Seven Lean Years

Finance & Development, March 2015, Vol. 52, No. 1

The global economy is in slow recovery from peak unemployment thanks to governments’ vigorous policy responses

The onset of the Great Recession in 2007 led to job losses around the world not seen since the Great Depression of the 1930s. By 2010, 30 million more people had joined the ranks of the unemployed. About three-quarters of this increase took place in high-income economies.

Emerging markets and low-income countries, which in the past have borne the brunt of global recessions, were more resilient this time. In emerging markets the unemployment rate barely budged—an increase of only 0.25 percentage point by 2010—and in low-income economies it actually declined.

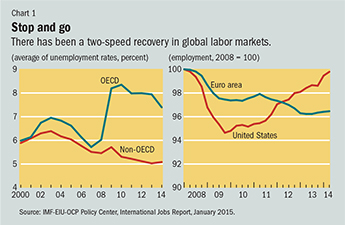

Since 2010, the global economy has mounted a slow and uneven recovery. The global unemployment rate has now returned to its 2007 pre–Great Recession level of about 5 1/2 percent. In the high-income group—member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)—it shot up to 8 1/2 percent in 2010 and has slowly inched back to 7 1/2 percent (see Chart 1, left panel). Although employment grew at a fast pace in the United States over the past year, it remained relatively flat in the euro area, the region largely responsible for the anemic recovery in global employment (see Chart 1, right panel).

“Strucs vs. cycs”

Over the course of 2009–11, there were “two gangs of economists warring over the causes of high unemployment,” as an article in Slate noted at the time.

One camp, the “cycs,” argued that cyclical factors were the predominant, if not the only, cause. Their ringleader, U.S. Nobel Prize winner Paul Krugman, wrote: “Why is unemployment remaining high? Because growth is weak—period, full stop, end of story.” To this camp, the reason for weak growth was insufficient demand, which the government should try to stimulate through easy monetary policy and fiscal stimulus.

The “strucs,” on the other hand, argued that unemployment was high not just because growth was weak but because of a host of structural problems in the labor market, reflected in more unfilled jobs even as unemployment was increasing. This mismatch was noted in a speech by Narayana Kocherlakota, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis:

“Firms have jobs, but can’t find appropriate workers. The workers want to work, but can’t find appropriate jobs. There are many possible sources of mismatch—geography, skills, demography . . . It is hard to see how the Fed can do much to solve this problem . . . the Fed does not have the means to transform construction workers into manufacturing workers.”

Who won the fight?

Four years later, which camp turned out to be right? The preponderance of the evidence points to a cyclical explanation, as even Kocherlakota now acknowledges.

Various measures of mismatch have returned to normal levels. For example, in the United States, the mismatch between job openings and unemployment increased in the early years of the Great Recession, reflecting higher vacancies in some segments of the economy and increased unemployment in others, but has since declined.

Another measure of mismatch is the unemployment rate dispersion across U.S. states. This also increased in 2009–10, suggesting that unemployment in some states was far worse than in others. However, this dispersion has since subsided to precrisis levels (see Chart 2). Whether labor force participation will recover remains to be seen.

For other countries, the evidence of mismatch is less clear cut, but the consensus is that cyclical factors are the predominant cause of high unemployment.

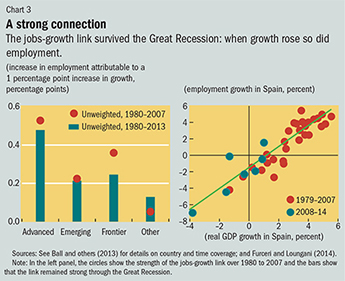

The evidence also belies the prediction by the structuralist camp that a return to growth alone would not lower unemployment. The link between jobs and growth remained robust over the course of the Great Recession, not just in OECD countries but elsewhere as well (see Chart 3, left panel). The chart shows the strength of the link between employment and growth for four groups of economies, which remained essentially unaltered during the Great Recession.

The experience of individual countries confirms this broad picture. For example, Spain’s unemployment dynamics following the Great Recession could have been predicted by the historical relationship between unemployment and growth (see Chart 3, right panel).

Did governments help?

To their credit, most countries mounted a strong policy response in 2008–09 to try to minimize the impact of the crisis on unemployment. Initially, governments moved quickly to use monetary policy to stimulate the demand for products and services—and therefore workers—by lowering official (“policy”) interest rates and, in many cases, bailed out financial institutions. Governments also provided fiscal stimulus, some of it coordinated through the Group of 20 advanced and emerging market economies (G20).

Some countries, such as Germany, also tried to spread the pain of lower demand through work sharing rather than layoffs. The United States and some other countries extended the duration of unemployment benefits. This lowered the social costs of unemployment, apparently without discouraging the unemployed from looking for work.

As unemployment rose, those in the cyclical camp believe, these steps forestalled the kinds of economic consequence the global economy suffered during the Great Depression of the 1930s. It is easy to write off such fears as overblown given what we know today, but that was not so at the time. Governments deserve credit for this prompt and vigorous initial policy response.

A turning point

Around mid-2010, some governments became concerned about the buildup in public debt—attributable in large part to the decline in tax revenues because of the recession and financial sector bailouts—and started to reverse course on their fiscal policy (see box).

The IMF and fiscal consolidation

The 2010 reversal of fiscal policy, with policymakers hitting the brakes on crisis-related spending, received the IMF’s blessing—but not because it believed in “expansionary austerity,” which considers fiscal consolidation good for growth under some circumstances. To the contrary, the IMF’s own research showed that

- fiscal consolidation would be contractionary—that is, it would lower output and raise unemployment; the IMF, in addition, investigated whether its staff was using the right “fiscal multipliers” (that is, whether this contractionary impact of fiscal consolidation was being measured correctly);

- in the past, fiscal consolidation worsened inequality in both advanced and emerging market economies (see “Painful Medicine,” in the September 2011 F&D); and

- during previous global recoveries, fiscal and monetary policies had pushed in the same direction to support recovery.

In light of these findings, the IMF cautioned against cutting back on fiscal stimulus too soon, which risked derailing the budding recovery, and recommended only moderate and measured withdrawal barring acute financing constraints. The design of IMF programs took into account how consolidation would affect the poor and Managing Director Christine Lagarde defended the decision to move to measured consolidation as “the right call to make,” given the growth forecasts available in 2010.

While countries tightened fiscal policy, they further eased monetary policy. In the United States, Charles Evans, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, made a strong case in September 2011 for further easing:

“Imagine that inflation was running at 5 percent against our inflation objective of 2 percent . . . any central banker worth their salt . . . would be acting as if their hair was on fire. We should be similarly energized about improving conditions in the labor market . . . if 5 percent inflation would have our hair on fire, so should 9 percent unemployment.”

His push led to the so-called Evans Rule, an explicit commitment in 2012 by the Federal Reserve to keep its policy interest rates essentially at zero “as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6 1/2 percent” and inflation targets are met. That same year, Mario Draghi, president of the European Central Bank (ECB), pledged to do “whatever it takes” to save the euro.

What’s next?

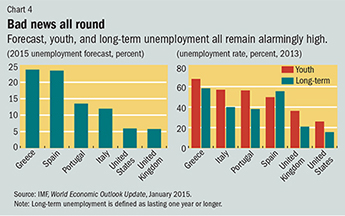

Unemployment is still high in many countries in Europe—alarmingly so in Greece and Spain—and forecasts for 2015 do not project much improvement (see Chart 4, left panel). Long-term unemployment is still high—even in the United Kingdom and the United States, where the overall unemployment rate has fallen—and youth unemployment is high in Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain (see Chart 4, right panel).

Evidence from an IMF study suggests that 50 to 70 percent of the increase in youth unemployment stems from feeble growth. The study, therefore, recommends that “the policy priority should be to boost aggregate demand in the euro area, especially through a strong accommodative monetary policy stance that complements the implementation of needed structural reforms.” (See “Jobless in Europe” in this issue of F&D.)

Encouragingly, the ECB is doing much to support demand: in January 2015, it announced significant further easing of monetary policy. Regarding fiscal policy, steps have been taken to boost growth through public infrastructure projects—cross-border investment in transportation, communications, and energy networks.

Increasingly, these measures to boost demand are accompanied by structural reforms to address economies’ weaknesses that predate the Great Recession. In addition to steps toward a banking union to foster the flow of credit, reforms at the country level include opening up product and services markets such as for energy, streamlining regulatory burdens, and deepening capital markets.

Countries are also trying to tackle the problem of dual labor markets, in which some workers have permanent contracts with strong employment protection while others, often young people, are hired on temporary contracts and receive little protection or training. Italy for instance, has passed a law that authorizes a new kind of labor contract with employment protection that increases gradually with tenure, which should motivate employers to take a chance on younger workers.

Evidence from OECD economies suggests that the response of long-term unemployment to growth is much more muted than that of unemployment overall. Therefore, more targeted policies may be needed to help the long-term unemployed. Katz and others (2014) recommend that governments focus on providing unemployment benefits and training to the long-term unemployed in the depths of a downturn but move toward more aggressive use of active labor market policies such as job search assistance as the labor market tightens in a recovery. People unemployed for a long time may also have trouble keeping a job when they do find one, and there is some evidence that financial incentives can help them do so.

The costs of unemployment are high. Many people who are laid off experience persistent loss in income—even after they eventually find a job—and health problems, their families suffer, and social cohesion breaks down. During the Great Recession, unemployment—and the associated costs—would have been much worse without quick government deployment of monetary and fiscal policies to contain the rise. Bringing down high unemployment in the euro area calls for continued support from monetary policy and fiscal policy that is as growth friendly as possible. ■

Prakash Loungani is an Advisor in the IMF’s Research Department and heads the IMF’s Jobs and Growth project.

References

Ball, Laurence, Davide Furceri, Daniel Leigh, and Prakash Loungani, 2013, “Does One Law Fit All? Cross-Country Evidence on Okun’s Law,” New School talk, September 10.

Draghi, Mario, 2012, speech delivered at the Global Investment Conference, London, July 26.

Evans, Charles, 2011, “The Fed’s Dual Mandate: Responsibilities and Challenges Facing U.S. Monetary Policy,” speech delivered at the European Economics and Financial Centre, London, United Kingdom, September 7.

Furceri, Davide, and Prakash Loungani, 2014, “Growth: An Essential Part of the Cure for Unemployment,” iMFdirect blog, November 19.

Katz, Lawrence F., Kory Kroft, Fabian Lange, and Matthew Notowidigo, 2014, “Addressing Long-Term Unemployment in the Aftermath of the Great Recession,” Vox, December 3.

Kocerlakota, Narayana, 2010, “Inside the FOMC,” speech delivered in Marquette, Michigan, August 17.

Krugman, Paul, 2011, “The Fatalist Temptation,” New York Times blog, July 9.

Ledbetter, James, 2010, “Strucs vs. Cycs,” Slate, August 24.