting policy challenges lie ahead

Against this uncertain backdrop, the overarching policy challenge is to restore financial market confidence without choking the recovery.

In the euro area, well-coordinated policies to rebuild confidence are particularly important. As discussed in the July 2010 Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR) Update, immediate priorities in the financial sphere include: making the new European Stabilization Mechanism fully operational, resolving uncertainty about bank exposures (including to sovereign debt), ensuring that European banks have adequate capital buffers, and continuing liquidity support.

At a global level, policies should focus on implementing credible plans to lower fiscal deficits over the medium term while maintaining supportive monetary conditions, accelerating financial sector reform, and rebalancing global demand.

“Growth-friendly” medium-term fiscal consolidation plans are urgently needed

Of utmost importance are firm commitments to ambitious and credible strategies to lower fiscal deficits over the medium and long term. Such plans could include legislation creating binding multiyear targets and should emphasize policy measures that reform pension entitlements and public health care systems, make permanent reductions in non-entitlement spending, improve tax structures, and strengthen fiscal institutions. Such steps should mitigate the type of adverse short-term effects on domestic demand that fiscal consolidation has commonly caused in the past by reducing the fiscal burden for the future and boosting the economy’s supply potential.

In the near term, the extent and type of fiscal adjustment should depend on country circumstances, particularly the pace of recovery and the risk of a loss of fiscal credibility, which can be mitigated by the adoption of credible medium-term consolidation plans.

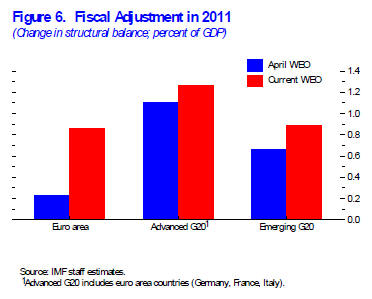

Most advanced economies do not need to tighten before 2011, because tightening sooner could undermine the fledgling recovery, but they should not add further stimulus. Current fiscal consolidation plans for 2011, which envisage a fiscal retrenchment corresponding to an average change in the structural balance of 1¼ percentage points of GDP, are broadly appropriate (Figure 6: CSV|PDF).

Economies facing sovereign funding pressures have already had to embark on immediate fiscal consolidation; in these economies, strong signals of commitment through politically-difficult, upfront measures are necessary. More generally, countries that are unable to credibly commit to medium-term consolidation may find themselves compelled by adverse market reactions to undertake more frontloaded adjustments.

Meanwhile, fast-growing advanced and emerging economies can start to tighten now. For some, it may be preferable to use fiscal policy rather than monetary policy to contain demand pressures if tighter monetary conditions could exacerbate pressure from capital inflows. In contrast, in economies with excessive external surpluses and relatively low public debt, fiscal tightening should take a backseat to monetary tightening and exchange rate adjustment, in order to facilitate the necessary rebalancing toward domestic demand.

Monetary and exchange rate policies should support global demand rebalancing

Monetary policy remains an important policy lever. Given subdued inflation pressures, monetary conditions can remain highly accommodative for the foreseeable future in most advanced economies. This will help mitigate the adverse effects on growth of earlier and larger fiscal consolidations as well as of financial market jitters. Moreover, if downside risks to growth materialize, monetary policy should be the first line of defense in many advanced economies. In such a scenario, with policy interest rates already near zero in several major economies, central banks may need to again rely more strongly on using their balance sheets to further ease monetary conditions.

Monetary policy requirements are more diverse for emerging and developing economies. Some of the larger, fast-growing emerging economies, faced with rising inflation or asset price pressures, have appropriately tightened monetary conditions, and markets are pricing in further moves. But monetary policy actions must remain responsive in both directions. In particular, should downside risks to global growth materialize, there may need to be a swift policy reversal.

In emerging economies with excessive external surpluses, monetary tightening should be supported with nominal effective exchange rate appreciation as excess demand pressures build, including in response to continued fiscal support to facilitate demand rebalancing or renewed capital flows. In this context, any concerns about exchange rate overshooting could be addressed by fiscal tightening to ease pressure on interest rates, by some buildup of reserves, by macroprudential measures, and possibly by stricter controls on capital inflows—mindful of the potential to create new distortions—or looser controls on outflows.

Financial system reform needs to be accelerated

Recently renewed financial strains underscore the urgent need to reform financial systems and restore the health of banking systems. In many advanced economies, more progress is needed on bank recapitalization; bank consolidation, resolution, and restructuring; and regulatory reform. In some cases, larger capital buffers are required to absorb the ongoing and potential future deterioration in credit quality and to meet expected higher capital standards. In the absence of complete banking sector recapitalization and restructuring, the flow of credit to the economy will continue to be impaired. As discussed in the July 2010 GFSR Update, bank funding remains a concern, given upcoming debt rollovers.

Greater transparency is also a priority. Resolving uncertainty about bank exposures, including to sovereign debt, could alleviate pressure in the European interbank markets and help improve market sentiment. As discussed in the July 2010 GFSR Update, publishing the results of the ongoing stress tests in Europe is a step in the right direction. But this should be complemented by credible plans to strengthen capital levels as needed and by further efforts to increase the transparency of the activities of European financial institutions that are not publicly traded and do not publish quarterly accounts.

There is also a pressing need to reduce ongoing uncertainty about the regulatory environment and to implement long-awaited reforms. Otherwise, policy opacity could hinder banks’ willingness to supply credit and support the recovery. Hence, credible and consistent plans and timetables for implementing regulatory reform need to be developed and to reduce uncertainty. Unilateral measures should be avoided as they could have unintended consequences, especially if market confidence suffers.

Global demand rebalancing and key structural reforms are essential to support future growth

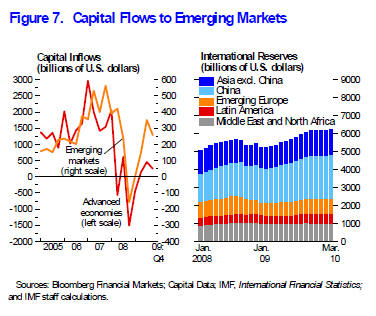

Last but not least, the ongoing rebalancing of global demand must be supported by bold policy action. To some extent, financial markets and capital flows are already facilitating global demand rebalancing through currency pressures, although many economies have been resisting them by building up reserves (Figure 7: CSV|PDF).

In economies with excessive external surpluses, the transition toward domestic sources of demand should continue, helped by structural policies to reform social safety nets and to improve productivity in the service sector as well as, in a variety of cases, more flexible exchange rates. In economies with excessive external deficits, fiscal consolidation and financial sector reform should help rebalance demand.

However, successful fiscal adjustment is difficult without strong growth. Structural reform, particularly in product and labor markets, is needed to raise potential growth and improve competitiveness, particularly in many economies facing large fiscal adjustment. Also, tax-reform efforts should give preference to measures that encourage investment, because such policies are less likely to dampen domestic demand in the near term.

In sum, ambitious and complementary policy efforts are needed to promote strong, sustainable, and balanced global growth over the medium term.