Capital Slowdown

Finance & Development, June 2017, Vol. 54, No. 2

M. Ayhan Kose, Franziska Ohnsorge, and Lei Sandy Ye

Investment growth in emerging market and developing economies has been sluggish since 2010

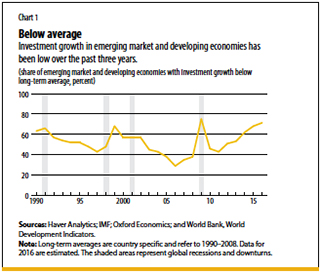

Investment growth in emerging market and developing economies has slowed sharply since the global financial crisis, declining from 10 percent a year in 2010 to less than 3.5 percent in 2016. While there have been signs of revival recently, over the past three years, investment growth, both public and private, has been not only well below its double-digit precrisis average rate but also below its long-term average.

Moreover, the investment weakness has been broad-based. In 2016, investment growth was below its long-term average in more than 60 percent of emerging market and developing economies, the largest number of countries to experience such sluggishness over the past quarter-century except during the 2009 global recession (see Chart 1). The weakness has persisted despite large unmet investment needs and is visible in both private and public components of investment.

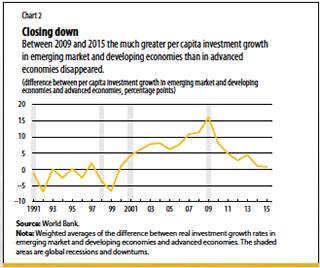

The slowdown has been most pronounced among the large, so-called BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) economies and in commodity exporters. Between 2010 and 2016, investment growth dropped from about 13 percent to about 4 percent in the BRICS and from roughly 7 percent to 0.1 percent in non-BRICS commodity-exporting emerging market and developing economies. China accounted for about one-third of the total investment growth slowdown in these economies during this period and Brazil and Russia for another third. The sustained investment growth slowdown in emerging market and developing economies contrasts with its partial recovery in advanced economies since the global financial crisis. Investment growth in advanced economies averaged 2.1 percent during 2010–15. By 2014, it had returned to its long-term average growth rate, not far below where it was before the crisis.

Why the slowdown?

The investment slowdown reflects a number of factors that offset exceptionally benign financing conditions—including record-low borrowing costs, ample financial market liquidity, and in some countries a surge in domestic private credit to the nonfinancial private sector. However, many headwinds offset the benefits of these historically low financing costs until late 2016, including disappointing economic activity and weak growth prospects and a severe decline in export prices vis-à-vis import prices (that is, a worsening in terms of trade) for commodity exporters, slowing and volatile capital flows, rapid accumulation of private debt, and bouts of policy uncertainty in troubled major economies.

We estimated the relative importance of these domestic and external factors in explaining investment growth.

Adverse factors over the medium term: In contrast to advanced economies, slowing output growth accounted for only a small share of the slowdown in the average emerging market or developing economy.

Terms-of-trade shocks were more important for oil exporters; for commodity importers, slowing inflows of foreign direct investment (in which foreigners take an ownership role), as well as private debt burdens and political risk for many emerging market and developing economies, played a large role. For oil exporters, on average, the terms-of-trade shock caused by the oil price decline that began in 2014 accounted for about half of the investment growth slowdown. For the average commodity importer, slowing foreign direct investment inflows accounted for more than half of the slowdown in investment growth.

Private sector debt-to-GDP ratios have unduly affected investment: the benefits of increased availability of financial services (financial deepening) for investment are increasingly outweighed by harmful effects of excess debt. The postcrisis reduction in debt in several commodity-importing emerging market and developing economies has reduced some of these obstacles to investment growth. In contrast, in several non–energy commodity exporters, high private debt has stymied investment. Rising political risk may account for about a tenth of the slowdown in investment growth in emerging market and developing economies since 2011.

Elevated uncertainty: Two forms of global and country-specific uncertainty are a major drag on investment: financial market uncertainty and macroeconomic policy uncertainty. Domestic policy uncertainty holds back investment growth at home; global financial market uncertainty and policy uncertainty, such as in the European Union (especially among emerging market and developing economies in Europe), have weighed on investment more broadly.

Global financial market uncertainty, as measured by the VIX index (which tracks volatility in the US Standard & Poor’s index of 500 stocks), is a key variable for explaining the path of investment in emerging market and developing economies, especially when there has been a sustained increase in the index. For example, a 10 percent increase in the VIX would considerably reduce investment growth (by about 0.6 percentage point within one year) in these economies.

Bouts of policy uncertainty in the European Union, especially during the euro area crisis of 2010–12, spilled over on close economic partners. For example, policy uncertainty increased significantly during the four months ending September 2011 (at the height of the euro area crisis). This type of rapid increase in uncertainty has likely reduced investment, certainly in emerging market and developing economies in Europe and central Asia. In addition to these cross-border-uncertainty spillovers, domestic uncertainty added to investment weakness in major emerging market and developing economies.

Negative spillovers from major economies: Weak growth in the United States and in the euro area has disappointed expectations a number of times over the past seven years. Given the sheer size of these economies and their degree of trade and financial integration with the rest of the world, a slowdown in their growth significantly worsens growth prospects for emerging market and developing economies.

Weak output growth in the United States and the euro area weighed on investment growth in emerging market and developing economies: a 1 percentage point decline in US output growth reduced average output growth over the following year in emerging market and developing economies by about 0.8 percentage point, and a decline of the same amount in euro area output growth did so by about 1.3 percentage points within a year. Investment growth in emerging market and developing economies responded almost twice as strongly (2.1 percentage points) as did output growth.

China’s policy-driven slowdown and rebalancing from investment toward consumption also hurt output growth in emerging market and developing economies. Since China is now the largest trading partner of many emerging market and developing economies, its output and investment growth slowdown has weighed on their growth.

For example, within a year, a 1 percentage point decline in China’s output growth was accompanied by about a 0.5 percentage point decline in output growth in other commodity-importing emerging market and developing economies and a 1 percentage point decline in output growth in emerging market and developing economy commodity exporters. Since much of its investment is resource intensive, China’s rebalancing away from investment has been more harmful for commodity-exporting emerging market and developing economies.

Effect on growth prospects

The postcrisis investment growth slowdown from record highs before the crisis could have lasting implications for long-term growth. By slowing the rate of capital accumulation, a prolonged period of weak investment growth can set back potential output growth in emerging market and developing economies for years. In 2009, there was about a 15 percentage point difference between per capita investment growth in emerging market and developing economies and advanced economies. By 2015, the difference was virtually zero, the lowest it has been since the early 2000s (see Chart 2). Because growth is one of the most powerful ways to reduce poverty, any setbacks to growth also jeopardize global goals for poverty reduction.

In addition to slowing capital accumulation, weak investment growth is associated with slower growth in total factor productivity (the part of economic growth that cannot be explained by increases in labor and capital inputs and reflects technological and efficiency changes). That’s because investment is often critical to the adoption of new, productivity-enhancing technologies. The productivity slowdown was most pronounced in commodity-exporting emerging market and developing economies and in those with the slowest investment growth. Weaker total factor productivity growth is also reflected in slower growth in labor productivity (output per hour worked)—the key driver of long-term real (after inflation) wage growth and household income growth.

Boosting investment

Many emerging market and developing economies have large unmet investment needs (Kose and others 2017). A number of these countries are poorly equipped to keep up with rapid urbanization and changing demands on workers. Investment is also needed to smooth the transition away from growth driven by natural resources (in commodity exporters) or sectors that do not engage in foreign trade (in some commodity importers) toward more sustainable sources of growth.

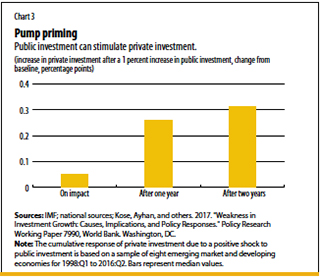

Policymakers can boost investment directly, through public investment, and indirectly, by encouraging private, including foreign direct, investment, and by undertaking measures to improve overall growth prospects and the business climate. Doing so directly through greater public investment in infrastructure and workers would help raise demand in the short term, increase potential output in the long term, and improve the environment for private investment and trade. Public investment would also help close income gaps, as targeted by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and, under the right conditions, has the potential to stimulate private investment (see Chart 3).

Indirectly, macroeconomic policies can encourage productive investment—for example, by ensuring macroeconomic stability and improving short- and long-term growth prospects. More effective use of fiscal and monetary policies designed to counter slowing or declining growth can also promote private investment indirectly by strengthening output growth, especially in commodity-exporting emerging market and developing economies. These policies may be less effective, however, if governments lack resources to increase spending or reduce taxes or if output growth is weak because of a need to adjust to a permanent decline in revenues from commodity exports.

To raise investment growth sustainably, such policies must be buttressed by structural reforms to encourage both domestic private and foreign direct investment. These reforms could span various areas. For example, lower barriers to entry for businesses and smaller start-up costs are associated with higher profits for existing firms and greater benefit from foreign direct investment for domestic investment. Reforms to reduce trade barriers encourage both foreign direct and overall investment. Corporate governance and financial sector reforms improve the allocation of capital across firms and sectors. Stronger property rights encourage corporate and real estate investment. Such policies should be complemented by efforts to foster transparency—that is, better financial reporting methods.

M. AYHAN KOSE is a director, FRANZISKA L. OHNSORGE is a lead economist, and LEI SANDY YE is an economist, all in the Prospects Group of the Development Economics Vice Presidency of the World Bank.

Reference

Kose, Ayhan, and others. 2017. "Weakness in Investment Growth: Causes, Implications, and Policy Responses." Policy Research Working Paper 7990, World Bank. Washington, DC.