Palau is set to introduce a value-added tax in a move next year that will provide a fillip to public finances. This will also set an example of reform that other cash-strapped governments in the Pacific could follow.

Palau’s tourism-dependent economy shrank by almost 10 percent in 2020 as the government sealed the borders to stave off COVID infections. The national budget sank into deficit equal to 11 percent of gross domestic product.

The government could raise an additional 1 percent of GDP in annual revenue when it starts to collect the new taxes, including VAT, known locally as the Palau Goods and Services Tax, approved as part of a wide-ranging reform package in September 2021.

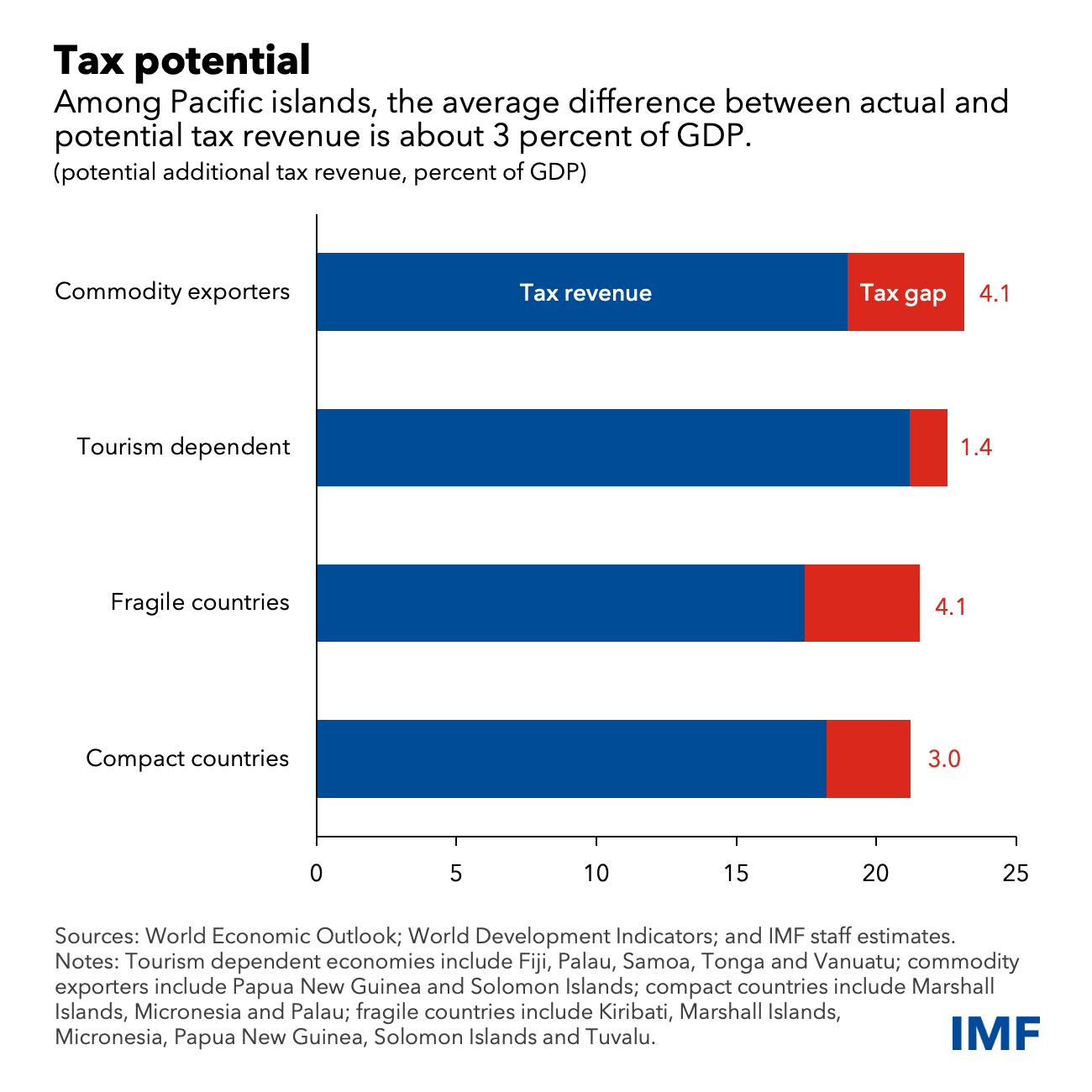

Other Pacific nations could follow Palau’s example. A recent IMF paper shows that the average tax gap—the difference between current and potential tax revenue—is about 3 percent of GDP in the Pacific region.

Closing this gap could play a critical role in creating space for social-development and climate-related spending in a region that faces an existential threat from rising seas and tropical cyclones.

Pacific islands must on average spend an additional 6.3 percent of GDP over the next decade to meet the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and about 3.1 percent to build new climate-resilient infrastructure, IMF staff estimate.

International support on concessional terms, such as through the IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Trust, should play an important part in meeting these spending needs. But the region itself can do more, too.

As a group, the Pacific islands have implemented some major tax reforms and made progress in raising tax revenue in recent years.

Fiji, for instance, invested in technology upgrades at its tax office and a new website that allows taxpayers to register online.

Micronesia made its corporate tax structure more progressive, while Vanuatu increased its VAT rate from 12.5 percent to 15 percent.

But in many cases progress has come through windfall gains, particularly from corporate income taxes. There has been a lack of momentum towards more durable tax-policy and revenue-administration reforms.

Missing momentum

Tax offices are often understaffed, underfunded and work with outdated technology. This makes it a challenge to raise compliance and collect all the taxes that are owed. Policy reforms often languish in legislatures.

Meanwhile, government relief measures to mitigate the impact of the pandemic and higher prices for imported food and fuel following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are piling pressure on public finances.

Well-designed VAT systems can encourage compliance and lift receipts from other types of taxation. However, many Pacific islands do not have yet a VAT system and those that do are not exploiting its full potential.

The gap between the current VAT collection and what could potentially be collected is on average about 50 percent—pointing to significant room for improvement.

All VAT rates in the region are below the world’s average ,and there are widespread exemptions. IMF research suggests there could be significant revenue gains by reforming VAT systems. Key steps should include a focus on a single broad-based VAT rate and increasing VAT rates in some Pacific islands. Improving compliance through better enforcement could also boost collection.

Countries such as Marshall Islands without a VAT should consider adopting one. Given that poor households tend to spend a larger proportion of their current income, VAT implementation should be accompanied by efforts to support the vulnerable and poor through well-targeted fiscal measures.

Beyond VAT, the Pacific islands should make domestic resource mobilization a priority as part of a broader strategy to reduce public debt, restore fiscal space, and finance climate and development spending.

A comprehensive approach, rooted in a medium-term revenue strategy and supported by technical assistance from the IMF and others, could be one of the most effective pathways to tackling daunting structural issues and financing development spending.