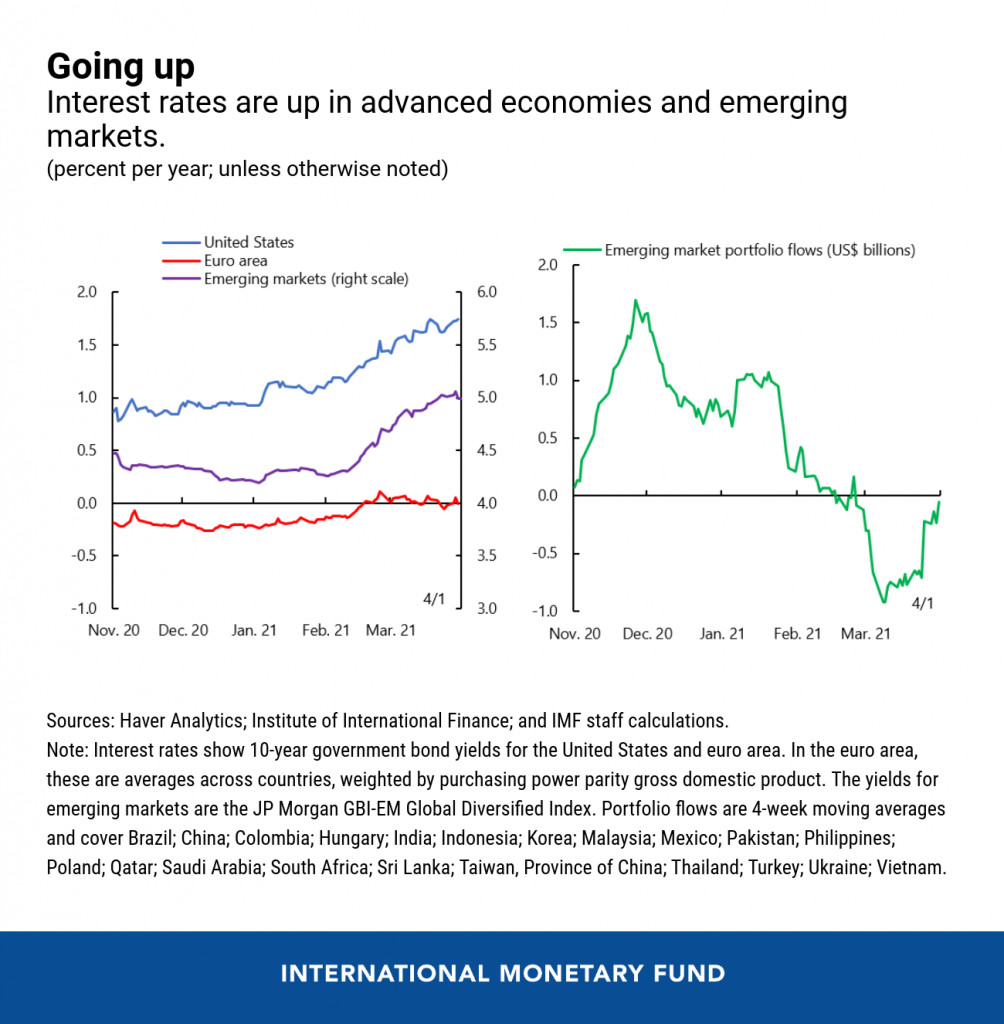

Rapid vaccine rollout in the United States and passage of its $1.9 trillion fiscal stimulus package have boosted its expected economic recovery. In anticipation, longer-term US interest rates have risen rapidly, with the rate on 10-year Treasury securities going from under 1 percent at the start of the year to over 1.75 percent in mid-March. A similar surge has occurred in the United Kingdom. In January and February, interest rates also rose somewhat in the euro area and Japan before central banks there stepped in with easier monetary policy.

Our research in the latest World Economic Outlook finds that for emerging markets, what matters is the reason for the rise in US interest rates.

Emerging and developing economies are viewing rising interest rates with trepidation. Most of them are facing a slower economic recovery than advanced economies because of longer waits for vaccines and limited space for their own fiscal stimulus. Now, capital inflows to emerging markets have shown signs of drying up. The fear is of a repeat of the “taper tantrum” episode of 2013, when indications of an earlier-than-expected tapering of US bond purchases caused a rush of capital outflows from emerging markets.

Are these fears justified? Our research in the latest World Economic Outlook finds that for emerging markets, what matters is the reason for the rise in US interest rates.

Cause and effect

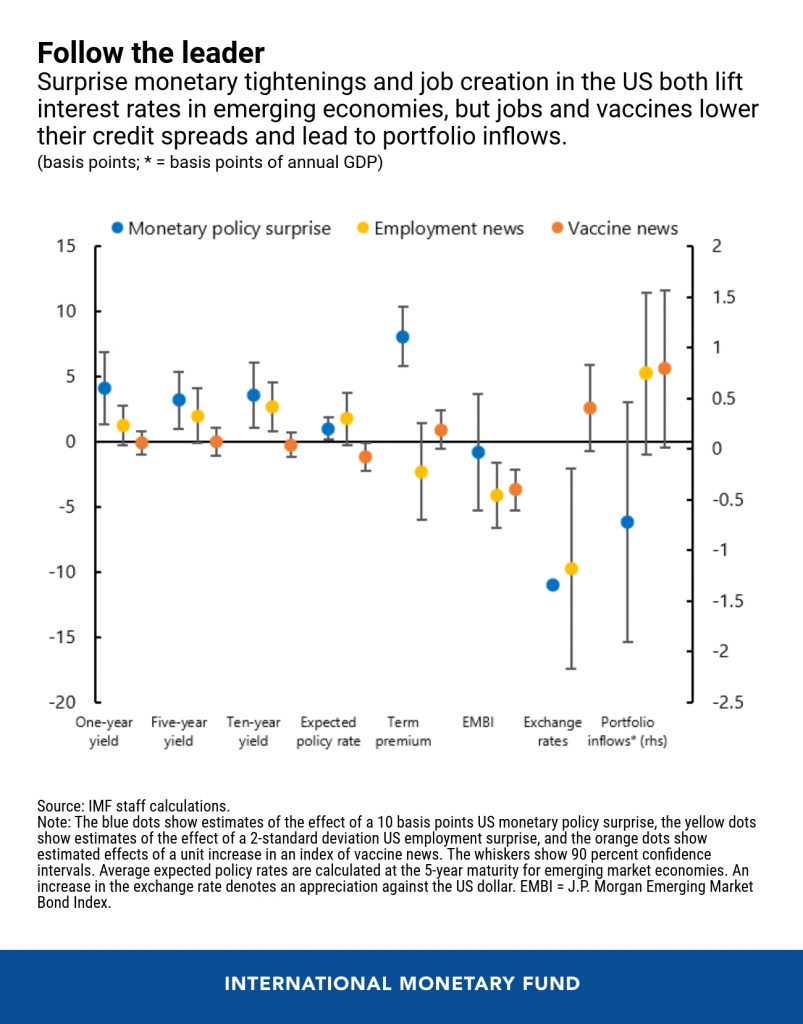

When the reason is good news about US jobs or COVID-19 vaccines, most emerging markets tend to experience stronger portfolio inflows and lower spreads on US dollar-denominated debt. Good economic news in advanced economies could lead to export growth for emerging markets, and the pick-up in economic activity tends naturally to lift their domestic interest rates. The overall impact is benign for the average emerging market. However, countries that export less to the United States yet rely more on external borrowing could feel financial market stress.

When news about higher US inflation drives US interest rates up, this also tends to be benign for emerging markets. Their interest rates, exchange rates and capital flows tend to be unaffected, probably because past inflation surprises have reflected a mix of good economic news, like a higher willingness to spend, and bad news, like higher costs of producing.

When, however, a rise in advanced economy interest rates is driven by expectations of more hawkish central bank actions, it can harm emerging market economies. Our study captures these “monetary policy surprises” as increases in interest rates on days of regular Federal Open Market Committee or European Central Bank Governing Council announcements. We find that each percentage point rise in US interest rates due to a “monetary policy surprise” tends immediately to lift long-term interest rates by a third of a percentage point in the average emerging market, or two-thirds of a percentage point in one with a lower, speculative grade credit rating. All else equal, portfolio capital immediately flows out of emerging markets and their currencies depreciate against the US dollar. A key difference relative to interest rate increases driven by good economic news is that the “term-premium”—compensation for the risks of holding longer-maturity debt—goes up in the US with hawkish monetary policy surprises, and with it, spreads on dollar-denominated emerging market debt.

The good news

In reality, a mix of these reasons is driving up US interest rates. So far, “good news” on economic prospects has been the main factor. Expectations of economic activity in some emerging markets picked up between January and March, which may partly be lifting their interest rates and may help explain the surge in capital flows in January. The subsequent rise in US interest rates has generally been orderly, with markets functioning well. Even as long-term US interest rates have risen, short-term US interest rates have remained near zero. Stock prices remain high, and interest rates on corporate bonds and dollar-denominated emerging market bonds have not diverged from those on US Treasury securities.

Furthermore, market expectations for inflation seem contained near the Federal Reserve’s long-term target of 2 percent a year, and if they stay there, it could help stem the rise in US interest rates. Part of the surge in US interest rates came from the normalization of investor expectations of US inflation.

Tread lightly

However, other factors seem to be at play, too. Much of the increase in US interest rates is due to a rising term premium, which could reflect rising investor uncertainty about inflation and the pace of future debt issuance and central bank bond purchases. The capital outflows from emerging markets that occurred in February and early March turned to inflows in the third week of March, but have since been volatile. It is also unclear whether the large quantities of Treasury securities that the United States is expected to issue this year could crowd out borrowing by some emerging markets.

The situation is therefore fragile. Advanced economy interest rates are still low and could rise further. Investor sentiment regarding emerging market economies could deteriorate. To avoid triggering this, advanced economy central banks can help with clear, transparent communications about future monetary policy under different scenarios. The Federal Reserve’s guidance about its preconditions for a rise in policy rates is a good example. As the recovery continues, further guidance on possible future scenarios would be useful, given that the Federal Reserve’s new monetary policy framework is untested and market participants are uncertain about the pace of future asset purchases.

Emerging markets will only be able to continue providing policy support if domestic inflation is expected to be stable. For example, central banks in Turkey, Russia and Brazil raised interest rates in March to control inflation, while those in Mexico, the Philippines and Thailand kept interest rates on hold.

Ideally, emerging and developing economies should seek to offset some of the higher global interest rates with more accommodative monetary policy at home. For this, they need some autonomy from global financial conditions. The good news is that many central banks in emerging markets were able to ease monetary policy during the pandemic, even in the face of capital flight. Our analysis indicates that economies with more transparent central banks, more rules-based fiscal decision-making and higher credit ratings were able to cut their policy rates by more during the crisis.

Given still-high risk tolerance in global financial markets, and the possibility of further market differentiation in future, now is a good time for emerging market economies to lengthen debt maturities, limit currency mismatches on balance sheets, and more generally take steps to boost financial resilience.

It is also the time to strengthen the global financial safety net—the system of arrangements like swap lines and multilateral lenders that can provide foreign currency to countries in need. The international community needs be ready to help countries in extreme scenarios. The IMF’s precautionary financial facilities can further boost member countries’ buffers against financial volatility, and a new allocation of IMF special drawing rights would also help.

This blog draws on research by Ananta Dua, Philipp Engler, Chanpheng Fizzarotti and Galen Sher, led by Roberto Piazza and supervised by Oya Celasun.