(Versions in Español and Português)

As the U.S. Federal Reserve prepares to raise policy rates for the first time in almost a decade, Latin America is in the midst of a sharp downturn with unemployment on the rise. In this context, many central banks across the region have kept interest rates low to support economic activity. But can monetary policy stay that way as global rates rise? What will the Fed liftoff imply for the region?

Our analysis in the Regional Economic Outlook: Western Hemisphere suggests the effects of the upcoming Fed rate increase should be manageable for the region, although local long-term rates could increase considerably if the U.S. term premium—the compensation sought by investors for potential losses due to interest rate or inflation risk—reverts to its precrisis average. Countries with flexible exchange rates and credible monetary and fiscal frameworks should be able to continue providing support by keeping short rates low where needed.

Following the Fed’s lead or simply dancing to the same tune?

In the early 2000s, many Latin American central banks adopted inflation targeting regimes featuring exchange rate flexibility, in part to avoid the need to deploy policies that exacerbated economic downturns triggered by large external shocks such as the Tequila and Asian crises of the 1990s. But some argue that because of financial globalization, policymakers in small open economies cannot run independent or autonomous monetary policies, even under flexible exchange rate regimes.

Indeed, interest rates around the world have tended to move in tandem, typically following U.S. rates. But global business cycles also tend to be highly synchronized, so the observed comovement in interest rates may reflect that central banks were reacting to similar conditions, rather than following the Fed. This distinction is particularly relevant in Latin America now, where many business cycles in the region are out of sync with the U.S. business cycle.

To answer this question, we decompose the movements in domestic interest rates of 46 advanced and emerging countries into two parts. The first component reflects the central bank’s efforts to stabilize output and inflation. The second is everything else, including other central bank objectives—such as moderating exchange rate movements due to financial stability or competitiveness concerns—or shocks that affect monetary conditions. We then ask to what extent this residual movement in domestic interest rates can be attributed to spillovers from global financial conditions, such as shifts in U.S. policy rates. The answer to this question will suggest how much monetary autonomy central banks really have.

We find that once we control for domestic macroeconomic conditions, spillovers from U.S. rates are smaller than simple interest rate correlations. But they are still significant for some emerging as well as advanced countries, suggesting they do follow the Fed. In Latin America, spillovers are significant and relatively large in Mexico and Peru, suggesting that, even if their economies were out of sync with that of the United States, they would be less likely to deviate from the Fed’s behavior.

The setting around the U.S. liftoff

But beyond what central banks can do to keep short-term rates in sync with domestic conditions, a lot of what may happen in the current juncture will depend on the nature of the factors driving U.S. interest rates—including, in particular, what happens to the term premium.

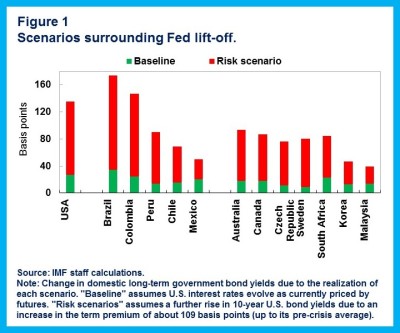

Figure 1 shows the estimated impact of Fed lift-off on long-term interest rates in selected countries after one year. Under the baseline scenario, U.S. rates increase according to current market expectations embedded in futures contracts. As the market is expecting a very gradual hiking cycle in line with an improving economic outlook, the impact is expected to be small across Latin America.

However, certain risk scenarios could cause larger impacts. For instance, the Fed could lift rates faster than markets currently expect. Alternatively, an unusually low term premium reflected in very low long-term U.S. interest rates could decompress. If this risk materializes, the impact on Latin American interest rates could be substantial—over 160 basis points in some cases—with important implications for government spending on debt service.

While these scenarios are considerably less likely than the baseline, they are not unprecedented. In the case of a term premium decompression back to its precrisis average, movements this size have been observed several times since 2000, including in the months following the “taper tantrum” episode of May 2013.

Flexible exchange rates and credible policy frameworks are key

An increase in domestic long-term rates may be unavoidable, but keeping shorter-term rates aligned with domestic conditions would certainly help. In that sense, our analysis suggests that the difference in spillovers across countries can be linked to policies and other characteristics (Figure 2). Exchange rate flexibility plays the key role in ensuring that the central bank can gear monetary policy to a greater degree towards stabilizing the domestic economy. But the strength of policy frameworks is also crucial. The credibility of the central bank’s commitment to price stability, as well as the market’s perception of fiscal vulnerabilities, are both important determinants of interest rate spillovers.

Other factors can also help. For instance, financial dollarization substantially increases interest-rate spillovers, while an active use of reserve requirements—one part of the macroprudential toolbox—can help mitigate them to some extent.