عربي, 中文, Español, Français, 日本語, Português, Русский

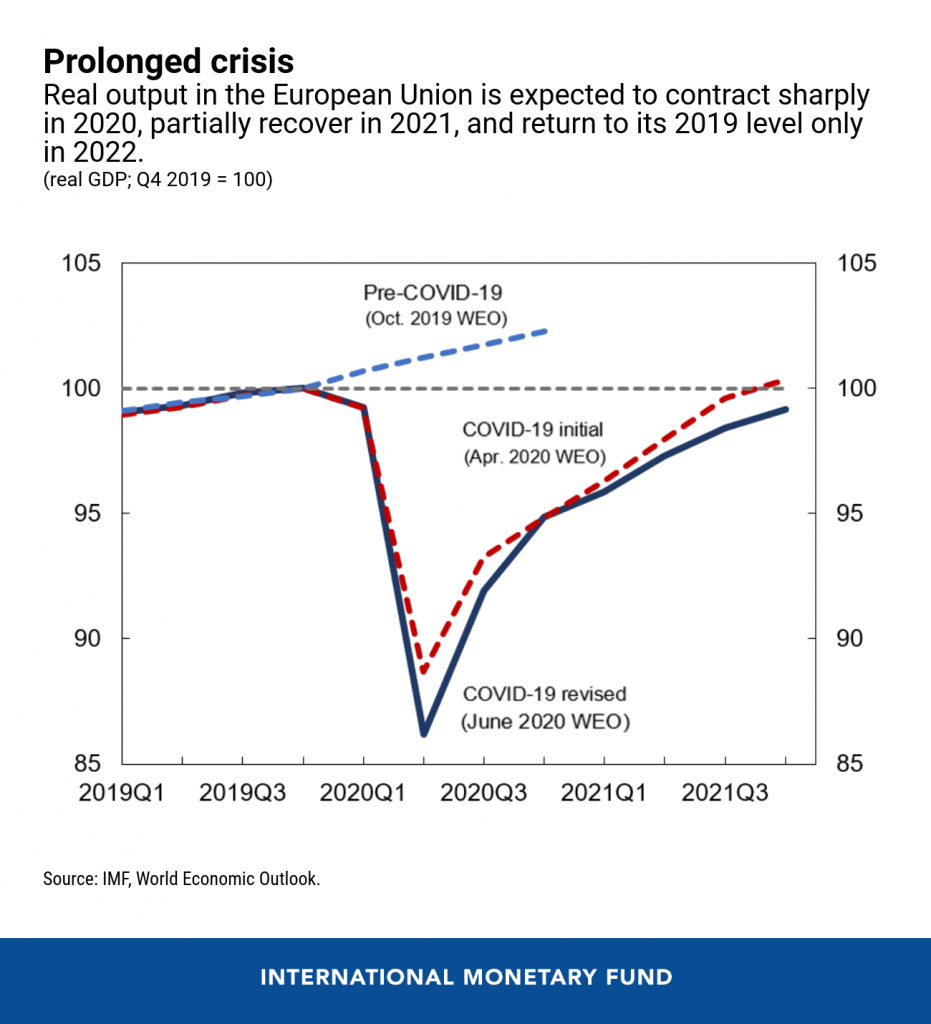

Europe, like the rest of the world, faces an extended crisis. An element of social distancing—mandatory or voluntary—will be with us for as long as this pandemic persists. This, coupled with continued supply chain disruptions and other problems, is prolonging an already difficult situation. Based on updated IMF projections released last month, we now expect real GDP in the European Union to contract by 9.3 percent in 2020 and then grow by 5.7 percent in 2021, returning to its 2019 level only in 2022. If an effective treatment or vaccine for COVID-19 is found, the recovery could be faster—but the opposite would hold true if there are large new waves of infection.

Some European countries will face a tougher recovery path than others. Several went into the crisis with entrenched product and labor market rigidities, holding back their growth potential. Others depend on industries that are tightly integrated into cross-border supply chains, leaving them deeply vulnerable to disruptions of such links. In several large euro area countries, slow growth has coexisted with high public debt and limited fiscal space, constraining the ability to cushion shocks. Inescapably, sharply divergent initial conditions are likely to result in a highly uneven recovery across Europe.

Europe’s high-debt countries will bear the brunt of the social impact. For decades, several of these countries have seen their public debt burdens ratchet up in times of trouble and stabilize—but not fall—in good times. The stepwise pattern of rising debt speaks to a weak record of addressing structural deficiencies, whether due to institutional rigidity or insufficient political will. Results have included high unemployment and emigration, especially among the youth, and a trend toward less-progressive taxation, but pensions have largely been protected. COVID-19—a disease that calls for protection of the elderly but leaves the young shouldering much of the cost—complicates an already difficult demographic situation.

Fiscal policies for a transforming Europe

Against such backdrops, policies—especially national fiscal policies—need to start being repositioned for a longer crisis. At the outset of the pandemic, lockdowns were a vital tool to save lives. To help economic capacity survive a short but extreme disruption and allow activity to promptly bounce back afterwards, fiscal policies were eased sharply. Months later, fiscal support remains as vital as at the onset. But, as dislocations persist, resources will become stretched. Now is the time, therefore, to think ahead and reassess how best to use limited fiscal space without unduly burdening future taxpayers. The longer the slump, the greater will be the need to carefully target support for firms and households in the high-debt countries.

The longer the slump, the greater will be the need to carefully target fiscal support in the high-debt countries.

Policymakers must also recognize that the post-crisis economy may look very different from the economy of 2019. It is becoming clear that we are in the throes of—and that we need—permanent change. COVID-19 has reminded us that nature still reigns supreme, that environmental degradation must stop, and that investing in resilience is good policy. Moreover, prudence requires us to consider that this pandemic could last several years, and may well be followed by future pandemics. Europe must strive for a new, greener economy, one that can operate efficiently even with prolonged social distancing. It may take many years to complete, but transformation needs to be nurtured starting now. We cannot just return to the way things were before.

Change is already underway, with winners and losers. Digitalization has emerged as a key bulwark of resilience, yet also as a divide. Across Europe and beyond, countless employees are adapting to remote work, students to remote learning, doctors and patients to telemedicine, and firms to internet-based sales and door-to-door delivery. Countless others, however, are shut out. Many contact-intensive activities—hospitality, travel, and more—could take years to recover. Some outputs—take coal-fired power or carbon-emitting vehicles—may slip into terminal decline. Again, some countries will be hit harder than others, and inequalities could grow both across and within national borders. We may not yet be able to fully envision the new normal, but the transition has begun.

Public funds must be used to steer the needed resource reallocation while protecting the most vulnerable. In labor and product markets, the focus should be on flexibility, including by ensuring that short-time work schemes that tie workers to their employers are kept temporary. In the corporate sector, support programs must embed incentives that encourage uptake by firms with strong business plans and discourage uptake by firms on a path to failure. As liquidity needs become solvency needs, state aid may need to include equity injections—various European initiatives are already moving this way. Clarity on carbon pricing will also be important to set the stage for a climate-friendly recovery of private investment. Finally, public investment can and should take the lead, focusing on greening, digitalization, and other aspects of resilience.

Given divergent national conditions, there is a strong case for joint EU fiscal action. Supporting the recovery will continue to require substantial fiscal resources. By focusing EU funds on countries hardest hit by the pandemic or with less fiscal space, lower income levels, and greater environmental damage, the “Next Generation EU” package stands to improve outcomes for the single market as a whole. To do so, however, it is vital that it serve as a catalyst and not a substitute for structural reforms and prudent fiscal policies. With fundamental limits to the size of any joint EU assistance, the responsibility for ensuring that debt burdens are sustainable will remain squarely at the national level. Even with low borrowing costs, all countries will need to partner upfront stimulus provision with credible medium-term policy plans.

Preserving financial stability and the supply of credit

Through the acute crisis phase and beyond, monetary policy will need to remain strongly accommodative. With crisis-related demand shortfalls further weakening the inflation outlook, central banks must continue to deliver substantial stimulus and ensure that financial markets remain liquid. In practice, this means policy rates must remain at extraordinarily low levels for now, supported by net asset purchases that implicitly look to bond spreads and issuance volumes. Once the period of stress has passed, however, there will be a need for introspection—reflecting on the many years of missed inflation objectives, on how to properly demarcate monetary policy from fiscal policy, on the global decline in equilibrium real interest rates as savings outpace investment, on the choice of monetary instruments, and more. The European Central Bank’s strategic review remains as essential as ever.

Finally, another key priority in the coming period will be to ensure an uninterrupted supply of bank credit to the economy. History has taught us that, when efficient savings allocation breaks down, crises tend to last longer. For now, most European banks have the capital and liquidity they need to expand credit. But, as this crisis wears on, there will be many defaults, and these could erode bank buffers and lending capacity. Potentially, therefore, one feedback loop of this crisis may simply be time: the longer the pandemic, the greater the credit disruption, and the slower the post-pandemic recovery. It is vital that supervisors prepare banks for the coming test. Robust lending standards must be upheld, losses provisioned for fully and transparently, and restructurings of bad assets pursued actively to preserve value. In some cases, bank recapitalization may prove necessary.

A calibrated policy mix

With many difficult challenges lying in wait, managing this vast crisis will call for an increasingly calibrated approach going forward. The initial emphasis on opening the fiscal and monetary floodgates had its place. As time passes, however, policymakers must reflect also on longer-term considerations. Even as low borrowing costs soften some of the tradeoffs, responsible policymaking will still need to weigh immediate imperatives against future burdens on young taxpayers and new generations. Difficult reforms must be pursued with renewed determination.

The overarching policy goals are not one, but two: to save lives now, and to ensure that Europe emerges with a greener and safer economy for the long run, one where future generations can thrive equitably.