A Broader Mandate

Finance & Development, June 2014, Vol. 51, No. 2

Luis Jácome and Tommaso Mancini-Griffoli

Central banks are feeling pressure to expand their inflation brief to include politically charged goals such as employment and growth

In the decades leading up to the 2008 global financial crisis, country after country became persuaded that to achieve price stability, central banks should focus solely on that goal and operate independently of political authorities, who often have short-term horizons. But in recent years that consensus has frayed somewhat, as authorities and others have come to reassess the role that central banks should play.

A number of academics and analysts have suggested that central banks should embrace a broader mandate that adds to inflation aims. Perhaps the most concrete suggestion is that central banks play an active role in preserving financial stability, avoiding systemic financial crises by limiting excessive credit growth and borrowing. This would take the central bank beyond today’s role of regulating individual banks. Some suggest that central banks should have a dual and equal mandate of controlling inflation as well as supporting full employment and growth. Under most current mandates, central banks concern themselves with employment and growth only as far as they affect inflation.

But such a broader mandate would inevitably come to rub against political considerations, and unelected central bankers could see their independence constrained. We examine the channels through which independence could wane—and the associated costs. We argue that depending on the mandate, it may well be justified for central banks to have less independence, but that legal and institutional arrangements should protect the core of monetary policy independence—which has worked so well in containing inflation.

While some central banks could see their mandates expand, others might see them reduced. In an environment of potentially severe fiscal difficulties for governments, central banks could feel significant pressure to ease financing strains—for example, by keeping interest rates low. Central banks should prepare for this pressure.

Roots of independence

The value of granting central banks independence from government authorities in setting monetary policy is well rooted in economic theory. Kydland and Prescott (1977), Barro and Gordon (1983), and Rogoff (1985) all showed that independent central banks tend to avoid the inflationary bias that occurs as a result of self-interested political intervention. In proposing to grant independence to the Bank of England when he became prime minister in 1997, Tony Blair said he became “convinced long ago that for politicians to set the interest rate was to confuse economics and politics.”

Central bank independence has largely proved effective in achieving and preserving low inflation. It has been extensively documented that higher independence and lower inflation go hand in hand (Cukierman, 2008). Latin America is a case in point. The region today has one of the lowest and most stable inflation rates in the world, although there are a few exceptions. That is in sharp contrast to its history of very high inflation—which reached more than 500 percent in 1990—before most Latin American nations granted independence to their central banks.

The case for making central banks independent is not self-evident. The public must have substantial confidence in the bank’s ability to carry out its mandate and in the benefits that will accrue to society. On the face of it, it is unusual to concentrate significant control over the economy in an institution ruled by authorities who lack formal and broad popular support. Three key attributes of central banks seem to have facilitated their independence and contributed to their credibility:

A clear monetary policy framework: Central banks use specific instruments (a short-term interest rate) to target a measurable objective (inflation). This has allowed the public to monitor the actions of central banks and, importantly, evaluate their success in meeting their objective.

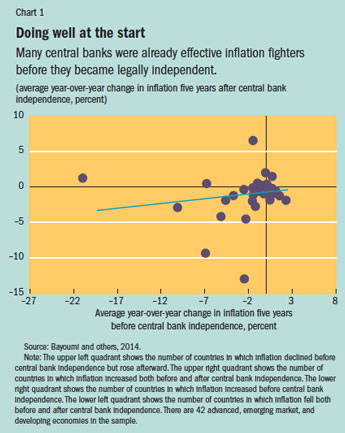

Performance: Central banks’ successful track record in reducing inflation often appears to be a precursor to legal independence (see Chart 1). In turn, as suggested earlier, central bank independence also seems to have helped perpetuate low inflation by shielding central banks from political interference.

Accountability: In many countries, the goal of monetary policy is set by the government and is generally widely perceived to contribute to the social good for the most part. As such, central banks give up “goal independence,” but maintain “instrument independence” to the extent that they can freely define and manage the policy instruments they use to achieve that goal. Interestingly, whether central banks have instrument independence alone or both goal and instrument independence does not seem to have much effect on the achievement of their objectives (Bayoumi and others, 2014). Central banks frequently report their decisions and progress toward their objective to the government and congress.

Expanded mandates

Central banks may see their mandates expand. They may be asked to play a more active role in supporting financial stability and may be required to respond more actively when output and employment deviate from their potential.

Central banks’ responsibility to preserve financial stability may go well beyond the role of regulator and supervisor, which is the most common approach today and focuses on ensuring the health of individual financial institutions, such as banks. Central banks may become major players in the design and execution of so-called macroprudential policy, which aims to tackle risks to the system as a whole, not just to individual institutions (see “Protecting the Whole,” in the March 2012 F&D). And even if macroprudential policies are set outside the perimeter of the central bank, they must be taken into account by monetary policy and perhaps complemented with higher interest rates in good times to help slow credit growth and borrowing.

Whether central banks should care more about economic growth and employment than they now do is less obvious. Some argue a shift is warranted, citing a weaker trade-off than in the past between inflation and employment—the old Phillips curve proposition that higher employment is accompanied by higher inflation and vice versa. It is true that inflation decreased much less than expected during the recent crisis despite the extremely sharp recession, but we still do not know enough about why. The underlying causes could be temporary or specific to certain countries. Alternatively, inflation may be well anchored because of years of targeting the overall price level and placing less weight on growth and employment. If that is true, increasing emphasis on growth and employment because inflation has been stable could be self defeating; it could undermine the very justification for doing so. Yet monetary policymakers are likely to be pressured to shift their attention toward growth and employment. Some of this pressure might come from self-interested political leaders who want short-term support from monetary policy to boost growth around election time.

Risk of undermining independence

A broader central bank mandate could erode each of the three features that facilitate central bank independence. In turn, this could weaken monetary policy’s ability to preserve price stability.

The public could find it harder to monitor the central bank under a broader mandate. The inflation rate is easy to measure and compare against the central bank’s objective. Financial stability, however, is inherently difficult to measure. What is measurable is instability—exactly what central banks want to avoid. In addition, there could be public confusion because instruments used to support systemic stability may change over time and may overlap with those used for monetary policy—for example, if interest rates, which are a monetary policy tool to affect inflation, are used to help stem credit growth as part of a financial stability effort.

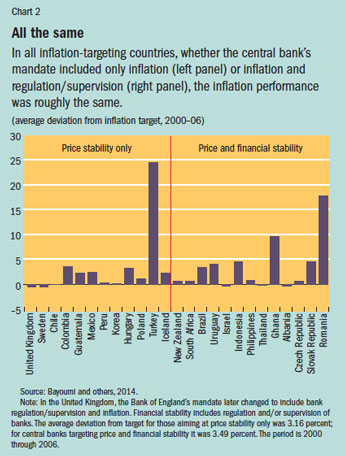

Independence could come under scrutiny if the performance of central banks falters, which could happen under multiple mandates. There is no evidence that the regulatory role of central banks has had any effect on the success of monetary policy, in particular where there is a well-established monetary policy framework—such as inflation targeting (see Chart 2). But if mandates encompass financial stability, central banks could lose credibility—due to external shocks or contagion or through unforeseen channels—despite their efforts to contain a financial crisis.

Risks to central bank credibility from weak performance would be even greater if the central bank were held accountable for growth and employment. Clearly, monetary policy can affect economic growth in the short run, but the effect will wane significantly over time as other policies kick in, particularly those that affect labor markets and productivity. It would be very difficult to separate the effect of monetary policy from that of other factors when assessing central bank performance.

Using monetary policy to spur growth and employment would be even less effective in emerging market and developing economies, where economic performance is often influenced by external shocks (such as changes in commodity prices or U.S. interest rates). Moreover, expanding the mandate of central banks to include economic growth could well take pressure off needed reforms in other sectors. In turn, failure to secure sustainable economic growth and high employment would undermine central bank credibility.

A broader mandate also risks undermining accountability. Decisions relative to financial stability may not always be seen as contributing to the social good because they directly and explicitly influence wealth redistribution, spending decisions, output, profits of the financial sector, and banking costs. For example, if a central bank decides to tighten loan-to-value ratios, the resulting higher down payment required for a house purchase would make it harder for low- and middle-income families to obtain credit in the short run. Of course, inflation also affects income distribution between savers and borrowers, young and old. But these effects are less directly observable when inflation is low and are clearly negative for society at large when inflation is high. It is thus easier to agree on a socially acceptable low inflation target than on a financial stability objective.

Government officials are likely to want to get directly involved in a broader central bank mandate. Members of the government may rightfully want to have a say, and even a seat on central bank decision-making committees that touch on economic growth and could have taxpayer or obvious redistributive implications—for instance, if the central bank is given responsibility for crisis resolution.

While greater political oversight of the central bank may be warranted for certain decisions, it will be important, at the least, to preserve the instrument independence of monetary policy. This will mean insulating monetary policy decision-making structures from political interference—for example, distinct decision-making committees with clear and separate objectives and, as much as possible, clear division between the instruments that fight inflation and those that support financial stability. Clear communication will also be essential, especially when a monetary policy decision affects or is affected by financial stability concerns. The task appears manageable, though challenging. But it would seem to be much more daunting if output and employment were explicitly added to the mandate mix.

Surviving fiscal dominance

Probably the worst scenario for central bank independence is one in which a crisis in public finances subordinates monetary policy objectives and operations to the need to support government coffers—a situation called fiscal dominance. In this extreme case, monetary policy loses independence; it is relegated to keeping interest rates low to reduce government borrowing costs.

When fiscal dominance prevails, one risk is the loss of control over inflation. Inflation expectations may increase once markets realize there is a change in the central bank’s objective and that public finances are unsustainable. Whether public finances are on the cusp of sustainability in advanced economies is beyond the scope of this article. But they are clearly under strain—debt-to-GDP ratios increased in advanced economies from 60 percent to more than 100 percent between 2007 and 2013 (IMF, 2013). Most emerging market and developing economies, however, reduced debt-to-GDP ratios and kept fiscal deficits in check, which gave them leeway to offset some of the effects of the global crisis.

Perhaps the more tangible risk is that markets believe that monetary policy has turned its back on its traditional objective to support public finances. This risk is especially high in countries whose central banks maintain extraordinarily large balance sheets—through big bond purchase programs, for example. The risk would also materialize if central banks decided to target longer-term interest rates in the future. Central banks might be unable to convince markets that their purchases of longer-term bonds were justified by monetary policy or financial stability objectives, not fiscal ones. Clearly, these concerns grow with the level of a country’s debt and the duration of bond purchases.

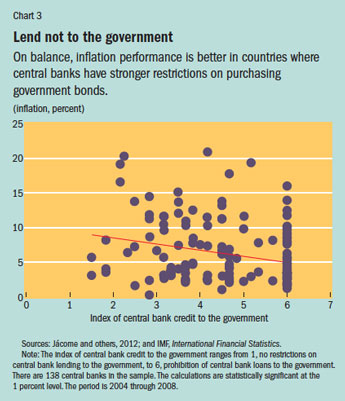

Misperceptions of a change in monetary policy objectives would be costly. Monetary policy would have to increase interest rates by more than before to achieve the same stabilizing effect on the economy. Among the vast amount of evidence pointing to the cost of an inflation risk premium, some suggests that central banks with stronger restrictions on purchasing government bonds exhibit better inflation performance (see Chart 3).

Fiscal dominance could become a reality in countries that fail to build buffers in good times in preparation for bad times. So central banks should prepare to face significant pressure to keep inflation high and reduce pressure on public finances. As a last resort, discussions with the government should be settled cooperatively, potentially with some central bank support for concrete and credible measures to meet medium-term debt sustainability targets. The level of cooperation required, though, is new and will have to be built over some time. Whatever the framework, transparency and communication will be key to preserving central bank credibility and economic stability. ■

Luis Jácome is a Deputy Division Chief and Tommaso Mancini-Griffoli is a Financial Sector Expert, both in the IMF’s Monetary and Capital Markets Department.

References

Barro, Robert, and David Gordon, 1983, “A Positive Theory of Monetary Policy in a Natural Rate Model,” The Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 91, No. 4, pp. 589–610.

Bayoumi, Tamim, Giovanni Dell’Ariccia, Karl Habermeier, Tommaso Mancini-Griffoli, and Fabián Valencia, 2014, “Monetary Policy in the New Normal,” IMF Staff Discussion Note 14/3 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Cukierman, Alex, 2008, “Central Bank Independence and Monetary Policymaking Institutions: Past, Present, and Future,” European Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 722–36.

International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2013, Fiscal Monitor (Washington, October).

Jácome, Luis I., Marcela Matamoros-Indorf, Mrinalini Sharma, and Simon Townsend, 2012, “Central Bank Credit to the Government: What Can We Learn from International Practices?” IMF Working Paper 12/16 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Kydland, Finn, and Edward Prescott, 1977, “Rules Rather Than Discretion: The Inconsistency of the Optimal Plans,” The Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 85, No. 3, pp. 473–91.

Rogoff, Kenneth, 1985, “The Optimal Degree of Commitment to an Intermediate Monetary Target,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 100, No. 4, pp. 1169–89.