September 21, 2017

Versions in Español (Spanish) Português (Portuguese)

[caption id="attachment_21311" align="alignnone" width="1024"] Systemic corruption drains public resources and drags down economic growth (photo: People Images/iStock).[/caption]

Systemic corruption drains public resources and drags down economic growth (photo: People Images/iStock).[/caption]

Corruption continues to make headlines in Latin America. From a scheme to shelter assets leaked by documents in Panama, to the Petrobras and Odebrecht scandals that have spread beyond Brazil, to eight former Mexican state governors facing charges or being convicted, the region has seen its share of economic and political fallout from corruption. Latin Americans are showing increasing signs of discontent and demanding that their governments tackle corruption more aggressively.

In this first part of two blogs, we look at how corruption in Latin America compares to other regions and explain why it is so difficult to combat. Part of the answer lies in the fact that systemic corruption is so endemic to the fabric of society, that changes in behavior require a major shift in expectations. As corruption drains public resources and drags down economic growth in multiple ways, the IMF has committed to work together with our members to confront the problem.

Corruption exists in many forms

Corruption—the abuse of public office for private gain—involves illicit payments or favors and how they are distributed. However, it can take different forms. It can occur at a “grand” or political level and/or at the “petty” or bureaucratic level. When corrupt behavior is so pervasive and entrenched, it can become the norm. In these systemic cases, corruption can even affect the design and implementation of policies, and skew regulatory or state decisions such as the case of Ukraine.

Corruption could also involve individual projects and how they are awarded or renegotiated. A prominent recent example is the construction firm Odebrecht, which spent considerable resources buying the support of key public officials in exchange for contracts in several Latin American economies. Other forms of corruption occur at lower tiers, including how licenses and zoning rights are granted. While corrupt activities can be initiated either on the supply (offering a bribe) or demand side (asking for a bribe), in practice it is often hard to separate the two.

The corruption trap

Given its high social costs, why is it so hard to successfully fight corruption? As in any type of social interaction, individual beliefs and expectations are crucial. When systemic corruption is the norm, people believe that other people are accepting or offering bribes. Given these beliefs, deviating from foul play is costly from the point of view of the individual. Like in the Odebrecht example, construction companies offering bribes are more likely to get projects than ones that do not—even if the latter are more efficient. Moreover, this inefficient equilibrium is self-perpetuating because companies and politicians can collude and use proceeds from past corrupt actions to secure future benefits at the expense of society.

Countries need forceful policies that lead to changes in social perceptions so corruption is seen as the exception rather than the rule. And as corruption falls, governments will more easily detect those who remain corrupt because they will stand out.

But achieving this realignment in incentives and behavior is not easy. Fighting corruption is a collective action problem with political dimensions. Isolated efforts are not likely to work. A multifaceted and resolute push is needed to initiate positive dynamics out of the bad equilibrium. For that, strong leadership and society’s support are key.

Corruption is still a problem in Latin America

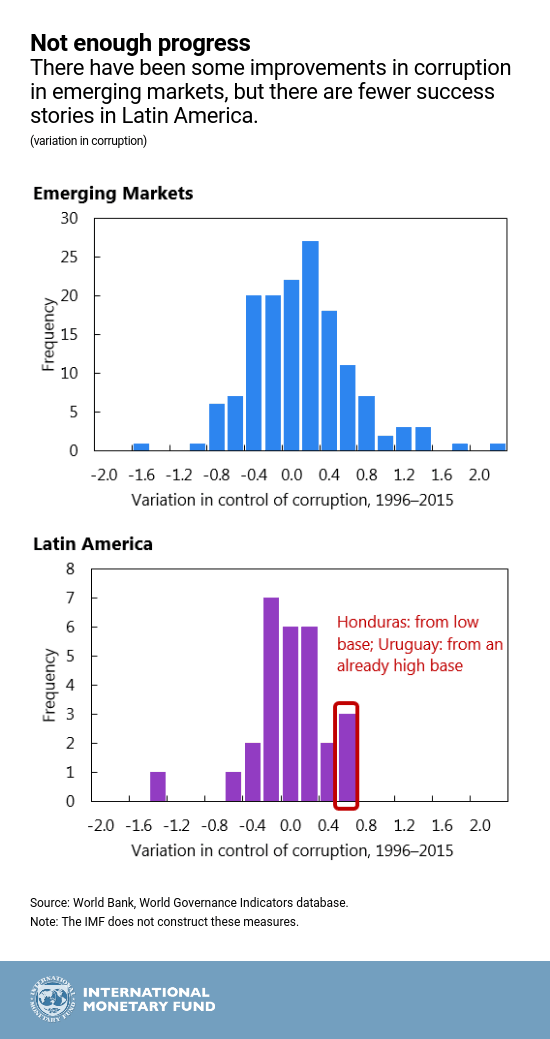

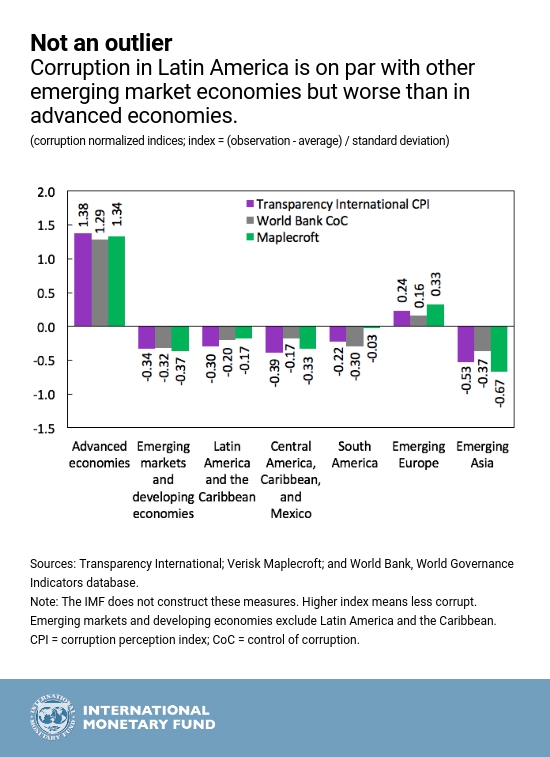

Corruption is difficult to measure, but different measures of corruption perceptions correlate quite strongly. Across these different measures, Latin America and the Caribbean appear on par with other emerging market economies, but fare substantially worse than advanced economies.

At the same time, regional averages mask a great deal of variation across countries. Corruption perceptions in some countries, such as Chile and Uruguay, are similar to levels seen in advanced economies. Interestingly, Chile and Uruguay also score well in other institutional and governance indicators, and have relatively higher income per capita levels. The rest of the region does not score as well. To varying degrees, this reflects poor law enforcement, lack of fiscal transparency, bureaucratic red tape, loopholes and weak contractual frameworks in public procurement and investment, and weak governance in state-owned enterprises.

Limited progress

It is not easy to track concrete improvements in Latin America because some measures are not fully comparable across time. Moreover, perceptions of corruption may in fact rise even when corruption falls because more is being investigated and uncovered.

While there are some cases of significant improvement over the past 20 years in emerging markets, there are fewer success stories in Latin America. For example, control of corruption in Honduras has noticeably improved (though remains high), reflecting recent actions regarding the police force, the social security administration, and the tax administration. Overall, however, most changes in Latin America are relatively small. Corruption is hard to get rid of once it’s there.

The cost of corruption

Previous studies show that corruption can hinder sustainable and inclusive growth. With systemic corruption, the state’s capacity to perform its core functions is weakened, making costs macro-critical. In addition, higher corruption tends to be accompanied by higher inequality. Some commonly recognized costs evident in parts of Latin America include: lower provision of public goods (which hurts the poor disproportionately), misallocation of talent and capital through distorted incentives, higher levels of distrust in society and lower legitimacy of government, higher economic uncertainty, and lower private and foreign investment.

Nevertheless, it is hard to statistically pin down the precise impact of corruption on development since causation runs both ways. Our illustrative estimates suggest that an improvement in corruption from the lowest quartile to the median could raise per capita income by about $3,000 in Latin America over the medium term, although part of this gain reflects coinciding factors like overall institutional improvements.

Window of opportunity

Corruption in Latin America remains too high. The latest surveys tell us that the public is losing patience, which creates a window of opportunity for national leaders. Developing and enforcing a coherent strategy to fight corruption is difficult, entails learning by doing, depends on country circumstances, and is one part of a broader development strategy. But drawing from international and regional experience can provide insights and guidance to combat corruption. Our next blog will offer some concrete suggestions for Latin America.