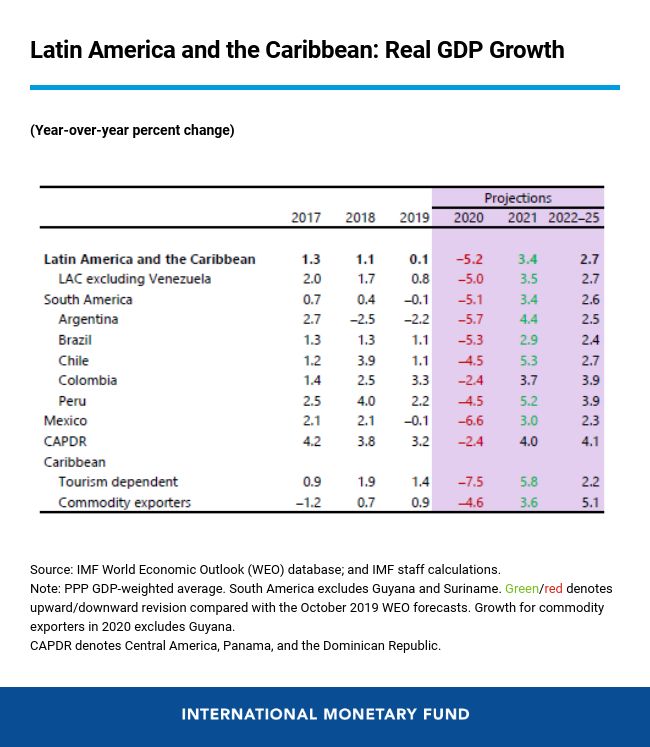

As of today, about 3,000 people have died from the COVID-19 virus in Latin America and the Caribbean. While the pandemic continues to spread across the region, countries are facing the worst economic recession since countries started producing national accounts statistics in the 1950s. The challenging external environment, coupled with much-needed measures to contain the pandemic, have led to a plummeting of economic activity across Latin America—where growth is poised to contract by 5.2 percent in 2020.

Given the dramatic contraction in 2020 and as countries implement polices to contain the pandemic and to support their economies—as emphasized in our previous blog—a sharp recovery in 2021 can be expected. Yet, even under this quick recovery scenario, the region faces the specter of another “lost decade” during 2015–25.

By now, most of Latin America has taken significant public health measures to contain the spread of the virus.

With atypical supply and demand shocks, a health crisis, and high financing costs across Latin America, the required actions to mitigate the human and economic costs of this crisis will be quite daunting and will require an unprecedented approach.

Governments respond to the crisis

Although with different speed, by now most countries in the region have taken significant public health measures to contain the spread of the virus, such as social distancing and restrictions on nonessential activities. They have also increased the amount of fiscal resources allocated to healthcare, including tests, beds, respirators, and other equipment, which is an overarching priority given that many countries are still underprepared to face the worst of the pandemic.

On the economic policy front, actions have varied. Countries have relied on direct transfers to vulnerable households (including an expansion of existing programs), relaxation of access requirements and expansion of unemployment insurance schemes, employment subsidies, temporary tax breaks and deferrals, and credit guarantees.

Sizeable packages have been announced by Brazil, Chile, and Peru, and others are expected to follow or enhance existing measures. Countries with better credit quality, as reflected in market spreads, have generally been more aggressive in their response to the pandemic.

Central banks in the region have reduced policy rates and taken measures to support liquidity and to counteract disorderly conditions in domestic financial markets. To ensure adequate liquidity conditions, some central banks have expanded the size of their liquidity provision operations, sometimes also allowing the participation of nonbank financial intermediaries and the use of highly-rated private sector securities. Several central banks (Brazil, Chile, Mexico, and Peru) have also intervened in foreign exchange and other financial markets to address disorderly conditions.

Moreover, bank regulators have taken a number of measures to facilitate the continued provision of credit in an uncertain and recessionary environment. They have made regulations less stringent, including by lowering reserve requirements, loan loss provisions and allowing the drawdown of countercyclical capital buffers on a temporary basis to facilitate the roll-over and/or restructuring of existing loans. Public banks in Brazil and Colombia have extended credit to small and medium-sized enterprises and firms in sectors particularly affected by the lockdowns, while Brazil, Chile, Peru and other countries have provided loan guarantees to help affected firms maintain and gain access to credit.

Implementation challenges

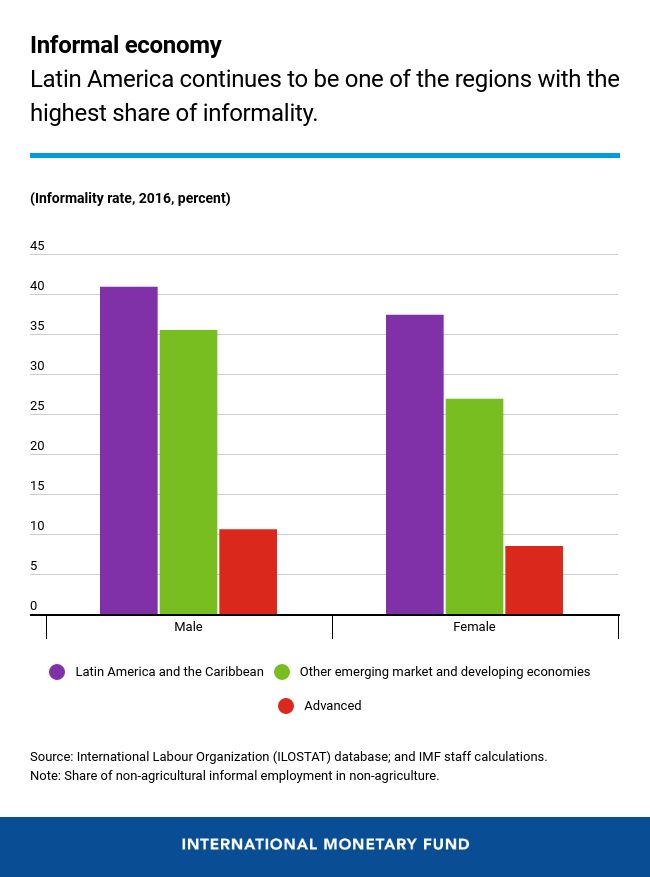

While we are in uncharted territory and policy responses are still evolving, policymakers are facing significant implementation challenges. For example, governments might be unable to reach vulnerable households through traditional transfers where there are no extensive social assistance systems already in place and where informality is prevalent. Moreover, smaller firms and those in the informal sector are harder to reach. Given the high level of informality in the region, countries should use all possible registries and methods to reach smaller firms and informal workers and firms.

Additionally, given that the pandemic, the recession, and the required policy responses will cause significant increases in public deficits and debt, countries will need to create fiscal space in the budget by reducing nonpriority expenditure and increasing the efficiency of spending.

Countries will need to ensure that policies taken in response to the crisis are not perceived as permanent and become entrenched and generate distortions—especially regarding targeted assistance to certain sectors. Several countries with fiscal rules on permissible deficits and/or on how much their governments can spend have rightly invoked escape clauses to allow for extraordinary increases in government spending and deficits (Brazil, Chile, Peru, among others), but policy makers should communicate a clear path back towards compliance with these rules over the medium term.

To provide much needed additional revenue to help finance all these initiatives, increased taxation of petroleum products at a time when world prices are lower could be appropriate insofar that they do not increase domestic prices to end users. Moreover, the tension between what is needed and what is possible is also subject to change by policy action. Those countries that can credibly commit to a sustainable fiscal policy by changing their tax, expenditure, and fiscal frameworks that guarantee corrections once the economy is back on track, will unlock significant fiscal space in the present to address the fall out.

Monetary policy actions

There is scope for further cuts in policy rates and liquidity support. Large output gaps and lower-for-longer rates in advanced economies suggest some central banks in the region could cut rates further, but large capital outflows may pose constraints on further policy easing.

Commercial banks may be wary to lend to risky sectors in a deep recession, so credit risk could be mitigated by direct lending or explicit guarantees provided by the government through development banks or special purpose vehicles set up to fulfill this objective.

Prudent and temporary use of regulatory flexibility, such as providing debtors some breathing space before classifying loans as past due and postponing associated costly provisions , has been applied in some countries to facilitate rollovers.

How the IMF can help

Several countries in the region will not be able to access sufficient resources on their own to cover the large external financing. So far, out of close to a 100 countries that have requested emergency financing from the IMF, 16 are from Latin America and the Caribbean. Additionally, other Latin American and Caribbean countries have requested new programs or the augmentation of existing ones, such as Honduras.

As this is an unprecedent crisis, the IMF is actively engaged and fully committed to help our member countries fill this gap through several tools. These include using its 1-trillion-dollar balance sheet, expediting the approval of lending facilities, increasing the limits of existing facilities, and providing debt relief to the poorest and most vulnerable member countries hit by the pandemic under the revised Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust. Besides the emergency facilities, the Fund is ready to deploy its more traditional arrangements (such as Stand-by and Extended Fund Facilities) as well as its contingent credit lines (such as flexible credit lines and precautionary credit lines).

As our Managing Director, Kristalina Georgieva, has noted, saving lives and protecting livelihoods ought to go hand in hand. We cannot do one without the other. We at the IMF are working on making sure that there is a strong response to the health crisis as well as protecting the strength of economies.