We live in dangerous times. The world faces renewed uncertainty, as war comes on top of an ever-changing and persistent pandemic, now in its third year. Moreover, problems that predated COVID-19 have not gone away. When policymakers return to Washington in the coming days for the Spring Meetings of the IMF and World Bank, one of the central topics will be growing debt vulnerabilities in the world.

Debt was already very high before the first coronavirus lockdowns. As the pandemic hit, unprecedented peacetime economic support stabilized financial markets and gradually eased liquidity and credit conditions around the world. In many countries, fiscal policy was able to protect people and firms during the pandemic. It supported monetary policy, too, by adding to aggregate demand and avoiding deflationary dynamics. It all contributed to financial and economic recovery.

Now the war in Ukraine is adding risks to unprecedented levels of public borrowing while the pandemic is still straining many government budgets. The situation highlights the urgent need for authorities to undertake reforms, including governance reforms, to improve debt transparency and strengthen debt management policies and frameworks to reduce risks.

The Fund will continue to help address the root causes of unsafe debt with granular policy advice and capacity-building activities. But, with elevated sovereign debt risks and notable budget and financial constraints, international cooperation to minimize stress during the period ahead will be needed. In cases where liquidity support alone is not enough policymakers need to take a cooperative approach to ease the debt burdens of the most vulnerable countries, foster greater debt sustainability, and balance the interests of debtors and creditors.

Record debt

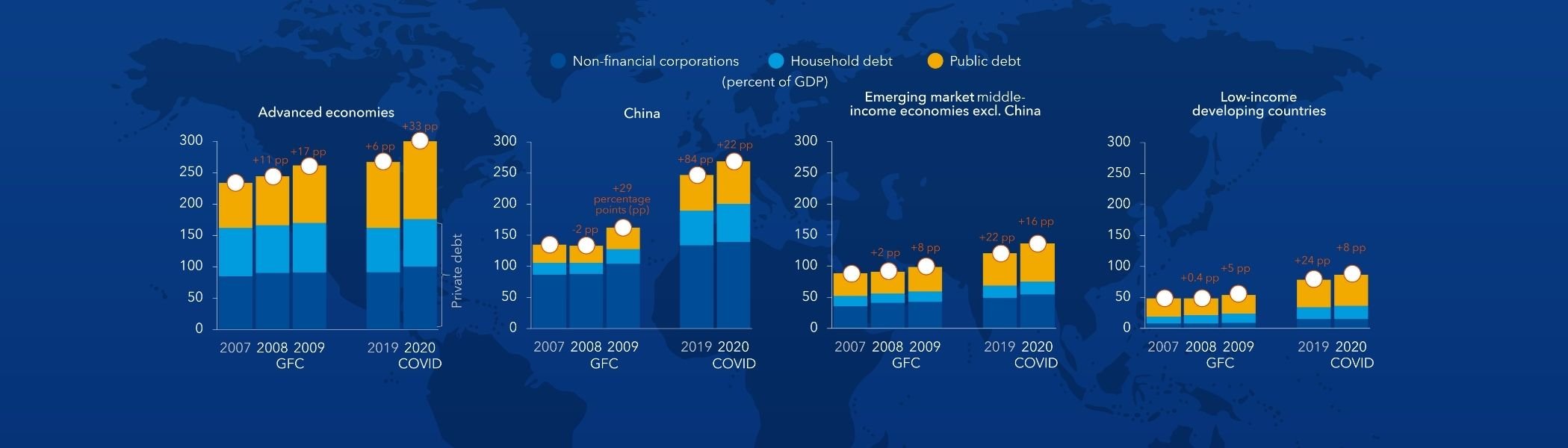

During the pandemic, deficits increased and debt accumulated much faster than they did in the early years of other recessions, including the largest: the Great Depression and the Global Financial Crisis. The scale is comparable only to the two 20th century world wars.

According to the IMF’s Global Debt Database, borrowing jumped by 28 percentage points to 256 percent of gross domestic product in 2020. Government accounted for about half of this increase, with the remainder from non-financial corporations and households. Public debt now represents close to 40 percent of the global total, the most in almost six decades.

Emerging market and developing countries (excluding China) accounted for a relatively small share of the increase. Although their public debt remains far below 1990s levels, debt in these economies has risen steadily in recent years. This partly reflected their ability to tap private markets, increased creditworthiness, and development of their domestic debt markets. Servicing costs have also been on a steep incline. About 60 percent of low-income countries are now in, or at risk of, distress.

Risks from rising inflation

Until recently, low debt service costs assuaged concerns about advanced economies’ record high public debt. There were two elements. First, nominal interest rates were very low. In fact, they were close to zero or even negative all along the yield curve in countries such as Germany, Japan and Switzerland. Second, neutral real interest rates were on a significant downward trend in many economies, including the United States, the euro area, and Japan, as well as a number of emerging markets.

This, combined with real interest rates below real growth rates, contributed to a perception of painless fiscal expansion. However, with heightened risk perception and expected monetary policy tightening, debt vulnerabilities are back in focus.

High public and private borrowing contribute to financial vulnerabilities, which are already concerning. The number of advanced economies with debt ratios larger than the size of their economy has increased significantly. There is a risk that ever-higher levels of debt lead to a widening of interest rate spreads for countries with weaker fundamentals, making it costlier for them to borrow. Moreover, although inflation surprises may lower debt-to-GDP ratios in the short-run, persistent inflation—and inflation volatility—ultimately can raise the cost of borrowing. This process can happen quickly in countries with short debt maturities.

In advanced economies, economic activity, the primary balance, spending, and revenues are projected to return close to pre-pandemic projections by 2024. But the situation in developing countries is much more concerning. Both emerging and low-income economies face persistent GDP and revenue losses. This implies that primary spending will be persistently lower as a consequence of the pandemic, pushing countries further back from reaching the Sustainable Development Goals. That is a matter of global concern.

Sharp increases in energy and food prices are adding to these pressures for the poorest and most vulnerable. Food accounts for up to 60 percent of household consumption in low-income countries. These countries face a unique confluence of factors: dire humanitarian needs intersect with extremely tight financial constraints. For low-income countries that rely on imported fuel and food, the shock may require more grants and highly concessional financing to make ends meet while supporting those households in need.

Global financial conditions are tightening as major central banks raise interest rates to contain inflation. In most emerging markets, sovereign spreads are already above pre-pandemic levels. The credit crunch is exacerbated by declining overseas lending originating from China, which is confronting solvency concerns in the real-estate sector; expanding lockdowns in Shanghai and other major cities; the transition to a new growth model; and problems associated with existing loans to developing countries.

A global cooperative approach

Debt restructurings are likely to become more frequent and will need to address more complex coordination challenges than in the past owing to increased diversity in the creditor landscape. Having mechanisms in place for orderly restructuring is in the best interest of creditors and debtors alike.

For low-income countries, the Debt Service Suspension Initiative expired at the end of 2021. And the Group of Twenty’s Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI has yet to deliver. Improvements are needed. Options should also be explored to help the broader range of emerging and developing economies that are not eligible for the Common Framework but who would likely benefit from a globally cooperative approach in the period ahead. Muddling through will amplify costs and risks to debtors, creditors and, more broadly, global stability and prosperity. In the end, the impact will be most sharply felt by those households that can least afford it.

With sovereign debt risks elevated and financial constraints back at the center of policy concerns, a global cooperative approach is necessary to reach an orderly resolution of debt problems and prevent unnecessary defaults. The views and interests of debtors and creditors must be reflected in a balanced way.