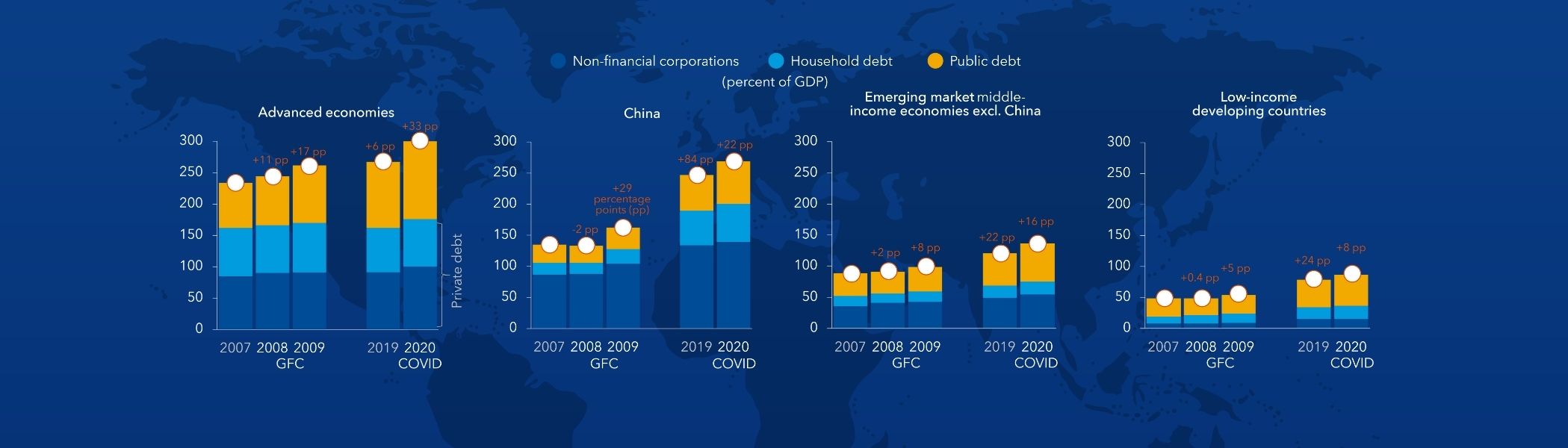

With rising debt vulnerabilities and growing stocks of sovereign domestic debt in emerging and developing economies, the questions of when and how to restructure such debt are now more acute than ever.

Restructuring domestic debt is a tool that can be used by sovereigns facing fiscal and economic stress.

Over the past two decades, emerging market developing economies have seen their share of sovereign domestic debt—let’s call it “domestic debt” for short—increase from 31 to 46 percent of their total sovereign debt. Thus, restructuring of domestic debt is likely to play a role in the resolution of future debt crises. A new IMF paper draws on the past 40 years of sovereign debt restructurings to offer some insights into the key considerations for a domestic debt restructuring that restores debt sustainability while minimizing the disruption caused.

Domestic debt is different

To date, much of the Fund’s and academic work on sovereign debt problems has focused on the implications of restructuring sovereign external debt, by altering the terms of the debt such as the amount owed or the repayment period through negotiations with different types of external creditors. But, as we highlight in the paper, restructuring debt issued under domestic law is different.

On the one hand, domestic debt restructuring may be easier to accomplish. Authorities can, for example, simply elect to alter the terms of debt contracts through changing domestic law. This may avoid some costly consequences associated with external debt restructurings, such as the loss of access to external debt markets.

On the other hand, domestic debt is often held predominantly by domestic creditors who will suffer losses. Through this channel, sovereign debt distress can easily spread to domestic banks, pension funds, households and other parts of the domestic economy. This can add to the economic malaise that made the debt restructuring necessary in the first place.

To restructure, or not to restructure?

The key is to consider the net benefit of a domestic debt restructuring. That is, do the benefits of a lower debt burden outweigh the fiscal and broader economic costs of achieving that debt relief?

The decision to restructure domestic debt or not is always the sovereign’s prerogative and entails the responsibility to limit the damage and help mitigate the effects of a restructuring on the domestic economy. For example, to avoid compromising the viability of the domestic financial system, the government may be required to recapitalize some banks or replenish pension savings. Similarly, ensuring the continued effective functioning of the central bank may require fiscal support.

The net benefit calculation will determine whether or not the domestic debt should be part of a restructuring, together with external debt, or on a standalone basis.

Cast the net wide, be clear and transparent

To garner broad creditor participation in the restructuring and reduce the likelihood of costly litigation, the process of restructuring has to be perceived as fair and transparent.

The scope of claims for inclusion in any domestic debt restructuring—the perimeter—would generally depend on the amount of debt relief needed to restore debt sustainability and the net benefit that can be obtained from each type of claims. In principle, all the government’s domestic debt liabilities could be included. Some creditors may try to use their political influence to protect themselves from burden-sharing, thereby shifting the burden of the adjustment to other creditors. But casting the net wide and relying on voluntary mechanisms may help boost participation in the restructuring by lowering the relief sought from each creditor group.

A strategy that engages creditors constructively and transparently, that relies on market-based incentives, and that presents the debt exchange as part of a consistent macroeconomic plan typically works best. Explaining convincingly how the restructuring fits with the broader strategy of addressing the causes that led to the sovereign debt stress is important to secure the political support needed for a successful operation that restores debt sustainability.

Anticipate and mitigate the damage

The domestic debt restructuring should be designed to anticipate, minimize and manage its impact on the domestic financial system:

- The authorities need to put in place measures that mitigate losses for banks, non-bank institutional investors, and households and that minimize spillovers. For example, the impact on banks can be limited by extending the maturities and/or lowering the interest rate rather than reducing the nominal amount of the outstanding claims. Losses should be recognized early and may need to be paired with a strategy to restore banks’ capital buffers.

- System-wide emergency support that allows institutions to convert illiquid assets into cash may be needed to ensure the functioning of the banking system and shore up confidence. In some cases, temporary measures to slow panic-driven deposit withdrawals and capital outflows might have to be considered.

The authorities should carefully evaluate the potentially adverse consequences of unilaterally amending domestic law. The inclusion and use of collective action clauses in domestic debt contracts could increase legal certainty and predictability, offering a potentially superior restructuring mechanism compared to retrofitting such mechanism by law.

Do it right the first time

Restructuring domestic debt is a tool that can be used by sovereigns facing fiscal and economic stress. To be successful it should be well-designed to avoid doing more harm than good. To ensure that it is done right the first time, sovereign domestic debt restructuring should be part of a broader policy package that effectively addresses the underlying problems and debt vulnerabilities.