Private vs. Public

Finance & Development, December 2014, Vol. 51, No. 4

Jorge Coarasa, Jishnu Das, and Jeffrey Hammer

In many countries the debate should not be about the source of primary health care but its quality

The private sector provides between one-third and three-quarters of all primary health care in low-income countries, depending on the survey. But for most patients private sector medicine does not encompass large, modern hospitals and integrated service providers. That private sector exists and caters to a relatively wealthy urban clientele. The private sector for the poor is a mixture of modern providers operating small for-profit clinics or working for nonprofit institutions and providers trained in traditional systems of medicine, herbalists, homeopaths, and many with no qualifications.

It is impossible to generalize about what the private sector is or does in providing medical services to the poor. Nevertheless two generalizations seem to dominate the discussion of private medicine in low-income countries. One promotes the private sector as a cure-all for public sector malaise and general dysfunction. The other believes that predatory practices are so endemic in the private sector that it should be regulated, controlled, and possibly replaced by government-funded and -operated clinics.

To what extent each view is right is an empirical question that depends on the problems that arise when patients and health care providers interact in markets for medical care and on the ability of the government to fix them. For example, patients may not recognize good care and instead demand quick fixes and snake-oil remedies. If they do, the private sector will provide such remedies. Or providers may prescribe treatments that increase their financial benefit, not serve the patient’s health needs. For instance, providers may choose cesarean sections when cheaper, normal deliveries are sufficient or dispense unnecessary medicines that earn the provider a profit. Indeed, it is widely believed that “asymmetric information”—when the provider knows more about the patient’s condition than the patient does—leads to problems with the private provision of curative health care.

But it is not clear that governments do better. Low-quality private providers and serious market inefficiencies often coexist with low-quality public sector providers. Potential regulators often lack monitoring and enforcement capacity. True public goods—such as the elimination of sources of disease (mosquitoes for example) and good sanitation—must be provided by the government. But when it comes to curative medical care, the picture is less clear.

Large private sector

The private health care sector in low-income countries is generally large and a steadily used source of primary care, despite increases in funding and elimination of user fees for public services in many countries. Demographic and Health Surveys asked household members where they sought care when a child had a fever or diarrhea. Between 1990 and 2013 (across 224 surveys in 77 countries) half the population turned to the private sector, and between 1998 and 2013—even among the poorest 40 percent—two-fifths sought private care (Grepin, 2014). For adult and childhood illnesses combined, private sector use in the early 2000s (the latest data available) ranged from 25 percent in sub-Saharan Africa to 63 percent in south Asia (Wagstaff, 2013).

One possible explanation for large private sector use is unavailable or overcrowded public facilities, which drives people to private clinics. But people use private providers extensively even when public facilities are available. And overcrowding does not appear to be an issue. In Tanzania, Senegal, and rural Madhya Pradesh (India), doctors in public primary health clinics spend a mere 30 minutes to an hour a day seeing patients. In Nigeria, the average rural public facility sees one patient a day (World Bank, 2011; Das and Hammer, 2014).

The willingness of patients to pay for private services they could get free from a nearby underutilized public facility could reflect various dimensions of quality, such as provider absenteeism in public facilities or inadequate customer attention. From a health and policy standpoint, the preference for private facilities becomes a problem if private sector providers are more likely than public providers to yield to patient demands for products and services that are medically inappropriate (antibiotics and steroids, for example) or to manipulate treatment to increase their incomes. If both problems are less prevalent in the public sector, governments should consider expanding the public sector to replace the private sector or think about closely regulating private medicine. The question is whether the quality of care differs across the two sectors.

Quality of care

In fact, the overall quality of care in both sectors is poor. Consultation time varies from as little as 1.5 minutes (public sector, urban India) to 8 minutes (private sector, urban Kenya). Providers ask on average between three and five questions and perform between one and three routine examinations, such as checking temperature, pulse, and blood pressure. In rural and urban India, important conditions are treated correctly less than 40 percent of the time; when patients receive a diagnosis, it is correct less than 15 percent of the time. Unnecessary and even harmful treatments are widely used by all providers and in all sectors, and potentially lifesaving treatments, such as oral rehydration therapy in children with diarrhea, are used in less than a third of interactions with highly qualified providers. Less than 5 percent of patients receive only the correct treatment when they visit a provider.

Two recent systematic reviews of studies of the quality and efficiency of public and private sector health service provision came to sharply different conclusions. One supported the public sector (Basu and others, 2012) and the other the private sector (Berendes and others, 2011). When we went to the original literature to identify the source of this discrepancy, we were forced to conclude that the short answer to even the basic question of whether the quality of care is higher in the public or private sector is “we don’t know.”

To isolate quality differences across the public and private sector, studies should have data from both. They should also rule out confounding factors arising from differences in patients, training, and resource availability. (It is not useful to compare an untrained private sector provider in a small rural clinic with a fully trained public sector doctor in a well-equipped hospital).

Of the 182 publications covered in the two reviews, only one study (Pongsupap and Van Lerberghe, 2006) satisfied these criteria. This study used standardized patients (mystery clients) to examine how “similar” doctors in the private and public sectors in Bangkok treated anxiety. Standardized patients—local recruits who present the same situation to several providers—are widely regarded as the gold standard in this type of research because they offer an objective measure of quality of care, including how likely the provider is to follow protocols, the accuracy of the treatment, and the use of unnecessary treatments. They allow researchers to evaluate how the same patient is treated by different providers. In that study, the authors reported more patient-centered care in the private sector, but no difference in treatment accuracy between public and private providers. No doctor provided the correct treatment (which was to do nothing).

Rural India

In our own research in rural India, we sent standardized patients first to a random sample of providers in the public and private sector and then to qualified doctors who practiced in both (Das and others, 2014). There are several notable findings.

First, the majority of care in both the public and private sector was provided by people without formal medical training. In the private sector, this reflects the paucity of trained professionals willing to practice in rural areas. In the public sector, a medically untrained staff member provided care 64 percent of the time because a doctor was not present. Doctors, who are paid a fixed salary, are often absent from public clinics—40 percent of the time in India, 35 percent in Uganda, and more than 40 percent in Indonesia, according to national studies.

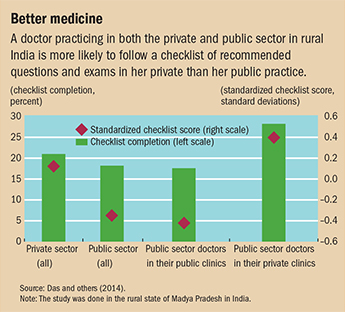

Second, patient-centered interactions and treatment accuracy were highest in private sector clinics with public doctors. The same doctor spends more time, asks more questions, is more likely to adhere to a checklist of recommended questions and examinations, and has higher treatment accuracy in a private than public practice (see chart). There is no difference in the (high) use of unnecessary medicines across sectors.

Third, antibiotic overuse was equally high in both sectors. In the private sector 48.2 percent of qualified and 39.4 percent of less than fully qualified providers dispensed unnecessary antibiotics. Public doctors in primary health clinics prescribed antibiotics for diarrhea 75.9 percent of the time, spending 1.5 minutes to reach a treatment decision.

Fourth, in the private sector, greater adherence to a checklist and correct treatment meant higher prices. This is consistent with market models in which consumers pay a premium for better quality and suggests that they know the quality of the services and care about treatment accuracy. But there was no price penalty for unnecessary treatment, suggesting that patients could not judge whether extra medicines they received were necessary.

The overuse of medicines in the private sector could reflect a link between provider profits and prescribing practice: research shows that when doctors receive no compensation as a result of prescribing them, unnecessary antibiotics are prescribed less often. But antibiotic use is just as high in the public sector. So the profit motive may be part of the story, but it is not the only story. Similarly, the conventional wisdom that patients cannot judge quality must also be challenged because legitimate medical quality differentials are correlated with higher prices.

Encouraging better medicine

On the basis of what little evidence there is, the ills of the private sector have been exaggerated. Patients appear to make logical choices driven by factors such as distance, waiting times, prices, and the quality of care. There is scant evidence that patients make irrational decisions to visit private clinics. Although medicines tend to be overused when private health care providers both diagnose patients and receive compensation for their treatment, the same kinds of problems exist in the public sector.

The issue underlying the private-public question is not patient ignorance or irrational behavior, but the overall quality of care, which is low in both sectors. Better infrastructure and training may be necessary, but alone they are not enough to raise the quality of care (Das and Hammer, 2014). The behavior of health care providers and the structures and incentives affecting their work must be changed. To reduce the use of unnecessary medicines, for example, policies should remove the link between diagnosis and treatment in both sectors. This would include a legal barrier between prescribing and dispensing medicines and medical testing.

There is no reason to expand public medical care unless it is at least as good as the services it displaces. Expansion of public care might be appropriate in the rare country whose private market failure is particularly bad and whose public sector accountability is particularly good. But even then governments would have to greatly expand the capacity of the public sector or set up a massive regulatory system. A simpler option may be to focus first on what is already there and try to improve it. If policymakers accept that people don’t use the public sector because its quality is poor and focus on making things better, patients would choose the best option. ■

Jorge Coarasa is Senior Economist and Jishnu Das is Lead Economist, both at the World Bank, and Jeffrey Hammer is a Visiting Professor in Economic Development at Princeton University.

References

Basu, Sanjay, Jason Andrews, Sandeep Kishore, Rajesh Panjabi, and David Stuckler, 2012, “Comparative Performance of Private and Public Healthcare Systems in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review,” PLoS Medicine, Vol. 9, No. 6, p. e1001244.

Berendes, Sima, Peter Heywood, Sandy Oliver, and Paul Garner, 2011, “Quality of Private and Public Ambulatory Health Care in Low and Middle Income Countries: Systematic Review of Comparative Studies,” PLoS Medicine, Vol. 8, No. 8, p. e1000433.

Das, Jishnu, and Jeffrey Hammer, 2014, “The Quality of Primary Care in Low-Income Countries: Facts and Economics,” Annual Review of Economics, Vol. 6, pp. 525–53.

Das, Jishnu, Alaka Holla, Michael Kremer, Aakash Mohpal, and Karthik Muralidharan, 2014, Quality and Accountability in Health: Audit Evidence from Primary Care Providers (Washington: World Bank).

Grepin, Karen, 2014, “Trends in the Use of the Private Sector: 1990–2013: Analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys” (unpublished; New York: New York University).

Pongsupap, Yongyuth, and Wim Van Lerberghe, 2006, “Choosing between Public and Private or between Hospital and Primary Care: Responsiveness, Patient-Centredness and Prescribing Patterns in Outpatient Consultations in Bangkok,” Tropical Medicine & International Health, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 81–89.

Wagstaff, Adam, 2013, “What Exactly Is the Public-Private Mix in Health Care?” Let’s Talk Development (blog), Dec. 2.

World Bank, 2011, “Service Delivery Indicators: Pilot in Education and Health Care in Africa,” African Economic Research Consortium Report (Washington).