The poet Langston Hughes once asked, “What happens to a dream deferred?” It is a relevant question to millions around the world today, especially young people, because of inequality and poverty.

This week IMF staff are launching new, European Union-focused research highlighting the impact of unemployment and the long-term consequences of inadequate social protection on the young. The study also explores ideas that can help fix the problem and reduce inequality and poverty for the next generation.

Europe is certainly not the only region where young people face headwinds. However, the availability of data collected on age groups over the past decade means that we can take a closer look at Europe.

At first glance, inequality does not seem to be as big a threat in Europe as elsewhere. Average income inequality has remained broadly stable there since 2007. This is in large part thanks to strong social safety nets and redistribution, important achievements that have helped millions of people and strengthened Europe’s position compared to many other advanced economies.

Beneath the topline numbers, however, there is a worrying trend: the gap between generations in Europe has widened significantly. Working-age people, and especially the young, are falling behind.

Without action, a generation may never be able to recover.

How did we get here?

What has driven inequality across generations in Europe? While there are many dimensions to inequality—including wealth and gender—our study focuses first on income.

Incomes declined for young people after the 2007 crisis due to unemployment. They have since recovered, but have not grown. For those who are 65 years and older incomes increased by 10 percent as pensions were better protected.

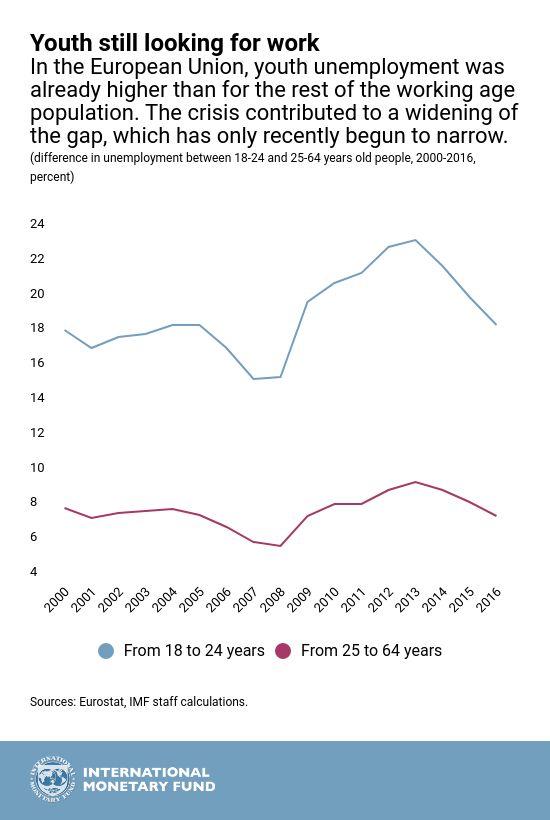

Looking at the job market, we can see where the problems developed. Youth unemployment started high and spiked to 24 percent in 2013. Today, nearly one in five young people in Europe are still looking for work.

IMF staff research shows that unemployment can lead to “scarring”: after long spells of unemployment and with limited experience, the young are less likely to find work. If they do find it, it will likely be at lower wages. Wages not earned and savings not put aside can be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to recover later in a person’s career.

Young people have the highest debt relative to their assets of any age group. This means that they are more vulnerable to financial shocks. In essence, they are putting their dreams on hold.

But incomes are only one part of the story: poverty is the other.

Lower income, more poverty

Before the global financial crisis, the relative poverty of young (18-24) and older people (65 +) in Europe was similar. But since the crisis, a major gap has developed. As a consequence, one in four young people in the region are at risk of poverty—living with incomes below 60 percent of the median.

It is not just unemployment that has brought us to this point. Underemployment became more prevalent following the crisis.

The rise of the so-called “gig” economy, and increases in temporary contracts, exacerbated the problem and further decreased job stability, particularly for the young. Unfortunately, as young people lost jobs or could only find part-time work, they were left without a sufficient safety net.

Inadequate social protection

In addition to these income and labor market issues, following the crisis, non-pension social benefits were often curtailed, and sometimes too narrowly targeted or not indexed to inflation. This limited the effectiveness of these programs for young people.

Just to be clear: programs such as pensions and social security have helped millions before and since the crisis. In particular, Europe’s senior citizens have been relatively well protected—which should continue to be the case, of course. But at the same time, we also need policies that pay more attention to the young and reflect the changing nature of work.

The good news is that some countries in Europe are already making progress.

In Germany, long-standing apprenticeships and training programs have helped the young stay in the workplace. Flexible employment rules allowed young people to keep their jobs during and after the crisis. Germany’s youth now have the lowest unemployment of any European Union country.

Another good example is Portugal, which exempted its first-time job holders from paying social security taxes for three years. While youth unemployment remains high, this measure goes in the right direction.

The next steps for the next generation

So, what should policymakers do? Our work offers some ideas that can help reduce inequality and poverty across generations in Europe.

- First, look at labor markets. To create jobs and incentivize work, policymakers can reduce social security contributions and taxes on low wage workers. To help improve future job prospects, governments can invest in education and training, which can help young people close the skills gap.

- Second, countries can make government spending on social protection more effective. How? Part of the answer is to adapt social spending, especially unemployment and other non-pension benefits, to ensure young people are better protected in the event of job loss.

- Third, taxes. Wealth taxes are lower today than in 1970. In some countries, more progressive tax systems and wealth taxes (including inheritance taxes) could help fund much-needed social programs for younger citizens.

Let me underline again: this is not about one age group versus another. Building an economy that works for young people creates a stronger foundation for everyone. Young people with productive careers can contribute to social safety nets. And reducing inequality across generations goes hand-in-hand with creating sustained growth and rebuilding trust within society.

None of this is easy. Policies need to be tailored to the needs of individual countries, recognize political realities, and stay within a budget.

But there is no doubt that now is the right moment to act — “the time to fix the roof is while the sun is shining.”

With stronger global growth, and the recovery in Europe, we have an opportunity to do the difficult things that otherwise might go undone. We can design policies that will enable the next generation to realize their potential. We can help heal the scars of the crisis, and we can ensure the next generation does not have to ask the question: “What happens to a dream deferred?”

You can also watch the video of my presentation from Davos