|

This volume brings together papers that deal with a wide range of macroeconomic

and fiscal issues in oil-producing countries, and aims at providing policy

recommendations drawing on theory and country experience. The scope of the

essays reflects the significant operational involvement of the IMF with oil

producers, particularly in terms of surveillance, program work, and technical

assistance. This work has highlighted the difficult challenges that confront

policymakers in these countries, and the possibilities in several areas for

improved practice.

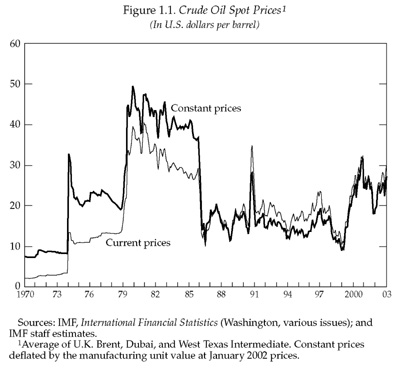

The volatility of oil prices in recent years has brought these major challenges

into sharper focus. Over a period of just a few years, oil prices plunged

to around US$12 per barrel in late 1998, surged to US$30 per barrel in late

2000—only to fall back to US$20 per barrel in early 2002 (Figure 1.1).

This volatility can translate into significant fluctuations in fiscal revenue.

A case in point is Venezuela, where public sector oil revenues fell from

27 percent of GDP in 1996 to less than 13 percent of GDP in 1998 before rising

again to more than 22 percent of GDP in 2000. At the same time, oil is an

exhaustible resource, which poses difficult intergenerational equity questions.

While it may be a distant concern for some producers, for others the reality

of a post-oil period is approaching. And, since oil revenue largely originates

from abroad, its fiscal use can have significant effects on the domestic

economy.

Many oil producers have had difficulties designing and implementing policies

in this context. Studies have shown that resource-dependent economies tend

to grow more slowly than nonresource-dependent ones at comparable levels

of development. Poverty is still widespread in a number of oil-producing

countries. Downturns in oil prices have in a number of cases led to external

and fiscal crises. And a pattern of fluctuating fiscal expenditures associated

with oil volatility has entailed significant economic and social costs for

a number of oil producers.

Oil-producing countries, however, do not form a homogenous group. First,

there is significant variation in the extent of oil dependence. In some countries,

oil accounts for the vast majority of fiscal revenue and exports, while in

others it is less significant for the economy. Second, oil sectors are at

different stages of development. There are several new or soon-to-be producers

where the oil sector is being developed, and oil revenues can be expected

to grow substantially over the next few years. At the other end of the spectrum,

some oil producers like Yemen face the prospect of depleting their oil resources

in the not-too-distant future. Third, governments' financial positions also

vary substantially. Some governments have accumulated sizable financial assets,

while for others public debt is a major concern. This has implications for

the options and constraints in responding to fluctuations in oil prices.

And finally, the ownership of the oil sector also differs across countries.

In countries such as Venezuela and Mexico, the oil sector is dominated by

a state-owned producer. In other countries, the oil industry is largely in

private hands.

Moreover, the way oil revenues are collected and used is not just an economic

issue. Importantly, policies are framed within specific political and institutional

frameworks. These frameworks—including their governance, transparency,

and accountability characteristics—tend to vary among countries. Several

papers in this volume incorporate wider institutional issues specifically

into their analysis.

This book is structured around four broad sets of topics. The papers included

in Part I examine fundamental macroeconomic and fiscal issues and institutional

factors associated with the formulation and implementation of fiscal policy

in oil-producing countries. Part II looks at more specific oil revenue issues,

in particular the taxation and organization of the oil sector, national oil

companies, and oil revenue and fiscal federalism. Institutional arrangements

to deal with oil revenue instability, including oil funds and the use of

oil risk markets, are the focus of the papers in Part III. Finally, the papers

included in Part IV discuss domestic petroleum and energy-pricing issues.

Determining Fiscal Policy in Oil-Producing Countries

Countries with large oil resources can benefit substantially from them,

and the government has an important role to play in how these resources are

used. At the same time, the economic performance of many oil exporters has

been disappointing, even to the extent of prompting some observers to ask

whether oil is a blessing or a curse. The papers in this section address

analytical and operational issues in the formulation of fiscal policy in

oil-producing countries, as well as the political and institutional factors

that may affect the design and execution of policy.

In Chapter 2, Hausmann and Rigobon introduce an innovative analytical approach

to explain the "resource curse." Their model relates the poor growth

performance of many oil-dependent countries to the interaction of government

spending of oil income, specialization in nontradables, and financial market

imperfections. Both the level and volatility of government expenditure contribute

to lack of diversification, which, according to empirical evidence, exacerbates

the resource curse. The main policy conclusions are that welfare and macroeconomic

performance can be improved by reducing the volatility, and in some cases

the level, of government spending; improving budget institutions, debt management,

and policy credibility; and enhancing the efficiency of domestic financial

markets.

Barnett and Ossowski address operational issues in formulating and assessing

fiscal policy in oil-producing countries in Chapter 3. They put forward operational

guidelines based on lessons drawn from the experience of many oil producers.

First, the non-oil fiscal balance should be given greater attention as an

indicator of fiscal policy, and should figure prominently in the budget and

in fiscal analysis. Second, the non-oil balance, and expenditure in particular,

should be adjusted gradually, which requires decoupling, to the extent possible,

government spending from oil revenue volatility. Third, the government should

strive to accumulate substantial financial assets over the period of oil

production, on both sustainability and intergenerational equity grounds.

Fourth, while many oil producers can afford to run sizable non-oil deficits,

there are strong precautionary motives that would justify fiscal prudence.

Fifth, in setting fiscal policy, consideration needs to be given to supporting

the broader macroeconomic objectives. Finally, a number of oil producers

should pursue strategies aimed at breaking procyclical fiscal responses to

volatile oil prices and ensuring that the government's financial position

is strong enough to weather downturns in oil prices.

Eifert, Gelb, and Tallroth (Chapter 4) provide an analysis of the underlying

political and institutional determinants of the economic performance of oil

exporters. Drawing on concepts from the comparative institutionalist tradition

in political science, their paper develops a generalized typology of political

states, which is used to analyze the political economy of fiscal and economic

management in oil-exporting countries with widely differing political systems.

Country experiences point to the key role played by constituencies for the

sound use of oil rents, the importance of transparent political processes

and financial management, and the value of getting the political debate to

span longer time horizons.

Understanding the statistical properties of oil prices is important for

fiscal policy formulation in oil-producing countries. In particular, whether

oil price shocks are deemed to be temporary or persistent has implications

for government wealth (including oil wealth)—a key input for assessing

the sustainability of fiscal policy. In Chapter 5, Barnett and Vivanco test

empirically the statistical properties of oil prices. Accepting that there

are periodic permanent oil shocks (such as in 1973), their evidence suggests

that most oil price movements are transitory. This implies that many year-to-year

oil price fluctuations have only a minor impact on government wealth. For

the most part, therefore—and looking only at sustainability considerations—governments

should not adjust expenditure significantly in response to oil price changes.

Dealing with Oil Revenue

The papers included in Part II of this book address three sets of oil revenue

issues. First, oil extraction plays a crucial fiscal role in generating tax

and other revenue for the government in oil-producing countries. Therefore,

the proper design of the fiscal regime for the oil sector is of key fiscal

importance. Second, there is a need to look at the performance of national

oil companies—including transparency and governance issues—since

in many cases these enterprises play a major macroeconomic and fiscal role.

Finally, three papers are devoted to fiscal federalism topics, as important

questions arise over the assignment of oil revenues to various levels of

government.

Sunley, Baunsgaard, and Simard argue in Chapter 6 that the fiscal regime

must be properly designed to ensure that the state, as resource owner, receives

an appropriate share of oil rent. Competing demands arise between the government

and oil companies over sharing risk and reward from oil investments—where

both aim at maximizing reward while shifting risk as much as possible to

the other party. Abalance also needs to be struck between the desire to maximize

short-term revenue against any deterrent effects this may have on investment

in the oil sector. The paper surveys various fiscal regimes to collect revenue

from the oil sector; cross-country evidence suggests that good fiscal regimes

should guarantee some up-front revenue with sufficient progressivity to provide

the government with an adequate share of economic rent.

In Chapter 7, a paper by McPherson on national oil companies covers an important

area where previous work has been limited. The author argues that the performance

of national oil companies is generally poor, as these enterprises are often

plagued by lack of competition, the assignment of noncommercial objectives,

weak governance, limited transparency and accountability, lack of oversight,

and conflicts of interest. These ills may be addressed by setting performance

standards, increasing competition in the oil sector, divesting noncore assets,

transferring noncommercial activities to the government, and conducting (and

publishing) independent audits on a regular basis. The reform of national

oil companies, however, faces formidable obstacles, including political opposition

and entrenched vested interests. To be successful, reform programs need support

from the highest political levels as well as from a wide range of public

opinion.

The assignment of oil revenues to various levels of government raises a

number of extremely complex issues in oil-producing countries. These include

whether subnational regions should have the right to raise revenues from

natural resources; the ability of subnational governments to cope with oil

revenue volatility given their expenditure assignments; the implications

of various intergovernmental fiscal frameworks for the maintenance of overall

fiscal control by central governments; interjurisdictional equity and redistribution

issues; and environmental and social concerns.

In Chapter 8, McLure provides a conceptual framework for analyzing the assignment

of revenues from the taxation of oil to various levels of government in multilayer

systems. The paper focuses, in particular, on whether subnational governments

should have the power to tax oil, why, and (if so) how. Most of the considerations

examined in the paper suggest that revenues from oil should be reserved for

national governments. There may be overriding legal and political economy

considerations, however, that may lead to the assignment of power to tax

oil to subnational governments.

The next two papers also see the centralization of revenues as the best

solution. Reflecting the complexity of the issues, however, their authors

reach different conclusions regarding second-best policies.

Ahmad and Mottu present a topology of existing oil revenue assignments in

Chapter 9. While recognizing that the centralization of oil revenue is preferable,

they conclude that a second-best solution would be to assign oil taxation

bases with stable elements (such as production excises) to subnational governments,

supplemented by stable transfers from the central government. This would

allow subnational governments to finance a stable level of public services.

The least preferred solution would be oil revenue sharing, which complicates

macroeconomic management, does not provide stable financing of local public

services, and may not diffuse separatist tendencies (oil-producing regions

would still be better off by keeping their oil revenues in full).

Brosio also notes that a growing trend toward sharing of oil revenue with

subnational governments bears out the principle that optimal policies (oil

revenue centralization) often have to give way to second-best solutions (Chapter

10). Based on a review of various types of tax assignments and equalization

mechanisms, he concludes that revenue sharing (including an equalization

mechanism to limit regional disparities in revenues) should be preferred

over the assignment of local taxes on oil. The main reasons are that oil

is typically concentrated in a few regions; oil revenue is highly volatile

and thus difficult for subnational governments to manage; oil taxes are complex

and difficult to administer; and energy policy is a national responsibility.

Institutional Arrangements for Dealing with Oil Revenue Instability

Fiscal policymakers in oil-producing countries need to decide how expenditure

can be insulated from oil revenue shocks, and the extent to which resources

should be saved for future generations. The papers in this section discuss

two institutional mechanisms that have been proposed to promote better fiscal

management. First, oil funds have been suggested as an institutional response

to stabilization and savings concerns, particularly when there are strong

political pressures to increase spending. This is a topic where judgments

on political economy issues can lead to different views, as reflected in

the papers included in this section. Second, a potential way to deal with

the oil price risks that affect the public finances of oil producers is to

use oil risk markets.

Davis, Ossowski, Daniel, and Barnett look at the effectiveness of oil funds

from both a theoretical and an empirical perspective (Chapter 11). The main

types of funds include stabilization funds, savings funds, and financing

("Norwegian") funds. The objective of stabilization funds is to

minimize the transmission of oil price volatility to fiscal policy by smoothing

budgetary oil revenue. Savings funds aim at addressing intergenerational

concerns. Oil funds other than financing funds, however, ignore the fungibility

of resources, and therefore do not effectively constrain expenditure. Moreover,

these funds often do little to improve the conduct of fiscal policy and entail

certain risks, including fragmenting fiscal policy and asset management,

creating a dual budget, and reducing transparency and accountability. Econometric

evidence and country experiences generally raise questions as to the effectiveness

of oil funds.

In Chapter 12, Skancke describes the Norwegian Petroleum Fund. The fund,

which is viewed as a tool to enhance transparency in the use of oil wealth,

is fully integrated into the budget and has flexible operating rules, thereby

avoiding the problems discussed in the previous paper. Since the budget targets

a non-oil deficit that is financed from the fund, the accumulation of resources

in the fund corresponds to net financial public savings. A large-scale buildup

of public financial resources, however, requires a high degree of consensus,

transparency, and accountability—traditionally present in Norway—and

therefore the Norwegian model may not be easily "exported" to many

other oil-producing countries.

Wakeman-Linn, Mathieu, and van Selm note in Chapter 13 that despite the

ambiguous track record of oil funds in other countries, Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan

have created funds to assist them in managing their new petroleum wealth.

The decision to establish funds in these countries was motivated by the serious

challenge posed by an unfinished transition from planned to market economy

in the context of an oil boom, which in the view of the authorities argued

for the separation of oil revenues from other revenues. Given the recent

history of these countries' oil funds, only preliminary conclusions can be

drawn on how they have performed relative to their stated objectives. According

to the authors, on balance these funds, if operated in accordance with existing

rules, should contribute to better management of oil wealth and improved

transparency. However, a further strengthening of these funds is urgently

needed for their potential to be fully realized.

Hedging represents a possible way to reduce oil revenue volatility and limit

oil price risk, as Daniel argues in Chapter 14. Hedging may allow for more

realistic and certain budgeting, provide insurance against declines in oil

prices, and lessen the chances of oil price falls forcing costly fiscal adjustments.

As oil risk markets have matured in the last decade, their range and depth

could allow many oil producers to hedge oil price risk. At the same time,

concerns about the potential political costs of hedging (particularly the

failure to benefit from upturns in prices), institutional capacity constraints,

financial costs, and the depth of the market have discouraged many governments

from actively using hedging. In many cases these concerns could be overcome,

however, and the author encourages governments to explore the scope for hedging

oil price risk.

Designing Policies for Domestic Petroleum Pricing

In oil-producing as well as oil-importing countries, domestic petroleum

product prices are often heavily regulated. Many governments keep prices

below international levels, resulting in the implicit or explicit subsidization

of oil consumption. The quasi-fiscal costs and appropriateness of setting

domestic prices at below-market rates, as well as the potential social consequences

of price reform, are contentious and deeply political issues in many countries.

Gupta, Clements, Fletcher, and Inchauste (Chapter 15) argue that the subsidization

of petroleum products in oil-producing countries does not appear to be a

wise use of resources. Petroleum subsidies are inefficient and inequitable,

implying substantial opportunity costs in terms of foregone revenue or productive

expenditure, and procyclical, thus complicating macroeconomic management.

Moreover, as these subsidies are typically not recorded in government budgets

as expenditures, their economic cost, as well as the incidence on different

income classes, is often poorly understood. Despite the substantial costs

of implicit petroleum subsidies, reform is often difficult, as there is typically

strong popular opposition to their elimination. Support for subsidy reform

can be promoted through countervailing measures and publicity campaigns.

Undertaking poverty and social impact analyses and establishing social safety

nets can mitigate the adverse social and political effects of reforming energy

subsidies.

In Chapter 16, Espinasa provides a simple accounting model to analyze the

distribution of the cost of domestic petroleum subsidies between the government

and the national oil company. It is found that the fiscal incidence of this

cost depends on the fiscal regime in place. Some tax regimes shift the burden

of subsidies to the state oil company, thus hampering its ability to invest

and hence to provide the government with revenues over the medium term. In

addition, estimates of the implicit subsidies should take into account domestic

distribution and retail costs, which typically represent a sizable share

of the final retail price.

In Chapter 17, Federico, Daniel, and Bingham examine the case for smoothing

retail petroleum prices in countries where these prices are regulated by

the government. The authors contend that full and automatic pass-through

of international price changes to domestic retail prices is the first-best

solution in a competitive market economy, as it allows for correct price

signals and does not expose the government to undue fiscal risk as a result

of volatile oil prices. However, most developing countries that regulate

petroleum prices follow a discretionary approach to adjusting them, which

suggests that from a political economy perspective full-cost pass-through

is not a robust policy option. The paper therefore explores the case for

government-managed retail price smoothing. It concludes that there is a sharp

trade-off between the degree of price smoothing and government fiscal stability.

Since many pricing rules would leave the government overexposed to oil price

risk, only limited price smoothing is likely to be fiscally sustainable.

Energy sector operations often lead to quasi-fiscal activities. Petri, Taube,

and Tsyvinski stress in Chapter 18 that this is the case in many of the countries

of the former Soviet Union. Their study provides an analysis of quasi-fiscal activities arising from the mispricing of energy and the toleration of payment arrears. In addition to information on various countries of the former Soviet Union, the paper presents detailed case studies on Ukraine (a net energy importer) and Azerbaijan (an energy-rich country). The main policy recommendations in the paper focus on the need to adjust inappropriately low energy tariffs and improve financial discipline in order to reduce energy consumption and waste and streamline untargeted energy subsidies; to supplement these reforms with the provision of explicit and better targeted subsidies to needy population groups; to include estimates of quasi-fiscal activities in the reported fiscal positions; and to enhance the scrutiny of these activities and promote fiscal transparency.

|