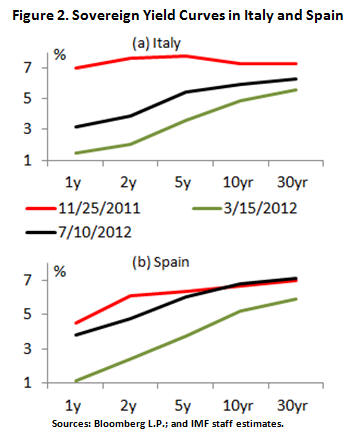

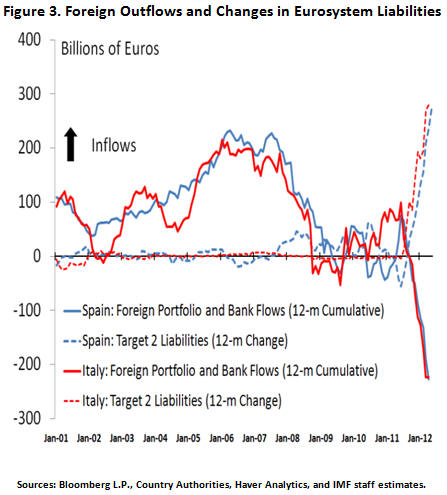

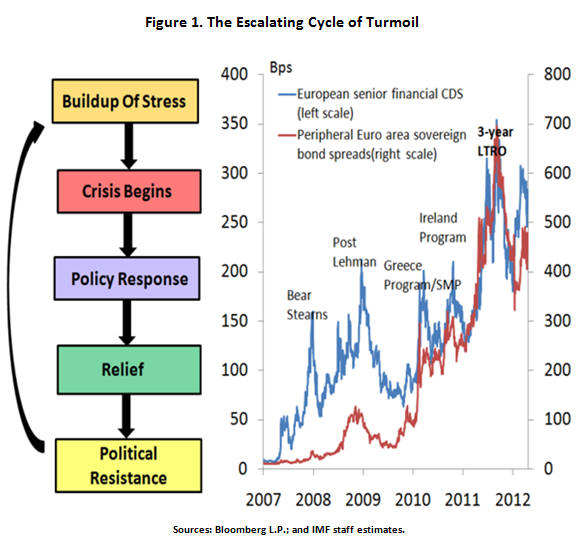

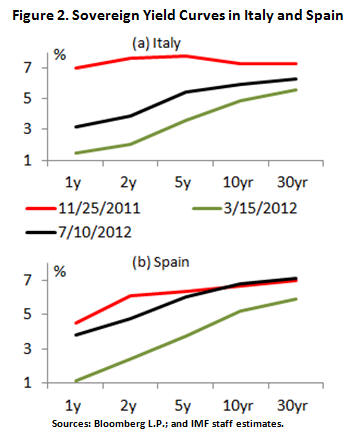

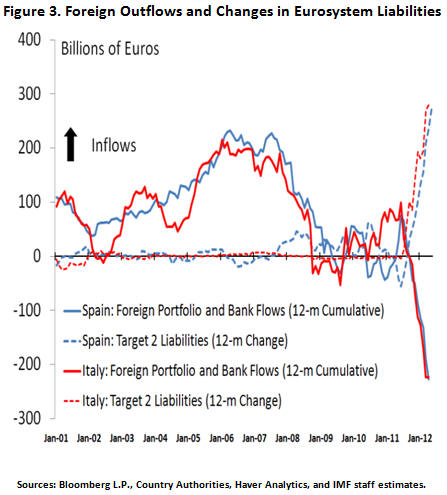

Yields on sovereign debt in the periphery rose sharply as renewed concerns about economic growth and the health of banks curtailed market access [Figure 2(Data)]. The 3-year LTROs helped support demand for peripheral sovereign debt but that positive effect has waned. Private capital outflows continued to erode the foreign investor base in Italy and Spain [Figure 3(Data)].

A flight to safe assets led to a collapse of yields on government bonds in the U.S., Germany, and Switzerland, and pushed the dollar to a 20 month high against major currencies. Safe-haven inflows drove Japanese government bond yields to near historical lows and yen appreciation has created headwinds for the economic recovery. Within the EU, Sweden and Denmark have also served as additional safe havens. Growing risk aversion contributed to weakened confidence in emerging markets (EM), amid increased concerns about their ability to tackle homegrown vulnerabilities, especially given their diminished policy room and a weaker global outlook.

At the end of June, European leaders agreed upon significant positive steps to address the immediate crisis. The agreement, if implemented in full, will help break the adverse links between sovereigns and banks and create a banking union. In particular, once a single supervisory mechanism for euro area banks is established—with key decisions to be taken by end-2012—the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) could have the possibility to recapitalize banks directly. Moreover, ESM assistance will not carry seniority status for Spain. After a short-lived rally, Spanish and Italian bond yields have deteriorated again amid volatile trading conditions, as market participants focus on implementation risks and the need for broader steps toward pan-European risk sharing.

Strains in EU funding markets have intensified and deleveraging pressures remain elevated.

Notwithstanding the ample liquidity provided by the ECB’s refinancing operations, funding conditions for many peripheral banks and firms have deteriorated. Interbank conditions remain strained, with very limited activity in unsecured term markets, and liquidity hoarding by core euro area banks. Bank bond issuance has dropped off precipitously, with little investor demand even at higher interest rates. Banks in the euro area periphery have had to turn to the ECB to replace lost funding support, as cross-border wholesale funding dried up, and deposit outflows continue.

The April 2012 GFSR noted that EU banks are under pressure to cut back assets, due to funding strains and market pressures, as well as to longer-term structural and regulatory drivers. The sharp reduction in bank balance sheets in the fourth quarter of 2011 continued, albeit at a slower pace, in the first quarter of 2012. Growth in euro area private sector credit diverged significantly. While credit has contracted in Greece, Spain, Portugal and Ireland, it has remained more stable in some core countries. Survey data on bank lending conditions show that credit supply remains tight, albeit less so than at the end of 2011, but that demand has also weakened more recently. Deleveraging is also a concern for many peripheral corporations, given their historic dependence on bank funding and the risk that credit downgrades and diminished investor appetite could drive borrowing costs higher, even for high credit quality issuers.

Bank downgrades have raised the prospect of higher funding costs for many banks. Moody’s credit rating agency recently downgraded 15 European and U.S. banks with large capital markets operations. The downgrades reflected concerns about diminished longer-term profitability of these firms due to risks inherent in their capital markets activities, challenging funding conditions, and tighter regulatory requirements. The rating actions also reflected the size and stability of earnings from non-capital market activities, liquidity buffers, risks from exposures to Europe, U.S. residential mortgages, commercial real estate or legacy portfolios, as well as any record of risk management problems. S&P took similar actions in November 2011.

Measures to stabilize the Spanish banking system have not yet restored market confidence.

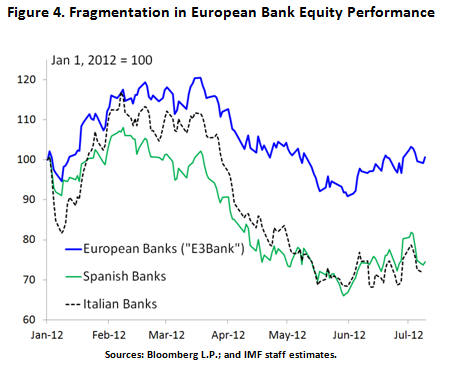

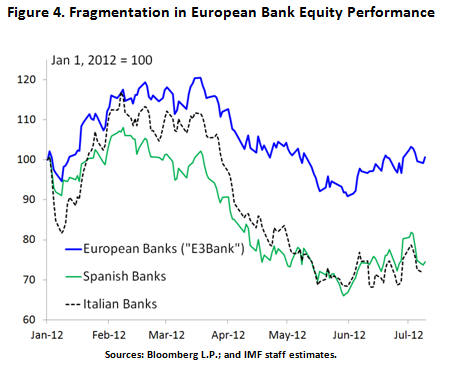

Concerns over the recapitalization needs of the Spanish banking system have resulted in sharp declines in the equity market [Figure 4(Data)]. Wholesale funding costs for Spanish banks also returned to late 2011 highs for both covered bonds and unsecured debt.

Investors took little comfort from Spain’s request for external assistance on June 10 to support its domestic banking system. While the request for external support does provide a welcome backstop for restructuring segments of the banking sector, the initial adverse market response reflected the lack of a comprehensive program to restructure the banking system and lack of details about the loan. Some market participants also expressed concern that the support, in the form of a loan to the sovereign, could represent a claim that is senior to current holders of Spanish government debt. The decision at the end-June summit of EU leaders that financial support could take the form of direct recapitalization of banks and would not enjoy preferred creditor status helped to allay some of these concerns.

A complete set of policies providing a pan-European solution remains a work in progress.

The measures announced at the European leaders’ summit in June are steps in the right direction to address the immediate crisis. Additional steps to cement this progress in the short term include the following:

- Policymakers must resolve the uncertainty about bank asset quality and support the strengthening of banks’ balance sheets. Bank capital or funding structures in many institutions remain weak and insufficient to restore market confidence. In some cases, bank recapitalizations and restructurings need to be pursued, including through direct equity injections from the ESM into weak but viable banks once the single supervisory mechanism is established.

- Countries must also deliver on their previously agreed policy commitments to strengthen public finances and enact sweeping structural reforms.

The recent initiatives are steps in the right direction that will need to be complemented, as envisaged, by more progress toward a full-fledged banking union and deeper fiscal integration. By setting in motion a process toward a unified supervisory framework, the European summit put in place the first building block of a banking union. But other necessary elements, including a pan-European deposit insurance guarantee scheme and bank resolution mechanism with common backstops, need to be added. In the shorter run, timely implementation, including through the ratification of the ESM by all members, will be essential. In addition, these steps would usefully be complemented by plans for fiscal integration, as anticipated in the report of the “Four Presidents” submitted to the summit.

Supportive monetary and liquidity policies remain crucial as well. The recent interest cut by the ECB is welcome, but there is room to further ease monetary policy. The LTROs have helped to bring down the cost of secured and unsecured interbank lending for many European banks, but alone are not sufficient to restore investor confidence or provide a lasting solution. If economic conditions continue to deteriorate, unconventional measures could be used. This means giving consideration to non-standard measures, such as a re-activation of the Securities Markets Program (SMP), additional LTROs with suitable collateral requirements, or the introduction of some form of quantitative easing. New ECB collateral rules have played an important role in easing liquidity constraints, and any new tightening of collateral rules should be avoided.

Risks to global financial stability are also present in the United States.

Outside of Europe, the U.S. fiscal cliff —the convergence of tax cuts expiring and automatic spending cuts kicking in at year-end—has received increased focus in recent weeks. If no policy action is taken, the fiscal cliff could result in a fiscal tightening equivalent to more than 4 percent of GDP (see the accompanying Fiscal Monitor Update).

As year-end approaches and uncertainty increases, another bout of political brinksmanship —similar to that seen in August 2011 in discussions of the U.S. debt ceiling—could trigger increased market volatility. A complicating factor is that the debt ceiling could be hit around the same time as the fiscal cliff. During the last debt ceiling episode, rates on near-term money market instruments increased, repo transaction volumes fell, the Treasury bond curve steepened, and sovereign credit default swap (CDS) spreads inverted. Although the debt ceiling was ultimately raised, S&P lowered its sovereign credit rating on the United States from AAA to AA+. They continue to maintain a negative outlook, citing deterioration in the US fiscal outlook and the lack of political consensus over its resolution. Most markets, however, are not yet pricing in enhanced fiscal risks. U.S. CDS spreads have picked up, but remain at low levels.

The market consensus is that the bulk of fiscal tightening will be deferred until later and that the debt ceiling will be raised in time to avert a default. However, there is clearly the potential for a significant adverse market reaction should market participants reassess the likelihood of a fiscal cliff, given its potentially severe effects on the U.S. economy. The federal debt ceiling should also be raised well ahead of the deadline (most likely falling into early 2013) to mitigate risks of financial market disruptions and a loss in consumer and business confidence. Meanwhile, a lack of progress on a credible consolidation plan risks triggering additional sovereign credit rating downgrades. Further downgrades could increase term premia, leading to a loss in liquidity, and—given the widespread role that Treasuries play in the pricing and collateralization of other assets—have a destabilizing impact on broader markets and global market sentiment.

Emerging markets have not escaped contagion, and are also dealing with home-grown vulnerabilities.

Emerging markets are facing extraordinary uncertainty about external conditions impinging on their economic performance. Earlier this year, policymakers across several EM economies were still worried about large-scale capital inflows and excessive appreciation of their currencies. Such fears have given way to concerns about overly rapid depreciation and increased volatility, as currencies like the Brazilian real or the Indian rupee depreciated by between 15 and 25 percent in less than one quarter.

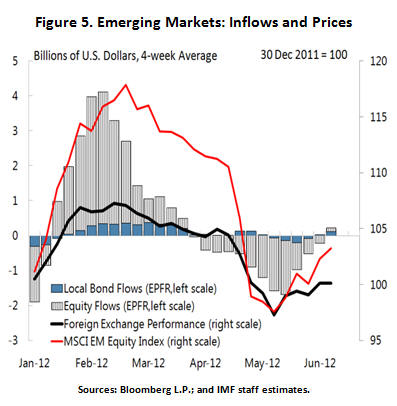

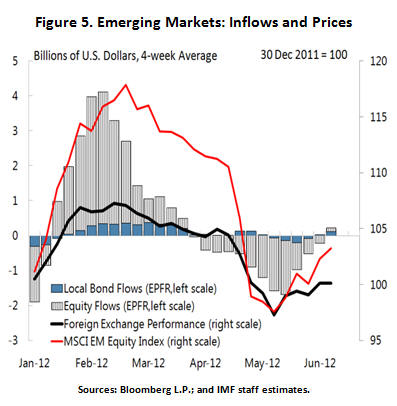

Equity markets in EMs rebounded strongly during the first two months of 2012, but have since reversed much of these gains [Figure 5(Data)]. Compared to equity flows, there have been minimal bond flows out of local markets. Indeed, many foreign bond investors have opted to hedge currency risk selectively rather than withdraw from markets. This dynamic has helped to put a floor on bond prices during periods of heightened global risk aversion. However, if sizable bond outflows were to materialize, bond yields could spike and destabilize domestic markets. In that case, countries may have to rely more on exchange rate flexibility, draw more intensely on foreign exchange reserves or undertake other policy measures to counter disorderly market conditions.

Market participants are also concerned about slowing domestic growth, which could erode bank profitability and pose some risks to financial stability, for instance in Brazil, China, and India. The uncertainty about asset valuations and economic growth has put pressure on bank stocks in recent months. Demand for credit has fallen in a number of countries, even where government-supported credit has been available.

There are noticeable differences across regions.

Central and Eastern Europe are the most exposed to the euro area and could suffer disproportionately from an accelerated withdrawal of bank funding or portfolio capital. Asia appears better shielded from the euro area crisis, reflecting limited direct financial linkages and strong foreign exchange buffers. Nonetheless, conditions in regional dollar funding markets have tightened since mid-March and rising global uncertainty and weaker external demand are causing headwinds for export-dependent economies such as the Republic of Korea. Growth in China has also slowed, weighing on markets across Asia, as well as on global commodity prices. India is a rising concern, with the rupee recently weakening to new record lows, as the need to finance large fiscal and current account deficits is pressuring markets, though financial restrictions have facilitated the financing of the fiscal deficit. In Brazil, the central bank has cut the policy rate to a record low to counteract a sharp deceleration in the real economy. Some of the regulatory measures taken in 2011 to slow capital inflows and the growth in consumer credit have also been reversed.

EM policymakers face challenges as well.

Many EM countries still have room for monetary easing to respond to large adverse domestic or external shocks, while fiscal stimulus remains a second line of defense for a number of countries in case of a major shock to growth (see the Fiscal Monitor Update). Inflation is generally within target ranges, suggesting scope for further cuts in interest rates should large shocks materialize. Many EM countries with policy room to respond to shocks would still benefit from further rebuilding of policy buffers at this stage, given strong commodity prices and still-favorable liquidity conditions. In contrast, a large policy-induced credit stimulus could be less effective, and certainly less desirable, than in 2008/9. Relative to other EMs, large economies such as Brazil, China, and India have benefited from strong credit growth in recent years, and are at the late stages of the credit cycle. Expanding credit significantly at the current juncture would heighten asset quality concerns and potentially undermine GDP growth and financial stability in the years ahead.

For policymakers, the current constellation of conditions poses significant challenges. Persistent fears of sharp downside shocks have kept accommodative policy conditions in place in many EM countries, which over time could generate new imbalances and threats to financial stability. Low interest rates create an incentive to accumulate debt, while boosting asset prices. In a few large emerging economies (India, Russia, Turkey), fiscal space is being rebuilt more slowly than is desirable (see Fiscal Monitor Update). Financial policies may be less conservative than would be appropriate in EMs at an advanced stage of the credit cycle. If and when a large downside shock ultimately materializes, these combined vulnerabilities could quickly come to the fore, putting financial stability to a serious test.

The regulatory reform agenda is now focused on rulemaking and implementation, but progress has been uneven.

The focus of the regulatory reform agenda has shifted from development of standards to rulemaking and implementation. A few G-20 countries (India, Japan, Saudi Arabia) have already announced final rules for implementation of Basel III from early 2013, but the majority are still in the drafting or consulting stage. The EU has moved closer to a final rule with the European Council agreeing on a compromise Capital Requirements Directive IV (CRD IV) package. The U.S. authorities issued a final rule introducing capital standards closely aligned with Basel 2.5 as of January 2013, and published for consultation the rules for incorporating Basel III capital standards into their regulatory framework.

Other elements of the reform agenda are still evolving, and implementation has been patchy. On over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives, all jurisdictions and markets need to aggressively push ahead to achieve full implementation of market changes in as many areas as possible, by the end-2012 deadline set by the G-20 leaders. Specifically, moving all standardized derivatives trading to exchanges or electronic trading platforms, where appropriate, and clearing them through central counter parties (CCPs). With rising concerns that CCPs could become the new global systemically important financial institutions, there is now greater urgency for developing and agreeing on resolution arrangements for them. Progress on developing resolution frameworks more broadly has been slow, with many jurisdictions still lacking the necessary statutory resolution tools. Legal reforms to align national resolution regimes with the Financial Stability Board’s Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes are under way in many jurisdictions. The European Commission’s recent draft directive establishing a framework for the recovery and resolution of credit institutions and investment firms is an important step forward. That said, the euro area still needs to make further progress toward establishing an integrated supervision, crisis management and resolution framework.