Uncharted Territory

Finance & Development, June 2009, Volume 46, Number 2

When aggressive monetary policy combats a crisis.

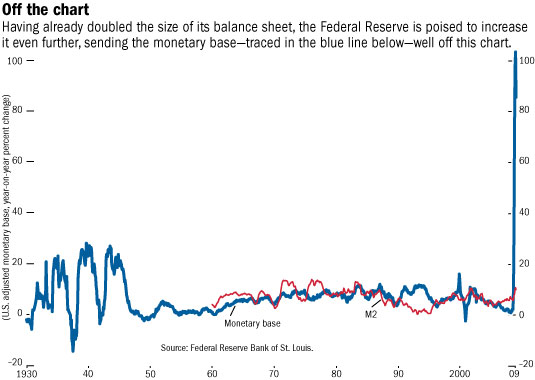

The current global economic downturn will probably not be as severe as the Great Depression, partly because of the vigorous response from the world’s policymakers. Eighty years ago, policymakers were initially not even convinced of the need to ease monetary conditions, and they bear a good part of the blame for the ensuing depression. This chart shows how radically policy thinking has changed since then.

When the crisis began in mid-2007, the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) reacted by aggressively cutting its target for the policy interest rate—the fed funds rate, at which banks lend to each other overnight—and introducing special facilities to ensure that all parts of the financial system had access to liquidity. At the same time, too much money in the system would push the fed funds rate below target and possibly stoke inflation, so the Fed sold U.S. Treasury securities to mop up liquidity.

Following the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, financial and economic conditions worsened dramatically. The Fed cut the policy rate further, introduced yet more facilities, and now allowed its balance sheet to more than double in size over just a few months, pumping up bank reserves and thus the monetary base. Broader monetary aggregates, however, increased only modestly, given banks’ cautious behavior.

The expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet made it difficult to maintain the fed funds rate near the policy target, and in December 2008 the Fed dropped the target to a range of 0 to 25 basis points. Although there is no more scope for interest rate cuts, the Fed retains the ability to conduct monetary policy through changes in the composition and size of its balance sheet. And this ability is crucial, given the threat of deflation.

Great Depression, great rethink

The Fed tightened policy in 1930, helping to trigger the Great Depression, and in 1937 it put the brakes on too early, killing off the recovery and sending the economy into recession. In between, it did expand the money supply, but far less aggressively than today’s Fed has chosen to do.

Finance to wage a world war

The Federal Reserve bought Treasury debt during World War II, when the government had to borrow on a large scale to finance its greatly expanded defense budget. With the Fed helping to finance record-high budget deficits, the monetary base endured some sharp swings during the 1940s, but nothing like the increase during fall 2008.

Off the chart

Having already doubled the size of its balance sheet, the Fed is now poised to increase it even further, sending the monetary base (the blue line) well into another page on top of this one. In March 2009, the Fed announced that it would massively increase its purchases of mortgage-backed securities and debt issued by U.S. housing agencies Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and start to buy long-term U.S. Treasury bonds. These purchases have already begun but could go much further.

Exit this way

There is little doubt that the Fed’s dramatic expansion of the monetary base has been justified given the sharp economic downturn and the risk of deflation. But the exit strategy could be difficult.

Once the economy starts recovering, and banks no longer feel so reluctant to lend their reserves, the Fed will need to shrink the monetary base quickly to forestall inflation. Knowing the right time to do this is, of course, tricky.

But even if it’s obvious when to start shrinking the money supply, how to do it may be less evident, since the Fed now has some assets on its balance sheet that are relatively long term and illiquid and thus not easy to sell off quickly. The Fed is considering a range of policy options—some of which would require new legal authority—to address this issue.

It’s basically cash

The fat blue line in the chart shows the annual growth in the adjusted U.S. monetary base—that is, the amount of cash in the economy, and banks’ reserves that could be lent and spent too. Apart from a spike as the year 2000 arrived, when people feared computer systems would go down and hoarded cash, growth in the U.S. monetary base was fairly steady from World War II until late in 2008.

The thinner red line in the chart shows why there is no imminent threat of inflation despite the explosion of the monetary base. All that money pumped into banks’ reserves has stayed right there: in the banks’ vaults. The thin red line shows the trend in M2, which is the monetary base in the blue line plus what’s in personal and corporate checking and savings accounts. This broader measure of money has been increasing only modestly.

Watch out for falling prices

Consumers like lower prices on the things they buy. But if prices fall across the board, and keep falling—a trend known as deflation—the economy risks a dangerous downward spiral. Why? Because deflation makes borrowing look expensive even at very low interest rates, leading to less investment, lower growth, and thus even softer prices. And because deflation makes repaying consumer debt seem more expensive, making people feel poorer and spend less which, in turn, fosters further price declines. And finally, because deflation may cause consumers to delay purchases in the hope of paying less later. But if all buyers stay on the sidelines, prices will decline even more, and the economy can enter a vicious circle. Avoiding such an outcome is paramount and helps explain why the Fed has boosted the monetary base as shown in the chart. It’s also a major reason why governments across the world have enacted large fiscal stimulus packages.