Prospects for Oil Market Stability, Remarks by John Lipsky, First Deputy Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund, at the G-8 Meeting of Energy Ministers, Rome

May 22, 2009

At the G-8 Meeting of Energy Ministers

Rome, May 25, 2009

As prepared for delivery

| Download the presentation (262 kb PDF) |

It is an honor to have the opportunity to address this important meeting of the G-8 Energy Ministers. As you know, energy policy is not a direct part of the IMF’s mandate of promoting economic and financial stability, but there are important linkages between energy markets and the global economy. As recent developments have demonstrated clearly, oil market stability is important for global economic stability, and vice versa. In my remarks, I will discuss prospects for a return to global oil market stability after a period of dramatic oil price volatility, building on a review of the causes of the recent large oil price fluctuations and the lessons from the recent oil price boom and bust.

The Global Recession and Oil Market Adjustment

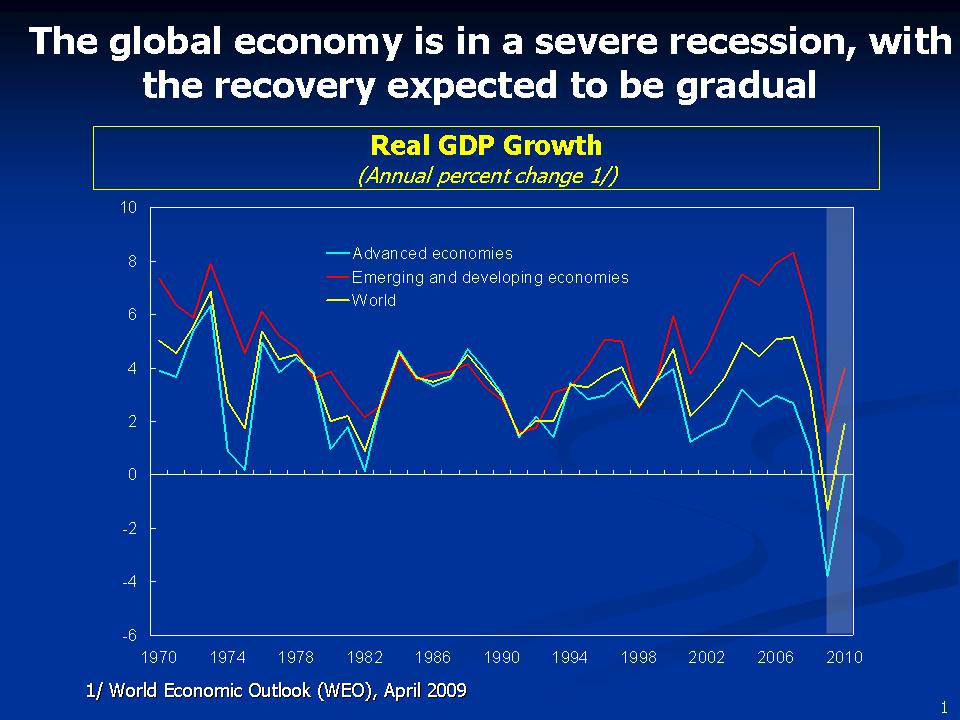

The dramatic deterioration in global economic conditions late last year brought an abrupt end to the combination of robust demand growth and capacity constraints that had shaped oil market developments over the past few years. Over the course of just a few months, the global economy dropped into the most severe recession of the post-World War II period.

The medium-term outlook weakened as well, as the financial crisis will have lasting effects on credit and capital flows. In particular, economic growth in emerging and developing economies is unlikely to return quickly to the very high rates registered in 2003-07.

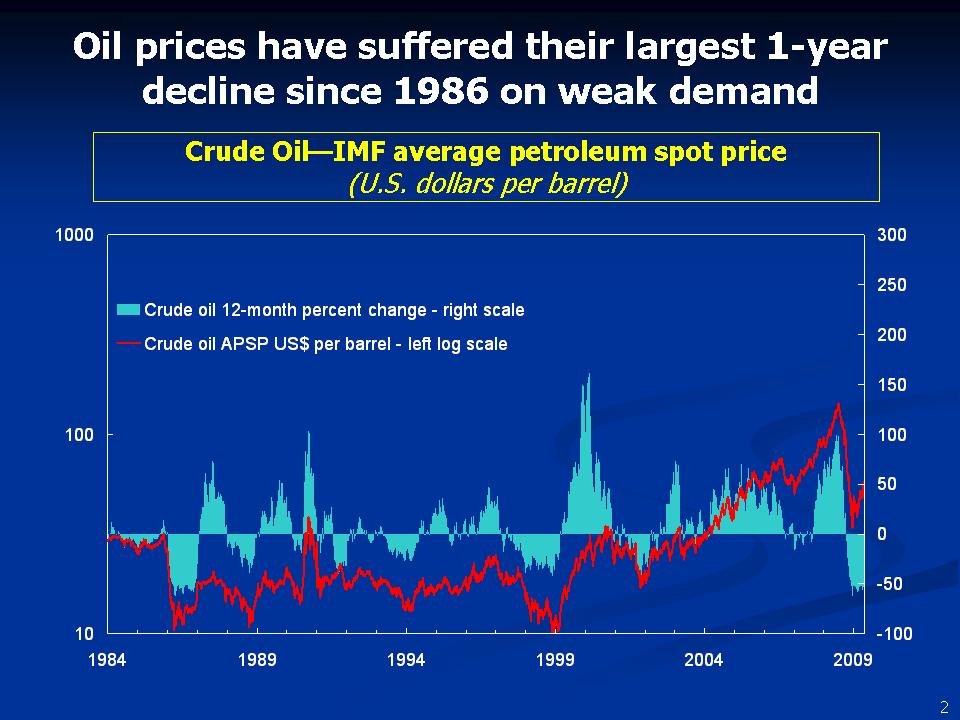

The oil price response to the rapid deterioration in global economic growth prospects was dramatic. By the end of last year, crude oil prices had fallen by more than 70 percent from their earlier peaks. This represented the largest percentage drop ever experienced over such a short period, surpassing even the declines of 1986. But the severity of the recession and the speed at which global economic conditions have changed also are without modern precedent.

Momentum trading became a pointed concern during the financial turmoil of September-October last year. Like others, commodity investors became increasingly wary of counterparty risks and were faced with reduced credit access. The resulting unwinding of positions reduced liquidity in oil futures and increased price volatility. While this unwinding may have contributed to the accelerated price declines at the time, the momentum did not last. Commodity financial markets broadly stabilized as early as last December.

In early 2009, oil prices, stabilized. In recent weeks, they have risen to almost $60 a barrel, reflecting a general improvement in sentiment on signs that the sharpest period of decline in the global economy is over, that growth in China may be picking up, but also on expectations that the contraction in oil demand may bottom out soon.

The Lessons from the Recent Oil Price Boom and Bust for Oil Market Stability

Turning to the lessons of recent experience, the extraordinary rise and fall in oil prices over the past few years once again has illustrated how oil markets can be susceptible to high price volatility and instability. There are several reasons for this vulnerability.

First, oil prices have a tendency to respond very strongly to short term shifts in the global economic outlook. Thus, changes in underlying economic fundamentals can lead to larger oil price changes in the short term than in the medium term. The main reason for this pattern in price adjustment is the low short-term responsiveness of oil demand and supply to changing global market prices. Even small demand shifts can result in large initial shifts in spot prices in order for markets to clear. Typically, such shifts subsequently unwind gradually as demand and supply eventually respond to the change in prices.

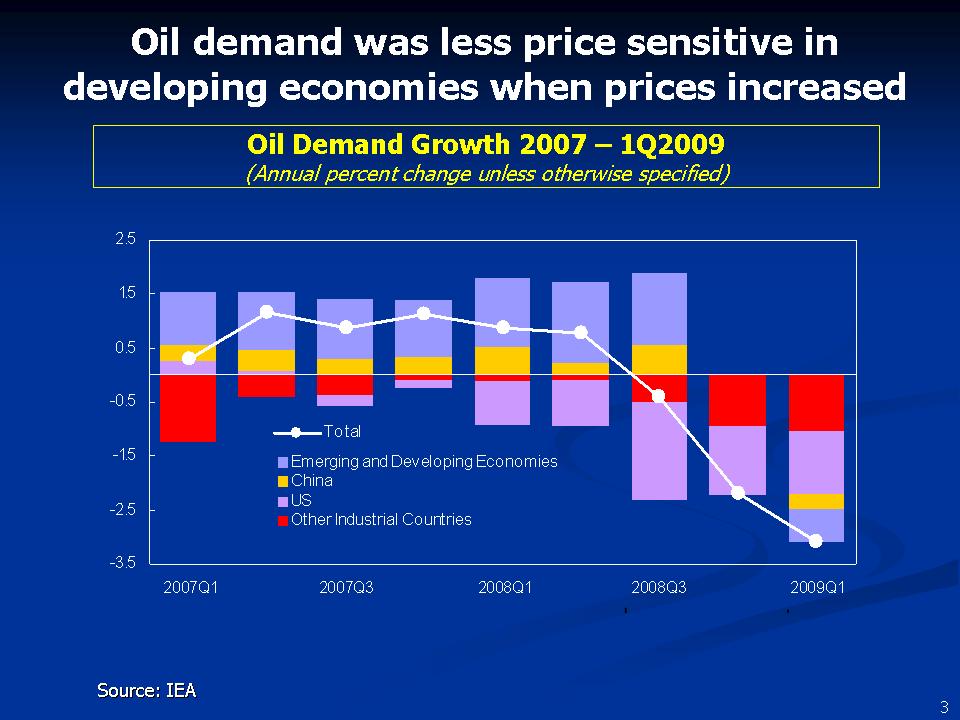

An important feature of the recent boom was an apparent further reduction in the already low sensitivity of global demand to higher global market prices. This decrease can be traced partly to government action seeking to smooth the impact of the upswing in international prices on local retail prices, particularly in many emerging and developing countries.

In contrast, demand in the advanced economies was more responsive to rising prices, as the pass-through of international market prices to domestic end-user prices typically is more rapid and complete. Similarly, lower world market prices in the downturn often have not been passed on to domestic prices.

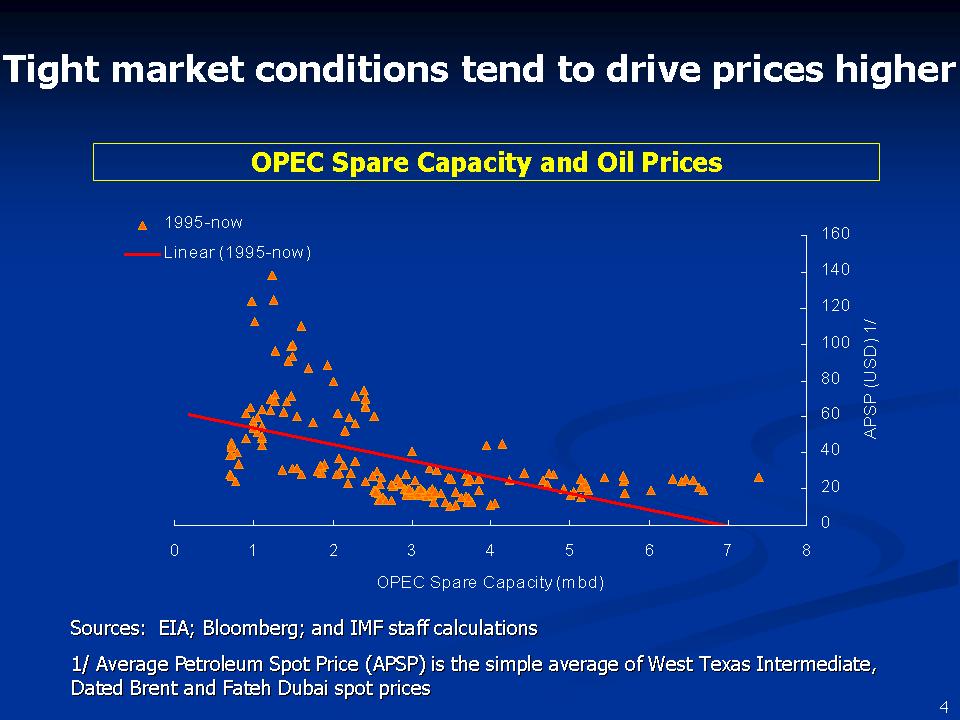

Another time-honored lesson is that when market conditions are tight and buffers are low, prices respond very strongly to signals of scarcity. Temporary supply disturbances are a well-known phenomenon in commodity markets, and for this reason, price spikes occur relatively frequently. Oil markets are no exception. One of the characteristics of the most recent boom, however, was that scarcity was not just the result of the usual short-term factors, such as weather- and conflict-related outages, but also of persistent supply constraints. While there was a strong demand impetus from buoyant global growth, oil production broadly stagnated during 2006-08. Fundamentally, the oil market had entered a new regime, as spare capacity dwindled after two decades of substantial excess capacity in the system.

The stagnation in global oil production reflected a confluence of factors. Some of them were obviously short-term in nature. Most importantly, however, the stagnation highlighted unexpectedly large difficulties in bringing new capacity on stream. We have discussed the main reasons extensively in past World Economic Outlook publications, so I will be brief.

• Cyclical factors. With the global economy booming, and given the legacy of downsizing in the 1990s, capacity limits in the oil services and oil equipment industries led to sharply higher investment costs and project delays. This represents one reason why time-to-build lags have increased.

• Geological and technical factors. New oil fields typically are smaller in size and involve greater technological and geological challenges than in the past, while the decline rates of existing fields in some regions are proving to be faster than expected. Development and exploration costs per barrel in new fields are thus higher in constant dollars than they were when older fields were developed, while time-to-build lags have increased.

• Policy factors. The investment climate deteriorated in a number of countries during the boom, deterring investment., These factors include reserve access terms, and policy parameters affecting investment returns, such as tax policy environment,

During the price run-up in 2007-08, a growing consensus emerged that these supply problems would be more severe and longer lasting than had been expected previously, particularly against a backdrop of continued robust global growth. The key consequence of this prospective scarcity was that prices continued rising. Another consequence was that price expectations lost their anchor, a difficulty exacerbated by data limitations that complicate the assessment of oil market conditions.

Another conclusion that we have drawn from the oil price boom and bust is that, despite often repeated claims to the contrary, there is no concrete evidence of a sustained price impact of commodity financial investment. For example, research by IMF staff and others have not detected any systematic connection between various measures of such investment and either price volatility or price changes in recent years. An important insight from the debate on the price impact of commodity financial investment is that if oil price increases were systematically driven by ill-informed financial investors and not by fundamentals, oil inventories would increase in order for spot oil markets to clear. But this was not the case during the price boom of 2007-08. This is not to say that financial investors do not have any short-term price impact. In particular, IMF analysis indicates that portfolio shifts into commodity assets in late 2007 and early 2008 represented a temporary contributing factor to the rapid rise in oil prices at the time.

Prospects for Oil Market Stability

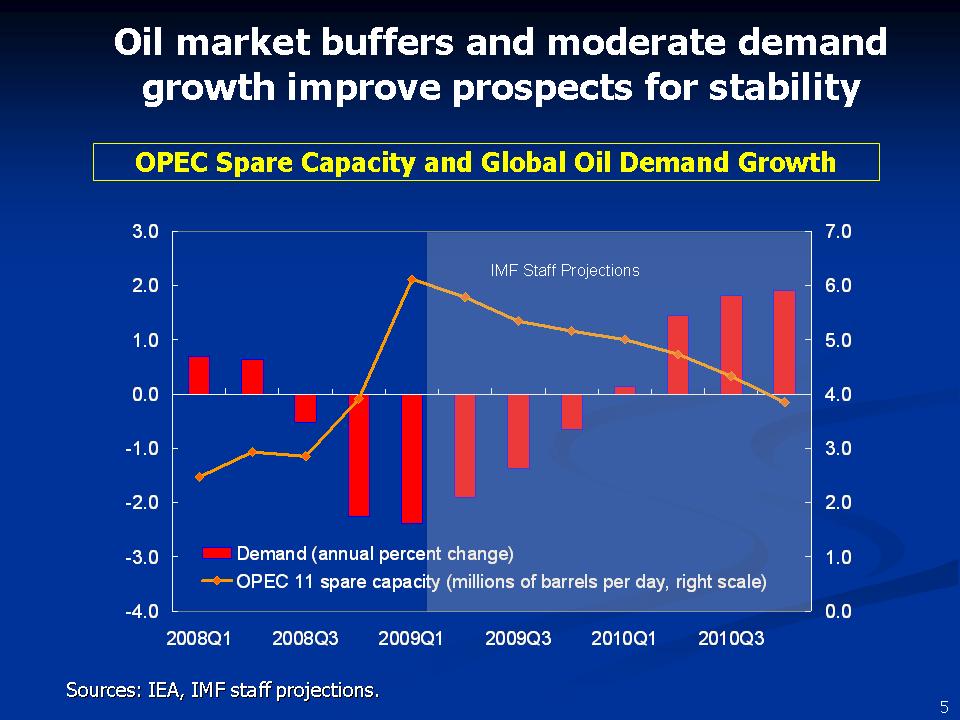

More recently, oil price volatility has decreased from the high levels seen last year, and further near-term declines are likely, for two reasons. First, global oil demand is expected to recover only gradually, reflecting the prospect of a gradual global growth recovery.

Second, buffers are higher than they were during the boom. Spare capacity in OPEC producers has risen substantially. The IEA estimates that OPEC-11 spare capacity in April was 6.3 million barrels a day, more than twice the recent average of some 3 million barrels. Inventories also are much higher than usual in the OECD economies. The inventory forward demand cover is estimated to have reached more than 62 days by end-March, substantially above the recent 5-year average of some 53 days. With buffers at such comfortable levels, upside price risks from factors such as short-term supply shortages should remain limited for some time.

Of course, producer policies also will play a role in determining the market outlook. In particular, if the expected recovery in demand is not accommodated by increased capacity utilization, the price rebound is likely to be stronger than reflected in current consensus views. Price volatility would then remain relatively higher, especially if there is uncertainty about producers’ objectives or supply responses.

Turning to the medium term, buffers are unlikely to remain at their current comfortable levels. On the demand side, oil consumption eventually will return to a path of more robust growth, as economic growth recovers in emerging and developing economies, accompanied by advancing industrialization and rising vehicle ownership. Depending on capacity growth, oil supply constraints could again become binding, driving price increases.

In this respect, a widely voiced concern is that the combination of financial crisis, low current oil prices, and much higher oil price volatility may represent a setback to capacity expansion. Press reports and indicators such as rig counts suggest that oil investment in 2009 will have declined. For example, the March international Baker-Hughes rig count was almost 10 percent below its September 2008 peak. These declines should not come as a surprise. Lower oil and product prices have reduced both profitability and the availability of internal financing, while external financing conditions have become more challenging. With a slow rebound in global growth and continued financial strain in prospect, investment in 2010 is likely to remain subdued as well.

It is too early to assess the extent of the actual set back for oil sector capacity expansion. In fact, there are some reasons for optimism: Large international and national oil companies will continue to invest, despite some reduction in total capital expenditure. These companies had initiated significant expansion projects while oil prices were rising. The sunk costs of the many large projects already in train are simply too large for the projects to be closed down. Moreover, investors are likely to look beyond current oil market weakness. Another helpful factor is that the broad-based decline in global capital spending and lower metals prices should reduce the costs of new oil investment, partly offsetting the adverse effects of lower oil prices on investment incentives.

But there also are reasons for concern. First, a good part of gross investment spending simply sustains current production capacity, reflecting the current, relatively rapid field decline rates in many parts of the world. Second, the many policy constraints on oil investment mentioned earlier remain in place. The persistence of current obstacles could again trigger doubts that the need for increased capacity will be met, which, in turn, could then lead to a renewed sense of aggravated scarcity.

In sum, while “scarcity” is not an imminent problem, oil supply constraints remain a medium-term worry. With long time-to-build lags, significant setbacks to oil investment today could set the stage for future sharp price increases.

Policies to Foster Oil Market Stability

There is clear evidence that large, rapid oil price changes are detrimental to both global growth and to global economic and financial stability.

It is therefore policymakers’ responsibility to look for effective ways to reduce oil price volatility and limit the scale and frequency of large price swings, as well as to cushion their economic impact. While perhaps attractive in theory, limiting price fluctuations through direct intervention is unlikely to be either effective or feasible in practice, especially over longer horizons, and may very well be counterproductive. Fundamentally, policies should instead address the principal factors underlying large oil price swings.

Our policy recommendations remain broadly unchanged from earlier expositions. As the background paper discusses them in some detail, I will mention only some key elements. On the demand side, policy efforts should focus on strengthening the responsiveness of domestic end-user prices to changes in market conditions. Oil demand would become more responsive to price signals, even in the short term, reducing the tendency for large price movements. On the supply side, policy efforts aimed at achieving more stable and predictable investment and tax regimes will encourage adequate investment. Finally, more timely, complete, and accurate data on oil demand, supply, and inventories are critical to reducing oil price volatility, given current difficulties in assessing oil market conditions.

Conclusions

In summary, the recent extraordinary fall in oil prices reflects mainly a natural response to an abrupt, dramatic change in global economic growth prospects. Near-term factors point to relative oil market stability, as spare capacity and inventories are at comfortable levels, while the near-term rebound in demand is expected to be modest. Nevertheless, supply constraints eventually could reemerge, threatening medium-term oil market stability. To avoid excessive price swings, efforts by producers, consumers, financial investors, and market regulators alike will be needed to improve the transparency, functioning, oversight and, ultimately the supply-demand balance, in global oil markets.

IMF EXTERNAL RELATIONS DEPARTMENT

| Public Affairs | Media Relations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-mail: | publicaffairs@imf.org | E-mail: | media@imf.org | |

| Fax: | 202-623-6220 | Phone: | 202-623-7100 | |