The Global Bank Stress Test is a major milestone in the IMF’s ability to gauge the impact of global shocks like the pandemic. Originally outlined in our October 2020 Global Financial Stability Report, it provides a first-of-its-kind assessment of potential shocks and spillovers to the world’s banks. And it’s also a useful new tool for central banks and financial regulators to consider the effects of global shocks on domestic systems.

The analysis in our new Departmental Paper on the global stress test includes a quarter century of bank-level data through 2020 for 257 of the largest lenders from across 24 advanced economies and five emerging markets. Together, the institutions account for 70 percent of the world’s banking assets. In each economy, the stress test covers as many institutions as necessary to account for at least 80 percent of assets for the individual banking systems.

This comprehensive sweep is important because bank stress tests are usually done at a national level by central banks and supervisory authorities, or across a currency union. That generally puts more focus on domestic risks than the total level of global resilience, and countries have different data and methodologies for evaluations that can make it challenging to compare scenarios and results from one country to another.

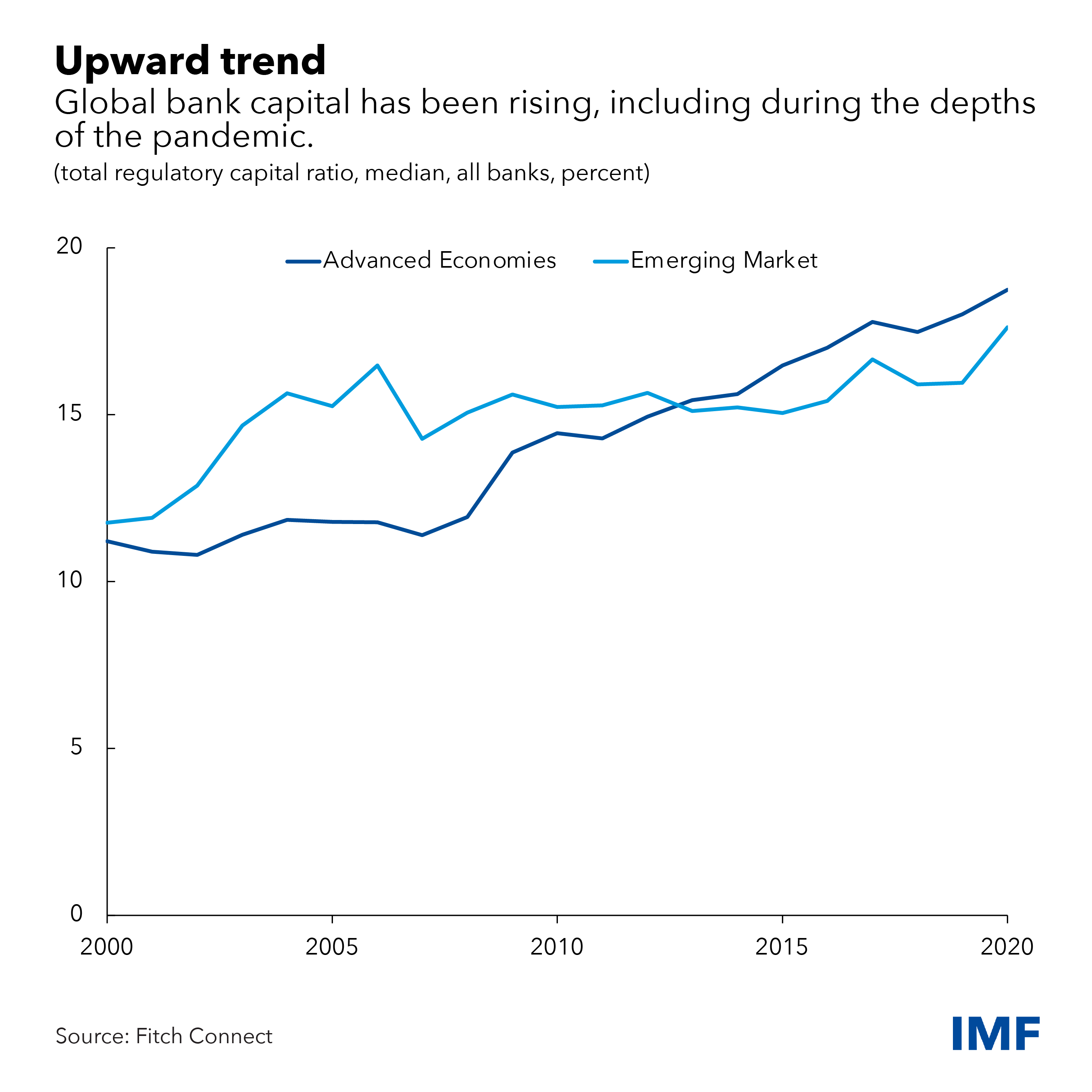

Banking systems have seen a trend of strengthening capital in the wake of reforms launched after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

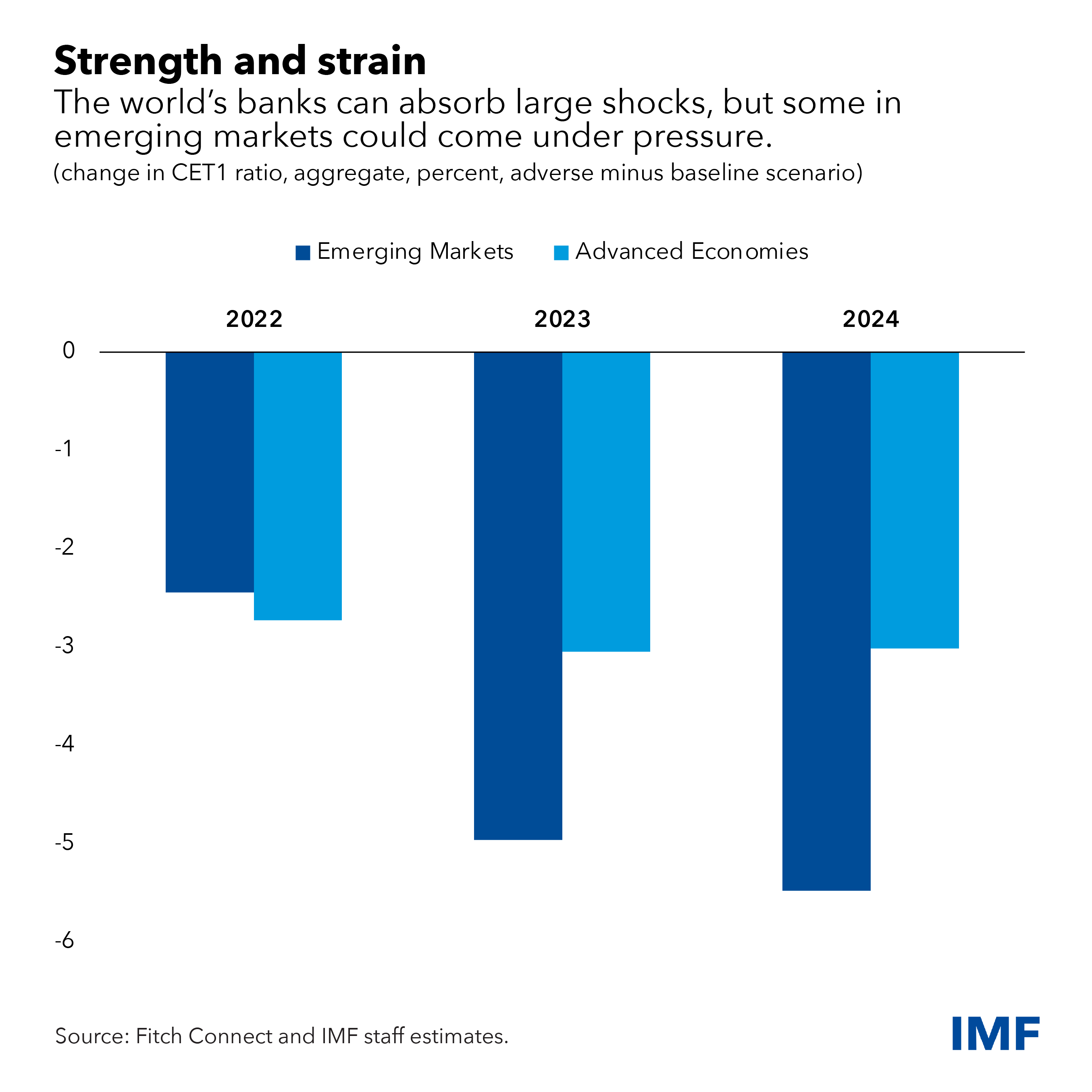

The Global Bank Stress Test results applied to scenarios, broadly in line with the pandemic shock in terms of impact on key macro variables, show an encouraging picture of resilience, but also a need for continued close monitoring. This is especially true in emerging economies that still have pockets of vulnerability combined with more constrained space for policies to respond to new challenges.

In the test’s adverse scenario, global gross domestic product was about 5 percentage points lower than our fall 2021 baseline assumptions for 2022, and 2.5 percentage points less for 2023. A sharper tightening in financial conditions for vulnerable businesses in emerging markets and developing economies results in a larger shock for those economies that also have a higher sensitivity of their core equity capital to shocks.

Banks in emerging markets face greater risks in an adverse scenario, reflecting the higher sensitivity of their core equity capital to shocks.

While this analysis predates the war in Ukraine and current concerns about stagflation, it suggests that banking systems remain able to absorb shocks from adverse developments in global growth and risk premia broadly in line with those seen during the pandemic, though there remain uncertainties associated with the evolution of capital levels during 2021 and the policy space to absorb new shocks.

— This blog also reflects research contributions from departmental paper co-authors Xiaodan Ding, Marco Gross, Dimitrios Laliotis, Fabian Lipinsky, Pavel Lukyantsau, and Thierry Tressel