On the Ball

Finance & Development, March 2014, Vol. 51, No. 1

European soccer’s success can be credited, in part, to the liberalization of the players’ market. But what will the future bring?

The soccer World Cup in Brazil will be the biggest sporting event of 2014, likely dominating the news and lives of fans for many months. For some of the players, this will also be the defining moment of their careers.

Attention will focus on established soccer stars such as Argentina’s Lionel Messi and Portugal’s Cristiano Ronaldo and whether they can do as well for their countries as for their clubs (Barcelona and Real Madrid, respectively).

The World Cup will also create several new millionaire players—players currently working for small clubs in places like Costa Rica, Croatia, Greece, or Japan will earn lucrative contracts with mega clubs such as Bayern Munich and Manchester United on the back of star performances in Brazil. Almost every player’s ambition will be to play at the highest level in Europe.

Thanks to fundamental changes in the regulatory regime and other factors, international mobility in Europe’s soccer labor market has increased markedly in the past two decades. Today, the size of the expatriate labor force in European soccer (at more than one-third of the total) far exceeds that in the wider European labor market, where foreigners comprise only 7 percent of the labor force (Besson, Poli, and Ravenel, 2008; European Commission, 2012). This internationalization is a key factor in Europe’s soccer success.

Early evolution

Soccer was first organized in England in 1863 and spread rapidly to the rest of Europe. It was one of the first manifestations of globalization, with the World Cup, which started in 1930. Today the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), the sport’s world governing body, has more national members than the United Nations.

But if soccer is the world’s game, it is also true that the biggest teams and markets for playing talent are in Europe. According to FIFA’s “Big Count” survey published in 2006, there are approximately 113,000 professional soccer players worldwide, of whom 60,000 work inside the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA), the European governing body (Kunz, 2007). UEFA calculated that in 2011 the total income of European soccer was €16 billion, of which €6.9 billion was paid out as wages. European football is successful in that it has the biggest clubs, the best national teams (only Brazil and Argentina rank alongside European nations such as Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain), the largest national leagues, and the biggest competitions.

Labor mobility has played a significant role in maintaining Europe’s dominance. In the early days, players bid away by higher wages would frequently change teams within the same season. But the clubs banded together and instituted a transfer system, which required that each professional player be registered with a club. The registration was the club’s property, and the player could not play for another club until it was transferred. Initially the club held the registration in perpetuity unless it chose to sell it, effectively tying the player to the club. This system mainly ensured that player salaries remained low. In the 1960s, players started to secure greater rights, such as the freedom to move when their contracts ended.

International player migration became an important part of soccer beginning in the 1950s. Argentine Alfredo Di Stefano and Hungarian Ferenc Puskás were the backbone of the great Real Madrid team of that era, and in the 1960s, Spanish and Italian teams sought to attract the best players from Europe and South America. But until the 1990s, mobility was mostly domestic.

More broadcast competition following the development of cable and satellite technologies in the 1980s significantly enhanced the demand for sports content and created an international audience for league soccer. Greater competition also increased the thirst for international talent. In 1992, only nine foreign players were playing in the English Premier League, but by 2013 this number had risen to 290, accounting for two-thirds of all soccer players. While the figures are less dramatic for other European leagues, the proportion of foreigners playing in Germany is about 50 percent, and in Spain, about 40 percent.

Bosman ruling

Deregulation has done much to diversify the European soccer labor market. Sports organizations are private associations and, as such, have considerable latitude to set their rules and regulations free from government interference. However, restrictive employment agreements can fall foul of the legal system, as happened in the landmark “Bosman ruling.”

Jean-Marc Bosman was a Belgian player with the Belgian club Liège whose contract had expired; the French team Dunkerque wanted to hire him and he wanted to move. Dunkerque offered to pay a transfer fee for his registration, which, under the rules at the time, still belonged to Liège. Liège considered the offer inadequate, and so Bosman could not move. Bosman sued, and the case went to the European Court of Justice. In 1995 the court ruled that the rules of the transfer system contravened EU laws on the free movement of labor and that rules restricting the number of foreign players also breached the law (European Court of Justice, 1995). This ruling was widely seen as facilitating a big increase in cross-border migration of players.

As a result, the transfer regulations were significantly recast in negotiation with the European Commission. Since then, transfer fees are applicable only to players whose contracts have not expired, except for those under the age of 23, to compensate for training. Clubs participating in UEFA competition must field a minimum of eight “homegrown” players—at least four trained by the club itself and another four from the national association.

At the time, many experts argued that the Bosman ruling would destroy the transfer market, and with it the economic viability of smaller clubs. Neither forecast proved correct. The transfer fee record has been broken several times, most recently in 2013 when Tottenham player Gareth Bale, with three years left on his contract, moved to Real Madrid for a fee of €100 million. Many clubs find themselves in significant financial difficulties, but this has always been the case in soccer—yet clubs rarely exit the market. Instead, their losses are often absorbed by “sugar daddies,” wealthy individuals who relish the considerable prestige that goes with the ownership of a soccer team.

Labor market efficiency

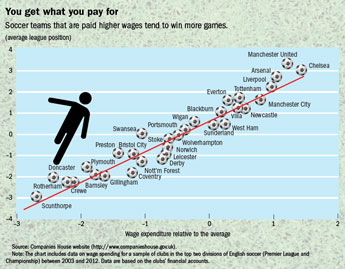

For all of the obvious success of European soccer with its flexible labor market, it is more difficult to assess its economic efficiency. The relationship on average between wage spending and team success for the top two divisions of English football over the past two decades is strongly correlated (see chart). There are many reasons to believe that this relationship is causal: players are widely and openly traded in the market, player characteristics are well known and frequently observed, better players tend to win more games, and teams that win generate more income. In some ways, the soccer labor market represents perfect competition.

Reverse causality seems unlikely: while players may earn contractually stipulated bonuses when the team wins, it seems unlikely that a successful club would pay higher wages just because it could—most clubs want to invest in future success and are quite willing to trade players they think are no longer performing. More sophisticated models that seek to control for potential feedback effects tend to support the hypothesis that causation runs from wages to success (Peeters and Szymanski, forthcoming). Moreover, the relationship identified here for English soccer has been found in other leagues, such as Spain, Italy, and France.

Sustaining fan interest

The data imply that players are, on average, priced efficiently in the market, in the sense that the wage paid is proportionate to the success of the team. However, it is less clear that this is an efficient outcome for European soccer as a whole.

From an economic perspective, the players should move to teams where their “marginal revenue product” is maximized—that is, where they can make the greatest possible contribution to the team’s success. The contribution of a win to revenue is clearly highest at a small number of clubs that have traditionally dominated national leagues, but many economists have argued that the perpetual dominance of a league by a small number of teams is inefficient.

The argument is that a degree of “competitive balance” is required to make a league attractive, or there will be no uncertainty of outcome—in which case fans will lose interest, even in successful teams. (What is the point of watching a game if you already know the outcome?) Successful teams will destroy the interest in the competition if they are too dominant (Rottenberg, 1956). The league should promote competitive balance by the redistribution of resources.

From the perspective of the labor market, this suggests that the dominant clubs have an incentive to overinvest in talent relative to the best interests of the league and the fans, and the smaller clubs choose to underinvest. Consequently the allocation of players in an unrestricted market is socially inefficient—the big clubs will be too strong and the small clubs too weak. This problem is taken seriously in the United States, where a wide array of mechanisms has been adopted by professional sports leagues to equalize competition.

For example, in the National Football League (NFL), the most profitable sports league in the world, 40 percent of gate revenue is shared with the visiting team and all broadcast and merchandising revenue is shared equally among the 32 teams in the league. A salary cap limits the amount teams can spend on players, a salary floor dictates a minimum, and a draft system rewards the worst-performing team in the league with the first pick of new talent. All these rules aim to equalize competition, and the NFL boasts that “on any given Sunday, any team in the league can win.” There is almost no correlation between wage spending and team performance, because there is almost no variation in wage spending.

The evidence in favor of an NFL-like system is surprisingly mixed, given that the highly unbalanced European system has continued to generate much fan interest (Borland and MacDonald, 2003). But rules imposed for the sake of competitive balance tend to constrain wages and labor mobility. The NFL draft gives exclusive bargaining rights to a single team, for example, while players entering the league are tied to a four-year contract. Should a player turn out to be far better than expected, he has little prospect of a better deal until the four years are over. This regime has been negotiated with the players’ union, which secures agreements on minimum terms and conditions in exchange. Such constraints make the NFL teams profitable and give the players security. By contrast, in Europe, teams are largely unprofitable, and the player union FIFPRO claims that many players are not paid on time or in full.

In the current year, a new system of financial regulation called “Financial Fair Play,” which seeks both to enforce contractual obligations on clubs and restrain spending on players, will go into effect in Europe. The likely outcome of these regulations, if fully enforced, will be to reduce player mobility and increase the profitability of clubs. Whether it heralds a trend toward a more American style of league organization remains to be seen.

Stefan Szymanski is the Stephen J. Galetti Professor of Sport Management at the University of Michigan.

References

Besson, Roger, Raffaele Poli, and Loïc Ravenel, 2008, Demographic Study of Footballers in Europe, International Center for Sports Studies report (Neuchâtel, Switzerland).

Borland, Jeff, and Robert MacDonald, 2003, “Demand for Sport,” Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Vol. 19, No. 4, pp. 478–502.

European Commission, Eurostat, 2012, European Union Labour Force Survey—Annual Results 2012 (Luxembourg).

European Court of Justice, 1995, Case No. C–415/93, Report p. I–04921 (Luxembourg).

Kunz, Matthias, 2007, “265 Million Playing Football,” Big Count Survey, FIFA Magazine, July.

Peeters, Thomas, and Stefan Szymanski, forthcoming,“Financial Fair Play in European football,” Economic Policy.

Rottenberg, Simon, 1956, “The Baseball Players’ Labor Market,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 64, No. 3, pp. 242–58.