|

The Cross-Border Initiative (CBI) comprises a common policy framework developed by fourteen participating countries in Eastern and Southern Africa and the Indian Ocean, with the support of four co-sponsors; the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the European Union, and the African Development Bank. The participants are Burundi, Comoros, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Namibia, Rwanda, Seychelles, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe; Mozambique has also indicated its intention to join. The policy framework aims to facilitate cross-border economic activity by eliminating barriers to the flow of goods, services, labor, and capital, and to help integrate markets by coordinating reform programs in several key structural areas, supported by appropriate macroeconomic policies. The initiative places the responsibility for determining how to implement the agreed policy measures at the national level. The four key elements of the Initiative are:

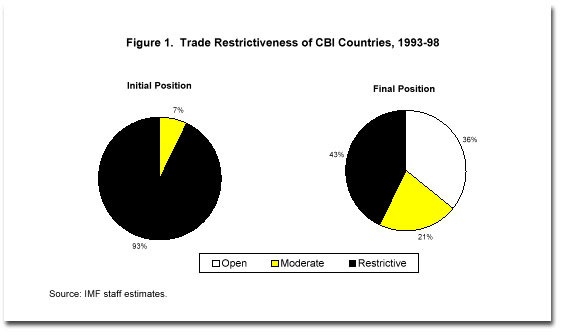

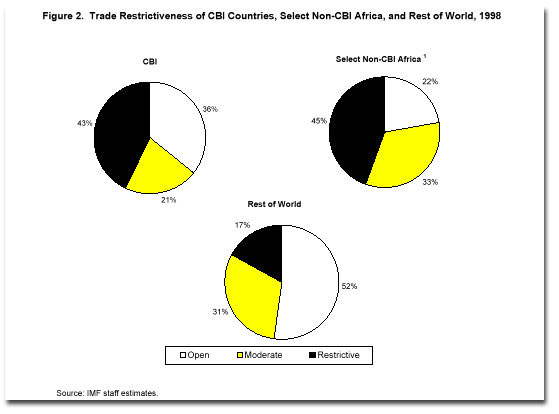

The purpose of this paper is to take stock of the achievements under the CBI in each of the four areas mentioned above. The paper takes into account recent developments through end-December 1998. Regarding the liberalization of foreign exchange systems, most countries had removed restrictions on current account transactions by end-1998. In addition, a handful of countries liberalized substantially capital account transactions while the remaining countries took partial steps to ease such controls, including those affecting equity investments among the participating countries. On the exchange rate regime, most countries met the CBI objective of introducing a flexible exchange rate system within the context of a unified inter-bank foreign exchange market. On trade liberalization and facilitation, significant but uneven progress was achieved. Many of the participating countries made substantial progress toward meeting the CBI targets on tariffs. Although, none of the countries fully eliminated intraregional tariffs, virtually all countries implemented preference margins for other CBI participants ranging between 60—80 percent. Progress on MFN liberalization was mixed; (i) three countries met the target of lowering the maximum tariff rate to 20—25 percent; (ii) six countries met the target of reducing the number of nonzero tariff bands to no more than three; and (iii) three countries where data are available, met the target of reducing their weighted average tariff rates to no more than 15 percent. Nevertheless, tariff exemptions remained widespread, including for imports by governments, parastatals, nongovernmental organizations, and for goods related to foreign-financed projects and those under the various investment codes. The pace of trade reform reflected, in part, concerns on the potential adverse impact on fiscal revenue. Notable progress was achieved in reducing nontariff barriers to imports. Most countries eliminated import quotas and bans, as well as import licensing requirements. Moreover, the monopoly power previously exercised by state marketing boards or state controlled enterprises in regard to exporting, importing, and price setting was significantly reduced in most of the countries. Although export duties and export marketing monopolies remained in place in about half the countries, only a few countries continued to maintain export restrictions. Finally, substantial progress was also achieved in some key areas of trade facilitation, including implementing the harmonization of road transit charges, and the introduction of the Road Customs Transit Document and of a single goods customs declaration form. Good progress was made in reforming the domestic financial sectors to improve their efficiency. Most countries moved to the use of indirect monetary instruments to control monetary aggregates, and administered interest rates were phased out and replaced with market-based mechanisms. Increased attention was devoted to strengthening the powers of central banks to enforce prudential regulations and to provide autonomy in conducting monetary policy. All CBI countries had either adopted or were in the process of adopting Basle capital adequacy standards, and several countries required that the capital ratio be above the minimum 8 percent of risk-weighted assets. In addition, most of the countries had prudential limits on connected/single borrower transactions, as well as on single/aggregate foreign exchange exposures. There was a substantial increase in the number of banks in some countries, including a significant presence of foreign owned banks, but in other countries, the degree of competition in financial markets was still limited to a few operators. Progress was made in the area of investment deregulation. There was substantial simplification of approval procedures (particularly through the establishment of a one-stop investment approval authority). The publication of investment codes was completed by ten participants, and substantive progress made in the remaining countries. However, with the exception of a few countries, most of the investment codes included some form of tariff exemptions. There was slow progress in concluding double taxation agreements, in the cross-listing of stocks, and in facilitating labor mobility (visa protocol, residence/work permits, and short-term entry permits). I. Introduction1. As described in earlier papers1, the Cross-Border Initiative (CBI) comprises a common policy framework developed by fourteen participating countries in Eastern and Southern Africa and the Indian Ocean2, with the support of four co-sponsors—the Fund, the World Bank, the European Union (EU), and the African Development Bank. The policy framework aims to facilitate cross-border activity by eliminating barriers to cross-border flows of goods, services, labor, and capital, as well as to integrate markets through a coordination of reform programs in the areas of trade, exchange systems, domestic banking and payment systems, and investment regulations, supported by appropriate macroeconomic policies. The CBI has avoided the creation of new institutions, placing responsibility at the national level for the design and implementation of measures to support the agreed policy framework. 2. To this end, a set of "core" measures were articulated in a Concept Paper3, which was adopted at the First CBI Ministerial Meeting in Uganda in August 1993 (Box 1). A Second Ministerial Meeting, held in Mauritius in March 1995, endorsed a "Road Map" for further trade liberalization that included the elimination of tariffs on intraregional trade and the convergence of external tariffs to a trade-weighted average of 15 percent, both by October 1998. At the Third Ministerial Meeting, held in Zimbabwe in February 1998, the participating countries decided to continue and broaden the CBI, and agreed that the future focus should emphasize investment facilitation issues, and the harmonization of national and regional policies toward a conducive environment for efficient investment and trade flows. 4 3. Under the CBI, each participating country was expected to: (i) create a Technical Working Group (TWG) comprised of representatives of the public and private sectors that would identify and report on the main impediments to the cross-border activities outlined in the Box, and would suggest a common program of action to be implemented at the national level; (ii) establish a Policy Implementation Committee (PIC), comprised of officials with the authority to design and implement a specific program of policy measures5; and (iii) complete a Letter of CBI Policy (LCBIP) specifying the steps that the country would take to implement the various measures, including regulatory changes and a timetable which would be endorsed by the co-sponsors. 6 4. As one of the co-sponsors, the Fund's role was to ensure that each LCBIP was consistent with progress toward a stable macroeconomic framework. The CBI objectives and the schedule of implementation of the various measures have been featured in staff discussions in the context of Article IV consultations and use of Fund resources, and have been taken into account in considering technical assistance requests. For countries undertaking structural adjustment in the context of Fund-supported programs, actions included in the LCBIPs have been built in, and coordinated with, the adjustment program. The CBI has also been featured in staff discussions with nonparticipating countries to apprise them of emerging policy trends with wider implications. 5. The purpose of this paper is to take stock of the achievements of the CBI since its inception in 1993. It is, of course, important to mention that measures in areas such as improving financial intermediation were underway before the CBI began and were undertaken for domestic reasons rather than considerations regarding regional cooperation and harmonization. Section II describes progress in implementing the measures specified in the four areas of the CBI policy framework as of December 1998—foreign exchange systems, trade regimes, domestic banking and payments systems, and investment regulations. Finally, Section III discusses the remaining agenda and the issues to be addressed.

A. Liberalization of Foreign Exchange Systems Developments 6. Under the CBI framework, participants are expected to eliminate exchange restrictions on current account transactions in a nondiscriminatory manner and to relax certain types of capital transactions. The liberalization of the capital account referred principally to transactions associated with long-term, non-debt-creating, foreign direct investments (FDI) rather than to short-term capital. The main focus of the reform was to improve the regulatory environment for investments, both domestic and foreign; progressively harmonize investment incentives; and encourage investment in regional equity markets (see Section D below). In light of the fragility of the domestic financial system (elements of which were to be addressed within the Initiative; see Section C), the liberalization of short-term capital inflows was not perceived to be a priority. In regard to foreign exchange markets, the objective was to establish unified, interbank spot-exchange markets no later than 1996. Such markets would, in turn, set the stage for more diversified operations, including forward cover, and liberalization of foreign currency accounts. 7. With regard to the removal of exchange restrictions on current account transactions, 12 of the 14 CBI countries have accepted the obligations under Article VIII, sections 2, 3, and 4 as of December 1998 (compared with only two in 1993) (Table 1)7. Regarding the capital account, Kenya, Malawi, Mauritius, Uganda, and Zambia have substantially liberalized capital account transactions, while Comoros and Madagascar have taken steps to ease controls, including on the repatriation of portfolio outflows. Tanzania and Zimbabwe also took steps in the latter regard. 8. Exchange arrangements vary widely, with 9 participating countries maintaining a floating exchange rate system in the context of unified interbank exchange markets (Tables 2 and 3)8. Controls on foreign currency accounts for residents and foreign entities have been lifted, with the exception of Burundi, Comoros, Namibia, Seychelles, Swaziland, and Zimbabwe. Finally, although some progress has been made over the last three years in easing foreign exchange repatriation and surrender requirements, most countries continue to impose such controls (Table 4). Competition in foreign exchange markets has also been enhanced with the licensing of nonbank foreign exchange bureaus in nine countries. Forward cover through commercial banks and other authorized dealers is available in nine countries. In addition, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda (the East African Cooperation (EAC) countries) have agreed that their respective currencies be fully accepted within the EAC countries, and that the currencies be quoted by banks and foreign exchange bureaus. B. Trade Liberalization and Facilitation Developments 9. The CBI framework called for a coordinated and time-bound reduction of trade barriers at the regional level, and with third countries on an MFN basis. The specifics of the trade reform agenda and the timetable for implementation included: (i) effective October 1995, increasing from 60 percent to 70 percent the intraregional tariff preference for countries that had not yet done so; (ii) elimination of tariffs on intraregional trade by October 1998, with an increase in the preference rate to 80 percent by October 1996 and to 90 percent by 1997; and (iii) a harmonized external tariff to be adopted by October 1998 consisting of no more than three nonzero bands, a trade weighted average tariff rate of no more than 15 percent, and a maximum rate of 20—25 percent9. With regard to nontariff barriers (NTBs), countries were expected to dismantle import licensing requirements and similar NTBs on an MFN basis, except for a short "negative list" for noneconomic reasons such as security, health, and environment. Quantitative restrictions on exports to all countries were to be eliminated, except for a small negative list for the same noneconomic reasons. 10. By end-December 1998, many of the participating CBI countries had either met or made substantial progress toward meeting CBI targets for trade liberalization (Tables 5 and 6). Significant progress on tariff reduction on intraregional trade was achieved. Although, none of the countries met the target for eliminating intraregional tariffs by end-December 1998, Kenya, Madagascar, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zimbabwe, had implemented an 80 percent preference margin, while Burundi, Comoros, Malawi, Mauritius, Rwanda, and Zambia had increased the preference margin to 60—70 percent. Moreover, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda have indicated a desire to accelerate tariff reductions on trade between them, in the context of the EAC Agreement. Namibia and Swaziland could not change their preference margins because they are members of the Southern African Customs Union (SACU). Seychelles has not made any progress on increasing the preference margin. 11. Regarding the reduction of the maximum tariff rate, Kenya, Uganda, and Zambia met the CBI target of 20—25 percent by end-December 1998 10. In addition, Madagascar, Malawi, and Tanzania reduced their maximum rates to 30 percent, while Comoros and Rwanda lowered theirs to 40 percent. Although some reductions have taken place in the remaining six countries, the maximum rates remain high in Mauritius, Namibia, and Swaziland (in the range of 70—80 percent); and substantially higher in Burundi and Zimbabwe (100 percent), and Seychelles (200 percent). 12. Comoros, Kenya, Madagascar, Rwanda, Uganda, and Zambia met the target of reducing the number of nonzero bands to no more than three, by end-December 1998—Uganda's two tariff bands went beyond the target. Burundi, Malawi, and Tanzania had 4—5 tariff bands, and the least amount of progress was recorded in the cases of Mauritius, Seychelles, and Zimbabwe with 8, 9, and 17 bands, respectively, and the SACU countries which continued to have multiple tariff bands. 13. Information on the weighted average tariff rate is not available for all countries. Among the countries with such information, the CBI target of an average tariff rate of no more than 15 percent was met with substantial margins in Kenya, Uganda, and Zambia. Using the more widely available unweighted average tariff rate, six countries (Malawi, Namibia, Rwanda, Swaziland, Uganda, and Zambia) have averages that are either around or below 15 percent. Kenya and Madagascar had unweighted average rates of about 18 percent, and the rest of the countries had unweighted average rates ranging from 21.8 percent (Tanzania) to 35 percent (Burundi). Limited progress was made in reducing other duties and charges (ODCs) and in amalgamating them into the basic tariff structure, mainly because of revenue concerns. Malawi, Seychelles, Tanzania, and Zambia met the CBI objective, while Burundi, Comoros, Namibia, Rwanda, Uganda, and Zimbabwe had ODCs below 15 percent, and Madagascar and Mauritius had ODCs of up to 40 percent and 400 percent, respectively. 14. Although notable progress was achieved in reducing import NTBs, particularly those related to bans, quotas, and licensing requirements, the record on dismantling state monopolies and eliminating discriminatory taxes and reducing tariff exemptions has been mixed (Table 7 and 8). The CBI countries have eliminated all import quotas and bans, with the exception of Namibia (which has quotas for imports of used cars and clothing, and seasonal bans on some agricultural products), Uganda (which has a ban on cigarettes that is expected to be eliminated by July 1999), Seychelles (which has semiannual quotas on all imports) and Swaziland (which maintains seasonal bans on some agricultural products). Import licensing requirements have been eliminated in most CBI countries, with the exception of Namibia, Seychelles, and Zimbabwe. The monopoly power previously exercised by state marketing boards or state controlled enterprises with regard to exporting, importing, and price setting was significantly reduced in all countries with the exception of Comoros, Mauritius, Namibia, Seychelles, Swaziland, and Tanzania. Similarly, progress was mixed in eliminating discriminatory higher rates of excise duty and/or value-added tax on certain imports which remain in half of the CBI countries (Burundi, Kenya, Mauritius, Seychelles, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia). Tariff exemptions remain widespread, including for imports by governments, parastatals, nongovernmental organizations, and for goods related to foreign-financed projects and those under the various investment codes. 15. Substantial progress was achieved in reducing impediments to exports (Table 9). By end-December 1998, only Zambia and Zimbabwe maintained export bans and quotas, respectively, while export licenses were required in only three countries (Kenya, Namibia, and Zimbabwe). Export duties remained in place in Burundi, Comoros, Rwanda, Swaziland, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe, while Burundi, Namibia, Seychelles, Swaziland, and Zimbabwe still maintained marketing monopolies. 16. Substantial progress was achieved in some key areas of trade facilitation. With the exception of the SACU countries (Namibia and Swaziland) and the island economies, the rest of the CBI countries implemented the harmonization of road transit charges, and introduced the Road Customs Transit Document (Table 10)11. In addition, a single goods customs declaration form was introduced by most countries, except in Burundi, Malawi, and Rwanda, where information is not available. In contrast, however, no country had yet introduced a bond guarantee scheme by the end of the CBI period. Assessment of progress 17. The extent of trade liberalization achieved in the CBI countries can be assessed using an index of aggregate trade policy restrictiveness.12 Under the CBI, considerable progress has been made in trade reforms, mainly in the context of adjustment programs supported by the Fund and the World Bank. Five countries moved to open trade regimes, compared to zero at the inception of the initiative; another three countries had moderately restrictive trade regimes, the same number as at the beginning of the initiative; and the remaining six countries continued to have relatively restrictive trade regimes (Figure 1 and Table 11). 18. Based on the index, the most ambitious reformers were Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Rwanda, Uganda, and Zambia, as they reduced their restrictiveness ratings by 4—5 points and achieved open trade regimes (except Kenya which moved from the restrictive to the moderate category). In contrast, Burundi, Comoros, Seychelles, and Zimbabwe made no progress in trade liberalization; moreover, Seychelles and Zimbabwe continued to have a rating of "10" on the index.  19. As a group, the CBI countries reduced their rating on the index by an average of 2.4 points compared to 1.7 for a select group of non-CBI African countries.13 As a result, although the CBI countries had more restrictive trade regimes at the beginning of the Initiative, by end-1998 their trade regimes were, on average, less restrictive (5.9) than those of the select group of non-CBI countries (6.2). However, the CBI countries still remain, on average, markedly more restrictive than countries in other regions. While 43 percent of the CBI countries would be classified as having highly restrictive trade regimes, only 17 percent of the economies of the rest of world (excluding non-CBI African countries) would be classified as highly restrictive (Figure 2). Similarly, only 36 percent of the CBI countries would be classified as open compared with 52 percent for the rest of the world. Of course, the rating for the rest of world masks a wide dispersion among the various regions of the world, with industrialized countries as a group having the lowest rating of 4 and the Middle Eastern countries having the highest rating of 5.5, compared with 5.9 for CBI countries.14 It is important to note that good practice countries (Chile, Colombia, New Zealand, and Singapore) have a rating of 1.5, and that Uganda and Zambia, with ratings of 2, are very near this level.  Factors influencing achievement of CBI trade reform objectives 20. Several reasons have been cited for the delay in implementing trade policy reforms. These included: civil unrest (Burundi, Comoros and Rwanda); the concern about potential adverse impact of trade reform on government revenues (Comoros, Tanzania and Zimbabwe) and hence on macroeconomic stability; and membership in other regional trading arrangements (RTAs). The fiscal impact of trade reform depends on the nature of the reforms introduced and the specific circumstances of the country.15 In order to offset any possible adverse effect on revenues, the reduction in tariffs should be accompanied by a tariffication of NTBs on imports and exports, and the elimination of tariff exemptions. However, even in those circumstances where trade liberalization might lead to a short-term loss in revenues, the appropriate response should be to adopt offsetting measures—if on the revenue side preferably by less-distorting and more broad-based taxes that are applied equally to both imports and domestic production. 21. The excessive number of RTAs which the CBI countries are members may indeed have interfered with the pace of trade liberalization. As shown in Figure 3 and Table 12, the CBI countries are members of five different RTAs: the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), EAC, IOC, SACU, and the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC). These countries are faced with conflicting obligations, different and uncoordinated strategies, inconsistent external liberalization goals, and different and conflicting rules and administrative procedures. For example, under the COMESA Treaty, 80 percent preferences were to have been provided by the member states to each other by 1998 and 100 percent by 2000. In contrast, under the more accelerated CBI framework, the complete elimination of intra-CBI tariffs was envisaged to take place by end-October 1998. As for the SADC, intraregional preferences are also envisaged, but over eight years beginning in 2000. C. Reform of the Domestic Financial Sector Developments 22. The development of a sound financial sector and efficient payment systems are viewed as essential for increasing cross-border flows and market access. To ensure the soundness of financial institutions, the CBI framework called for intensified efforts to improve prudential and supervisory capacity of central banks so as to encourage development of the commercial banking sector and other financial institutions, and to strengthen the domestic payments system. Additional measures included developing foreign trade financing instruments and establishing correspondent banking relationships within the region. 23. At the commencement of the Initiative, virtually all CBI countries relied on bank-by-bank credit ceilings and administered interest rates as key instruments of monetary policy. Government interference was prevalent, through directed credit allocations, heavy borrowing from central banks to finance large fiscal deficits, and maintenance of negative real interest rates. With respect to the institutional structure, a proper legal framework for the independence of central banks was largely absent, entry by domestic and foreign commercial banks was restricted and led to concentrated ownership structures, and regulation and supervision were inadequate to ensure the soundness of financial institutions.  24. Despite the variety of problems, there has been good progress in improving the efficiency of the financial system. In the banking system, direct monetary instruments in the form of individual bank credit ceilings and selective credit controls have been phased out in all countries except Comoros; most countries now use indirect monetary instruments such as open market operations, changes in liquidity requirements, and standing discount facilities (Table 13).16 Administered interest rates have been phased out and replaced with market-based mechanisms in almost all countries except Comoros and Seychelles.17 25. Financial market developments can also be gauged by the presence of active primary and secondary markets for public debt instruments, an interbank money market, and a stock exchange. Most CBI countries, with the exception of Comoros, Rwanda, and possibly Burundi have fairly active primary markets for government and central bank securities with weekly auctions, and/or tap sales between auctions. The existence of secondary markets is more limited, with active markets being present only in Kenya, Malawi, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Secondary markets have been slow to develop, owing in part to the existence of high liquidity requirements, the lack of infrastructure and capacity, as well as lingering doubts about the soundness of some banks. The latter factor has confined active interbank markets to Kenya, Malawi, Mauritius, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Stock exchanges exist in several countries, but it could be argued that only the stock exchanges in Kenya, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe are relatively active. 26. Attention has also been devoted to central banks' powers to enforce prudential regulations. To this end, legislation was enacted or revised during 1993—98 in Madagascar, Namibia, Seychelles, Swaziland, Uganda, and Zambia (Table 14). In Comoros and Zimbabwe, the supervisory and regulatory role continues to be shared by the government and the central bank. In principle, central banks have full autonomy in most countries, except in Comoros, Kenya, Tanzania, and Zambia, where autonomy is partial.18 27. Roughly half the CBI countries have either fully or substantially implemented financial sector reform programs. An evaluation of the development of foreign trade instruments and the removal of impediments to entry indicate that considerable progress has also been achieved in the majority of countries. The increased focus on financial sector reform issues has also coincided with an expansion of financial markets in most of the countries. Thus, the number of commercial banks has increased to more than 50 in Kenya; 21 in Zambia; 20 in Uganda and 18 in Tanzania. At the same time, all countries with the exception of Comoros and Malawi have foreign banks operating in their countries; and Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania, and Uganda have taken measures to reduce government ownership or privatize state-owned banks and to review existing licensing procedures before licensing additional new banks. The payment system appears to be satisfactory in ten of the participating countries although efficiency is high in only a few (Mauritius, Namibia, and Swaziland). Assessment of progress 28. Despite recent progress in several areas, the degree of competition in financial markets in a number of countries remains limited to a few operators, and there is only a thin supply of financial instruments. The market for treasury and central bank bills remains narrow in most of the participating countries, to the extent that the frequent reason attributed to the lack of secondary markets in public debt is the absence of a sufficient amount of outstanding public paper. In this context, changes in reserve and liquidity ratios have been extensively used as the preferred monetary instrument. Such uses (together with the high level of nonperforming loans) are often cited as contributing to the wide spreads between deposit and lending rates. 29. Supervisory practices have improved significantly in most of the CBI countries. All CBI countries have either adopted or are in the process of adopting the Basle standard for capital adequacy requirement of 8 percent; and in several countries the capital ratio is above the minimum requirement. Most of the countries have prudential limits on connected/single borrower transactions, as well as on single/aggregate foreign exchange exposures. D. Reform of Investment Regulations 30. Another major objective of the CBI involved reforming the regulatory environment for direct investments, and the progressive harmonization of the structure of investment incentives. In regard to the regulatory environment, participating countries agreed to simplify and codify all investment-related regulatory provisions into a single published document that would be widely available; establish one-stop investment centers that would process all applications between 45 days and 60 days; and grant automatic approval in the absence of objections at the end of that period. Other specific measures called for participants to conclude avoidance of double taxation agreements on a bilateral basis; authorize the cross-listing of stocks from other exchanges in the region; and expedite the processing of residence and work permits, and relax visa requirements for investors. In addition, participating countries were expected to become members of the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency, and where necessary, of bilateral investment guarantee agencies such as Overseas Private Investment Corporation. The ratification of a suitable amended form of the Multilateral Industrial Enterprise Charter was also encouraged.19 31. Overall progress in the area of investment deregulation has been mixed. There has been almost full liberalization of approval procedures (in particular establishing a one-stop investment approval authority), and the publication of investment codes has been completed by 10 participants, and the remaining countries have made substantive progress (Table 15). However, with the exception of a few countries, most of the investment codes include tariff exemptions. With regard to the statute of limitation, only 6 participants have fully implemented it. There has also been slow progress with regard to double taxation agreements and cross-listing of stocks. 32. Overall progress in regard to the facilitation of labor market issues (visa protocol, residence/work permits, and short-term entry permits) has also been mixed. Most of the non-island economies have taken action on short-term entry permits for border residents, while the EAC countries—Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda—no longer require visas for their citizens to travel between their countries. There has been little progress in the processing of residence and work permits except for Kenya, Namibia, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia. III. The Remaining Agenda33. In the context of a gradual return to macroeconomic stability, good progress has been achieved in most of the CBI countries in the liberalization of exchange systems over the last few years. This is reflected in the widespread elimination of restrictions on external current transactions, the shift towards market-based exchange rates, and the move (mainly in respect of inflows) towards liberalizing external capital transactions related largely to FDI. The movement towards liberalization, moreover, has reduced reliance on direct controls, and correspondingly increased the role of macroeconomic policies. In particular, macroeconomic policies have become the key instruments in promoting exchange rate stability and containing inflationary pressures. Some countries, however, still need to remove the remaining restrictions on current account transactions. To strengthen investor confidence and the export environment there is also the need to further liberalize capital account transactions on FDI and to liberalize foreign exchange repatriation and surrender requirements. 34. Although some of the CBI countries have made significant progress in trade liberalization going well beyond the CBI objectives to achieve open trade regimes, others continue to have either moderately or highly restrictive trade regimes. Ideally, the countries classified as having moderately to highly restrictive trade regimes need to move to open trade regimes, say, over the next three years. Moreover, countries should continue to persevere with trade reform by lowering their maximum tariff rates to no more than 15 percent (in line with the current maximum rate for Uganda), and reducing the number of nonzero tariff bands to 2 or 3 and their unweighted average tariff rates to no more than 10 percent over the medium term. 35. The continuing existence of other duties and charges outside the basic tariff structure needs to be eliminated. The amalgamation of these charges into the tariff structure would reduce its complexity and improve its transparency and efficiency. With regard to NTBs, much remains to be done, especially in the areas of state monopolies and discriminatory taxes. Given that NTBs are the most distortionary aspects of a trade regime, the future agenda should focus attention on eliminating them as a priority. By making the trade regimes more transparent and less distorted, such an agenda would help make these economies more efficient and competitive. More determined efforts will be needed to eliminate or reduce sharply tariff exemptions. This would serve the purpose of strengthening the fiscal position and introducing more transparency into the trade regimes. 36. The difficulties caused by overlapping RTAs needs to be addressed. Ideally, while trade liberalization should be undertaken on an MFN basis, the extension of tariff preferences to other members of RTAs is likely to enhance trade creation and lessen trade diversion, if accompanied by liberalizing on an MFN basis. In this light, it would be important that the overlapping regional trade arrangements in Eastern and Southern Africa (see Annex I) harmonize the various goals and objectives of the different RTAs, coordinate them more efficiently, and make their objectives more internally consistent so as to (i) avoid negating some of the potential gains from regionalism and undermining the potential improvement in the investment climate that arise from a larger market and improved transparency; (ii) introduce common and simple (rather than conflicting) rules of origin into the trading process; (iii) prevent costly duplication of administrative effort; and (iv) reinforce the reform momentum by consolidating the political capital needed to pursue reforms. CBI participants should make every effort to achieve these goals and accelerate the ongoing efforts at trade facilitation. 37. As a practical matter, rationalizing the current multiple RTAs would be facilitated by accelerating reduction of external tariffs on an MFN basis and removing NTBs. Such an action by one country, or group of countries, could increase the pressure on others to follow suit to prevent intraregional trade and investment from being diverted away from them. In addition, more frequent contacts between all the countries in the region might provide a forum for discussion on adopting a common set of objectives, adopting common rules and regulations and reducing administrative complexity, and for resolving policy disagreements. For example, it would be useful to explore the possibility of inviting COMESA and SADC to join the CBI Steering Committee. Rationalization of the multiple RTAs would enlarge markets, improve transparency, and reduce administrative costs, thus providing a better climate for trade and investment. 38. Despite recent progress in several areas, much work also remains to be done to develop the financial systems to achieve the objectives of the CBI. The authorities need to work toward increasing competition in the financial system by accelerating the pace of privatization of banks, in a transparent manner, and by granting further autonomy to central banks—legally and in practice. Further, macroeconomic stability and the resulting lower inflation rate will ensure that real interest rates are positive and help raise financial savings, and thus the development of money and capital markets. There is also the need to strengthen regulation and supervision to help achieve financial system soundness, which is an important element for macroeconomic stability. The introduction of a transparent safety net, such as a well defined and limited deposit insurance scheme, rather than reliance on blanket government guarantees, would help increase market discipline. It should be pointed out that the prevalence of state-owned banks makes it hard to credibly refuse to bail out such banks in case of failure. 39. Increased investment (both domestic and foreign) in participating countries is crucial for real per capita economic growth and diversification. As mentioned earlier, the Third Ministerial Meeting held in Zimbabwe (February 1998) requested the co-sponsors to prepare a Road Map for Investment Facilitation to be discussed at the Fourth Ministerial Meeting to be held in 1999. The paper outlining this road map, which has now been finalized by the co-sponsors, indicates that while there has been an upturn in the average real per capita growth in recent years, growth in sub-Saharan Africa and the CBI countries needs to be raised and diversified to ensure a significant improvement in living standards in the near future. To this end, gross investment in the CBI countries needs to be increased to at least 25 percent of GDP, as suggested by the Global Coalition for Africa. Foreign direct investment, which had increased only marginally compared to other developing countries, should be allowed to play an important role in this process. The main lessons of experience drawn by the Paper are that investor confidence is linked not only to the perception of the robustness of reforms, but also to their consistent implementation over time; that reform efforts (which usually take a long time) have not been consistent and sustained enough to regain investor confidence; and that a concerted effort is needed, over an extended period, to firmly establish improved general conditions for attracting investment and build a better image. The Paper identified eight essential conditions for attracting investment: political stability, good governance, macroeconomic reform and stability, trade liberalization, exchange system liberalization, market integration, investment deregulation, and consistency in policy application. Since it would not be feasible to tackle all aspects of investment facilitation at one and the same time, the Paper suggests immediate actions in selected priority areas. They consist of actions to accelerate implementation of the CBI trade reform agenda; investment promotion at the regional and national level; selective legal and judicial reforms; selective tax reforms; and steps to raise awareness and spur the private sector to deliver improvements in services and performance. 40. In implementing the remaining agenda, participation of the private sector through the TWGs will continue to be important. Experience under the CBI suggests that the TWGs have emerged as a crucial part of the CBI process by contributing to ownership and effective implementation of reforms. ANNEX 1 Regional Organizations in Eastern and Southern Africa, A. The Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) 41. The COMESA was established in November 1993, superseding the Preferential Trading Agreement (PTA) for Eastern and Southern African states.20 The aims and objectives of the COMESA Treaty and Protocols are to facilitate the removal of structural and institutional weaknesses of its members through the creation and maintenance of:

42. The fulfilment of the complete COMESA mandate is regarded as a long-term objective. To become more effective as an institution COMESA has defined its priorities over the next 3—5 years as being "The Promotion of Regional Integration Through Trade and Investment." Under the COMESA program, activities in respect of trade liberalization, trade facilitation, payments systems, institutional support, competition policy, investment road maps, strengthening the private sector, and immigration and free movement of persons will be undertaken. 43. The COMESA program includes the establishment of a Free Trade Area (FTA) by the year 2000, to be achieved by the annual reduction of intra-COMESA tariffs. As of end-December 1998, eight countries had achieved a reduction of 80 percent, and six other countries achieved reductions of 60—70 percent. All COMESA countries have reiterated their commitment to achieve a FTA by October 2000, and over half are in a position to make such a transition without having to effect large additional preferences. Member countries have also agreed to adopt a formula on the rules of origin for preferential trade that require the local content to be not less than 35 percent of the ex-factory cost of the goods. COMESA member states have further agreed to establish a customs union with a common external tariff (of 0 percent, 5 percent, 15 percent, and 30 percent) by 2004. In the area of trade facilitation, the COMESA Secretariat is implementing a program to improve the transport and communications systems of the region. These include the adoption of Harmonized Road Transit Charges, a Yellow Card (vehicle insurance) Scheme, Customs Bond Guarantee Scheme, and an Advance Cargo Information System. To provide the required financial infrastructure and service support, COMESA has created specialized institutions in the form of a Trade and Development Bank, a Reinsurance company, and the COMESA Clearing House.21 Institutional support in the form of a Court of Justice, formally created in June 1998, establishes COMESA as an institution with rules which can be enforced through a court of law. The Court will adjudicate and arbitrate on, inter alia, unfair trade practices, interpretation of the treaty, and ensuring that members comply with agreed decisions. In regard to immigration and the free movement of persons, four countries are already in full compliance, while others have committed themselves to fully implementing the protocol. The protocol on the free movement of persons will be implemented in several stages, with the first stage—the removal of visa requirements—to be completed by the year 2000. B. The Southern African Development Community (SADC)22 44. In August 1992, a formal treaty providing for the establishment of SADC was adopted, superseding the Southern African Development Coordination Conference (SADCC).23 This treaty called for the broadening of cooperation among member states in 20 sectors, including transport, health, tourism, mining, and water. 45. The SADC Trade and Development Protocol, signed in August 1996, seeks to establish a SADC Free Trade Area eight years after ratification and the gradual elimination of tariffs and NTBs to trade in the interim. The Protocol has been ratified by only five member states. Others are in agreement on a tariff liberalization program, currently being negotiated by the 11 original signatories of the Trade Protocol. This program is less ambitious than the one agreed by its own member countries under the CBI and under the COMESA. Current proposals call for the removal of all intraregional tariffs within eight years, but do not cover the liberalization of trade with non-SADC countries. Also, unlike agreements under the CBI, proposals regarding trade liberalization among SADC countries allow for special treatment of so-called "sensitive products" (in agriculture, agro-industry, and manufacturing), involving a slower phase-in for import tariff reductions. Moreover, some of the proposals being considered leave open the possibility of excluding some goods/sectors altogether from the trade liberalization exercise. 46. South Africa, on behalf of its partners in the South African Customs Union (SACU),24 has offered to reduce its tariffs at a faster pace than non-SACU SADC countries, although a number of "sensitive" goods—dairy products, wheat, sugar, cotton, fabrics, leather footwear, and vehicles—will be subject to a slower liberalization process. Negotiations within SADC are being held each month under a Trade Negotiating Forum framework. The aim is to reach agreement on a full schedule of tariff reductions before the SADC Summit in August 1999. C. Southern African Customs Union (SACU) 47. The Southern African Customs Union (SACU) was established in 1910 between the newly established Union of South Africa and the separate protectorates of Botswana, Lesotho, and Swaziland. The agreement was renegotiated in 1969 to reflect increases in the partner country shares of regional imports. Namibia became a member of SACU in 1990. The aims of the SACU are to encourage economic development and diversification, in particular in the less-advanced member countries, and afford all parties equitable benefits arising from intra-Union and international trade. The Customs Union Commission, comprising representatives of all the contracting parties, is the supreme consultative body of SACU and meets annually. 48. Under the SACU agreement, members apply the customs, excise, sales, antidumping, countervailing and safeguard duties, as well as related laws, set by South Africa, to goods imported to the common customs area from third countries outside the Union. A SACU member may enter separately into, or amend, trade agreements with a country outside the common customs area, provided the terms of such agreements or amendments do not conflict in any way with the provisions of the SACU agreements. Members may not impose duties or quantitative restrictions on goods grown, produced or manufactured in the SACU area and they may not impose any duties on importation, from any other member, of goods which were imported from outside the common customs area. Each member has its own legislation on quantitative restrictions on goods imported from outside the SACU area. Members, other than South Africa, may, following consultations, apply additional duties or increase duties for protection of infant industries. Rebates, refunds, and drawbacks granted by member countries must be identical, except in specified circumstances. Exceptional trade restrictions by a member may also be justified. There are marketing arrangements under which agricultural imports from other SACU countries may be restricted. 49. All customs, excise, sales and additional duties collected by SACU members are pooled and distributed to members. The shares of BLNS countries are determined on the basis of a revenue-sharing formula and the residual is allocated to South Africa. The original 1910 revenue sharing formula was based on the respective contribution of the BLNS countries to total imports into, and consumption of excisable goods produced within, the SACU area. The 1969 formula provided for an enhancement factor of 42 percent of the shares of the BLNS countries; this factor was introduced to compensate the BLNS countries for negative effects resulting from their participation in SACU. These effects were: (i) the price-increasing effect of the customs union for the BLNS countries and the implicit protection for South African industry; (ii) the industrial polarization resulting from the tendency of industries to locate within the customs union to choose sites in South Africa; and (iii) the loss of fiscal discretion experienced by the BLNS partners because South Africa retained tariff-setting power for the region. Nontariff barriers applied by South Africa also had a negative effect on the size of the revenue pool. Subsequently, the revenue sharing formula was renegotiated in 1975 and a "stabilization factor" was added in 1978, operating retrospectively to 1974/75, to reduce fluctuation in the revenue shares accruing to the BLNS countries. The stabilization factor was centered on a mean of 20 percent of the tax base, with a lower bound of 17 percent and an upper bound of 23 percent. The tax base refers to the sum of duty-inclusive imports, c.i.f., and excise tax-inclusive value of goods produced in the Union and consumed in a particular BLNS country. D. Commission for East African Cooperation (EAC) 50. The EAC between Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania was established in November 1993, and is the most recent in a long line of regional integration arrangements between these three countries.25 Through regional cooperation, the EAC seeks, inter alia, to:

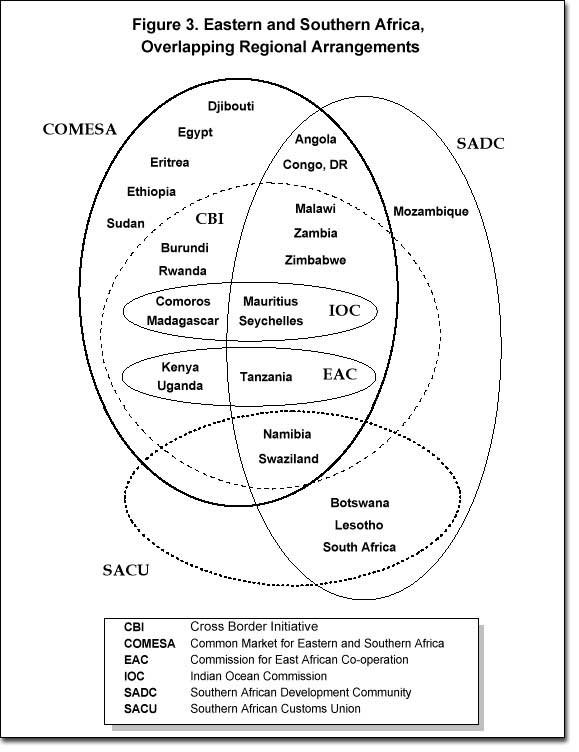

51. The main policy organs of the EAC are: the Summit of the Heads of State, the Permanent Tripartite Commission, the Coordination Commission, and the Secretariat. Since the launching of the EAC, the Tripartite Commission has concentrated on the identification and elimination of physical and policy related constraints, which could slow progress in the establishment of a single market and investment area. Accordingly, much of the work has focussed on formulation of programs to ease the movement of people, goods, services and capital; provide adequate and reliable basic infrastructure; harmonize standards, specifications, trade documentation and investment policies; harmonize macroeconomic and sectoral policies; provide trade financing and other facilities ancillary to the growth of exports; and achieve convertibility of the three East African currencies. 52. As a result of these activities, the EAC has achieved (i) full convertibility of the three East African currencies within the region; (ii) full liberalization of the external current account, and progress towards liberalization of the capital account; (iii) holding of pre- and post-budget consultations in order to harmonize monetary and fiscal policies; (iv) synchronization of the budget day of the three member countries; (v) development of a macroeconomic framework for the region to guide countries towards economic convergence; (vi) launching of the EAC Development Strategy, 1997—2000, which provides for guidelines for economic and social development; (vii) formation of an East African Securities Regulatory Authority to facilitate the establishment of an East African Stock Exchange and cross-listing of stocks; (viii) formation of East African Business Council, comprising private sector organizations to promote cross-border trade and investments; and (ix) the execution of tripartite agreements for the avoidance of double taxation, road transport, and inland waterways. In addition, efforts are underway to eliminate internal tariffs by July 1, 2000, for the launching of an East African passport, and the identification of a EAC designated transport network. E. The Indian Ocean Commission (IOC) 53. The IOC was established in December 1982 by Madagascar, Mauritius, and Seychelles, with the objective of promoting cooperation in trade, agriculture, fishing and ecosystem conservation, as well as cooperation in the cultural, scientific, technical and educational areas. While the IOC has developed a wide variety of regional programs, cooperation in the economic sector has been a priority, as reflected in the implementation of an Integrated Regional Program for Development of Trade (PRIDE)27. 54. The overall objective of PRIDE is to strengthen regional trade integration, specifically by lifting the technical and financial constraints on the private sector of its members. PRIDE is expected to increase business competitiveness, enhance the quality of traded goods, and improve the availability and reliability of trade data. PRIDE has two main components: a macroeconomic component consisting of a general framework of actions to liberalize trade in goods and services, investment, capital movements, and the movement of people;28 and a microeconomic component aimed at facilitating business contacts and partnerships such as participating in trade exhibitions and organizing trade missions. 55. As the IOC member states are also members of COMESA, they subscribe to the trade integration strategy of COMESA. The IOC has also been actively involved in all the preparatory meetings of the CBI, and expects to be involved in its implementation, particularly in those areas that fall within its purview. Bibliography ——, 1996, "The Cross-Border Initiative in Eastern and Southern Africa" SM/96/94 (Washington: International Monetary Fund). ——, 1997, "Trade Liberalization in Fund-Supported Programs" EBS/97/113 (Washington: International Monetary Fund). ——, 1998, "Revenue Implications of Trade Liberalization" SM/98/254 (Washington: International Monetary Fund). Mehran, Hassanali, and others, 1998, Financial Sector Development in Sub-Saharan African Countries, IMF Occasional Paper No. 169 (Washington: International Monetary Fund). 1 - Detailed background information (including on the principles underlying the CBI) was provided in "The Cross-Border Initiative in Eastern and Southern Africa" (SM/96/94, March 14, 1996), and "Initiative for Promoting Cross-Border Trade, Investment, and Payments in Eastern and Southern Africa" (SM/94/91, April 8, 1994). 2 - Comprising Burundi, Comoros, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Namibia, Rwanda, Seychelles, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Recently, Mozambique has expressed its intention of joining the CBI. 3 - See SM/94/91 (Annex). 4 - The Meeting also requested the co-sponsors to prepare a Road Map for Investment Facilitation to be discussed at the Fourth Ministerial Meeting to be held in October 1999. 5 - The TWGs are to act as advisory committees and complement the policy work of the PICs. 6 - LCBIPs had to be completed before end-1995. However, LCBIPs have been agreed for all member countries, except for Burundi and Rwanda. 7 - The remaining two countries—Burundi and Zambia—have expressed the intention of accepting the obligations under Article VIII in the near future. 8 - Although Namibia and Swaziland, as members of the Common Monetary Area (CMA), peg their respective currencies to the South African Rand, an interbank market exists for the determination of forward rates. Comoros has a fixed exchange rate vis-à-vis the French franc, and since January 1, 1999, the Euro. Burundi's franc, and Seychelles' rupee are pegged to baskets of currencies of their main trading partners. 9 - In contrast to a common external tariff structure, the harmonization of external tariffs implies some flexibility for countries to establish their own tariff schedule, while agreeing with its regional partners on parameters such as the number of tariff bands and maximum and average tariffs. 10 - However, Kenya has "stand-by" tariffs on certain imports on top of regular tariffs. 11 - Since these measures were intended to facilitate land-based transportation, Madagascar, Mauritius, and Seychelles were not required to enact them. As for the SACU countries, the timing for the implementation of these measures depended on discussions with South Africa. 12 - This index combines measurements of the restrictiveness of tariffs and nontariff barriers, with a rating of "1" denoting the most open trade regime, and a rating of "10" the most restrictive. For purposes of analysis, countries with a rating of 7—10 were considered "restrictive"; rating of 5—6 "moderate"; and rating of 1—4 "open." For a more detailed description of the index, see "Trade Liberalization in Fund-Supported Programs," Annex I, EBS/97/113. 13 - The select group included non-CBI African countries which had medium-term adjustment programs supported by the Fund in the early to mid-1990s. Comprehensive estimates of the restrictiveness rating for non-CBI African countries in 1993 are not available. 14 - Five CBI countries have trade regimes that are as or less restrictive than that of the average industrial country. 15 - For a detailed analysis see "Revenue Implications of Trade Liberalization," SM/98/254 (November 17, 1998). 16 - See also "Financial Sector Development in Sub-Saharan African Countries," Occasional Paper 169 (1998), Appendix. 17 - Namibia and Swaziland, as members of the CMA, are heavily influenced by interest rate developments in South Africa, although differentials exist between rates in these two countries and South Africa due to differences in reserve and liquidity requirements. 18 - In practice, however, even the central banks with full autonomy face substantial interference from other branches of government. 19 - The need for its ratification has been overtaken by recent economic reforms such as improvements in investment related legislation which generally removed discrimination against foreign direct investment. 20 - At its inception COMESA had 10 members: Ethiopia, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mauritius, Somalia, Swaziland, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Since that time its membership has expanded to 21 members with the addition of Angola, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Madagascar, Rwanda, Sudan, Namibia, Seychelles, and Tanzania, and the withdrawal of Lesotho and Somalia. Mozambique was a member for part of the period. 21 - With the direct availability of foreign exchange to firms and importers, the utilization of the Clearing House has declined. A restructuring of the Clearing House is being considered so that it can improve the management of risk in cross-border payments, including a facility to provide guarantees against political risk. 22 - At its inception SADC had nine members: Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Swaziland, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Since then, five countriesCthe Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mauritius, Seychelles, Namibia, and South Africa have joined the Community. 23 - The SADCC was set up as a rather informal organization by the "frontline" countries with the objective of reducing economic dependence on South Africa. For the most part, the focus of the SADCC activities was on the implementation of projects. 24 - Consisting of South Africa and the BLNS (Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, and Swaziland) countries. 25 - Consisting of the East African High Commission (1948—1961), the East African Common Services Organization (1961—1967), and the East African Community (1967—1977). 26 - To define in clearer terms how cooperation is to proceed, the Heads of State at the last Summit (April 1997), directed that a Treaty to upgrade the current cooperation agreement be prepared, thereby making regional integration more sustainable. It is expected that this Treaty will be signed by July 1999. 27 - Programme Regional Intégré de Développement des Echanges. 28 - Consensus was recently achieved in agreeing on the rules of origin adapted from the COMESA model. |