Youth in the Balance

Finance & Development, March 2012, Vol. 49, No. 1

PDF version

![]() IMF podcast: Combating youth

IMF podcast: Combating youth

unemployment in Africa

Frustrated and angry, the world’s young people are demanding change

FROM the unemployment lines of Europe and Japan to the swarming streets of Cairo and Lagos, the world’s youth are feeling the pinch of the global economic crisis and are demanding change.

Whether it’s the “Occupy Wall Street” movement in the United States or the mass rallies of the Arab world, young people have been jolted into action and are leading the response to diminished opportunities and unfulfilled aspirations.

Politicians around the world are recognizing that the prolonged global crisis is shattering hopes, building tensions, and fostering protests. In many instances, young people have played key roles in agitating for change, but the reforms they are calling for speak to society as a whole, not just to their generation.

Resilient and connected

The global economic crisis, prolonged by strains within the euro area, has put millions of youth out of work—50 percent in Spain and Greece and 30 percent in Portugal and Italy. It threatens to spawn a “lost generation” that may find it hard to recover, and it is likely to exact a harsh human toll for years to come.

The young are naturally resilient and tend to have fewer dependents than older generations. But those who are out of a job for a long time often see their self-confidence and skills erode and lose their attachment to the labor force (see “The Tragedy of Unemployment,” in the December 2010 issue of F&D). They can become disheartened, disempowered, and disconnected from established institutions (see “Voices of Youth,” in this issue of F&D).

Yet clearly, in the long run, it is today’s young people who will face the task of creating economic success and human security.

Allowing youth to take the lead will mean of course ensuring that they have a good education and good health. In some countries, a declining share of young people in the population will make it easier to spend more resources on them. In others, where youth represent a rising fraction of the population, the reverse will be true. And in many countries, competition for resources is on the horizon, as an aging population, after decades of contribution, sees itself at risk and demands more attention (see “The Price of Maturity,” in the June 2011 issue of F&D).

Amid the turmoil and the uncertainty about their economic future, young people, more than any other group, have turned to new media for information and to communicate with their peers and beyond. Widespread access to the Internet has raised their aspirations, in part by making the young aware of the vast differences in standards of living within their countries and around the world. It has also made them more conscious of the extent of corruption and injustice and how that affects their lives.

This greater awareness on the part of youth, arising in the context of recession and scant opportunities, portends a potentially shaky long-term economic future. As such, young people (and others) may well have reason to up the ante in their protests in coming years. Moreover, it seems likely that the social and political movements that gain traction in one place may inspire others around the world, as they did in Tunisia, for example.

How big is this issue?

More than one in six people in the world are between the ages of 15 and 24. Yet the world’s 1.2 billion adolescents and young adults are probably the most neglected—by policy analysts, business thinkers, and academic researchers—of all the age groups. Not only have the 810 million people over the age of 60, whose growing numbers threaten social safety nets around the world, attracted more attention, so have children and prime-age adults.

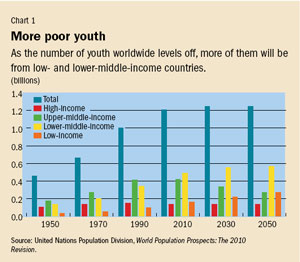

That neglect is surprising. Adolescents and young adults are powerful agents of change in society. Their skills, habits, behavior, and ambitions in such diverse realms as work, saving, spending, rural-to-urban and international migration, and reproduction will profoundly shape society for years to come. Their global numbers have been steadily increasing since 1950 and will continue to do so for at least another two decades (see Chart 1).

The current and future generations of youth present countries with both great peril and great promise. Whether they can lead productive lives as adults depends much on what they experience in their school years and in their earliest years of work.

The number of adolescents and young adults and their share of the total population reflect trajectories of birth and death rates and, to a lesser extent, international migration—and are closely connected to the demographic transition, a term demographers use to signify a long-term change from high to low mortality and fertility (i.e., the number of children per women; see box). Because fertility rates initially decline more slowly than do mortality rates, this transition brings first an increase in the number of children followed by a surge in the number and share of those ages 15 to 24.

Parsing the projections

All population data and projections are the medium-fertility estimates published in World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision by the United Nations Population Division. The projections depend critically on assumptions and projections of future fertility, mortality, and migration. For the world as a whole, the medium-fertility trajectory declines smoothly from the current level of 2.5 children per woman to 2.2 in 2050. This change represents the net effect of fertility declines in 139 economies and increases in 58.

Estimates of future life expectancy are based on historical country- and gender-specific trends and a model that anticipates more rapid gains in countries with lower current life expectancy.

Assumptions about migration are based on past estimates and the policies that countries have adopted. Projected levels of net migration incorporate a slow decline through 2100.

The United Nations Population Division provides the income-group population data on a DVD, World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision, Special Aggregations. Income groupings are based on criteria from the World Bank World Development Indicators, 2011. These criteria, expressed in 2009 per capita gross national income (GDP plus net income from abroad), are

•low-income: $1,005 or less;

•lower-middle-income: $1,006 to $3,975;

•upper-middle-income: $3,976 to $12,275; and

•high-income: $12,276 or more.

Behind the numbers

Let’s take a look behind the numbers at some key factors driving the frustration of the young.

The economic issues related to young people include employment, income, savings, spending, affordable higher education, and taxation that may disproportionately benefit older groups. The social issues encompass cohabitation, marriage, divorce, fertility, gender equity, crime, and intergroup relations. The political issues concern trust and engagement in formal and informal political institutions and with leaders.

Future population health is also at risk. Today’s youths—tomorrow’s workers—will not necessarily be more healthy and productive than their parents. The decline in physical activity (a consequence of urbanization and a transition to more sedentary occupations) and rising obesity and alcohol and tobacco consumption portend more noncommunicable diseases such as cardiovascular problems, diabetes, and cancer. And less stability—at home and on the job—has negative implications for the emotional and mental health of the world’s young people.

A rising adolescent and youth share of the population signals increases in the productive capacity of an economy on a per capita basis in the years to come and the prospect of a demographic dividend, a time-limited window of opportunity for rapid income growth and poverty reduction (Bloom, 2011). The window, which exists as long as the working-age share of the population is relatively high, also poses a risk of social and political instability in economies that fail to generate sufficient jobs.

It is no surprise that many of the participants in recent protest movements have been young people—both in societies where youth unemployment has always been high and in advanced economies where the global economic crisis has hit younger workers the hardest. Youth have a huge stake in bringing about a political and economic system that heeds their aspirations, addresses their need for a decent standard of living, and offers them hope for the future.

The absence of such a system is a potent recipe for conflict—especially now, with the availability of cheap means of communication such as smartphones and social media.

Vulnerable in crises

Adolescents and young adults are especially vulnerable to macroeconomic downturns, and have borne the brunt of the global economic crisis that began in 2008 and the subsequent sluggish employment recovery. The global youth unemployment rate rose from 11.6 percent to 12.7 percent between 2007 and 2011, while the youth labor force participation rate (the percentage of the age group either working or looking for work) showed a modest decline as some discouraged workers gave up their job search (ILO, 2012).

Developed economies experienced the largest effects (see “Scarred Generation,” in this issue of F&D): youth unemployment in these countries rose more sharply than unemployment among those 25 and older (especially among males). Youth unemployment has stayed high, and the slower the recovery, the less likely it is that young people will develop a fruitful connection to the labor market.

On the other hand, young people will inevitably play a key role in the recovery thanks to their dynamism and willingness to relocate from labor-surplus to labor-shortage areas, and from low-productivity agriculture to higher-productivity industry and services. Their up-to-date training and education is also often a plus—although too often the education system imparts skills that are out of date or unneeded (see “Making the Grade,” in this issue of F&D). Insofar as the expectations that education typically creates are not satisfied, youth can also power a decisive impulse to change institutions and leadership.

Country examples

Some examples help illustrate what is happening.

India is an example of a country focused on and struggling to realize the benefits of its large and still-growing youthful population.

It is the second most populous country in the world, and its 15- to 24-year-old population is the largest—and growing. (India’s 238 million 15- to 24-year-olds equals the total population of the world’s fourth most populous country, Indonesia). The Indian National Knowledge Commission, headed by Sam Pitroda, concluded, “Our youth can be an asset only if we invest in their capabilities. A knowledge-driven generation will be an asset. Denied this investment, it will become a social and economic liability.” India’s young people have shown strong support for social activist Anna Hazare and his anticorruption campaign—a testament to their acute awareness of the debilitating effects of corruption.

Neighboring Pakistan sits on a similar precipice, albeit a bit closer to the edge. With 38 million adolescents and young adults, Pakistan has the world’s fifth largest 15- to 24-year-old population. But fragile governance structures, a poor record of development progress, regular episodes of extreme social conflict, and a shaky macroeconomic situation all contribute to young people’s lack of confidence in Pakistan’s future (British Council, 2009). These conditions can be high-octane fuel for repeated cycles of social and political instability. If, however, Pakistan invests in the talents and productive capacity of its young and channels their energy, it could step onto a development trajectory that will allow the country to regain some of the ground lost in recent decades and that better satisfies the aspirations of its people.

Similar circumstances helped crystallize the Arab Spring protests, demonstrations, and uprisings that began in December 2010 and led to the fall of governments in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya and to ongoing conflict elsewhere in the Middle East, North Africa, and beyond. These events are rooted in a multitude of social, cultural, political, and economic factors, but large populations of unemployed, underemployed, and unmarried young people are often considered to be a common denominator. The thinking is that those who are unemployed and unmarried have relatively little to lose and relatively more to gain from change. In addition, new social media—such as Facebook and Twitter, which have taken strongest hold among the young—facilitate communication and organizing. Although the theory is intriguing, empirical evidence of the predictive power of youth demographics with respect to the nature and intensity of social and political unrest—and its practical consequences—is still in its infancy (Hvistendhal, 2011).

In Africa, the youth spotlight is often focused on the continent’s largest population: that of Nigeria. In 1980, Nigeria’s GDP per capita was slightly higher than that of Indonesia, but today it is only half that. Demographic factors appear to be a powerful contributor to this divergence in macroeconomic performance (Okonjo-Iweala and others, 2010). The demographic transition was much more rapid in Indonesia than in Nigeria, resulting in a larger share of adolescents and young adults in the African nation. Indonesia used much of its oil revenue to educate its youth. It successfully absorbed its young people into productive employment and elevated their standard of living. Nigeria could benefit from careful study of Indonesia’s example.

There are currently 32 million Nigerians ages 15 to 24, and more than double that number under the age of 15. These age groups represent a huge national resource. Investments in their skills and health, and in the physical capital, infrastructure, and institutions that will make them productive, will help determine Nigeria’s development success. Investing in girls and women, including investments in reproductive health, would likely have the added benefit of lowering fertility rates and freeing up resources for social investment. Failure to satisfy the desire of youth for productive engagement could further undermine political legitimacy, promote frustration and conflict, and deter investment. Like many other countries, Nigeria must also stay attuned to inequalities across geographic units and religious and ethnic groups and adopt policies to keep these from becoming a source of friction and instability.

Change on the way

The demographic weight of young people is slated to change, however. And this will have important implications—for their future and that of the global economy.

Young people are more highly represented in countries and regions where the demographic transition has been sluggish. For example, young people account for 12 percent of the population in high-income countries and in Europe, whereas they make up about 20 percent of the population in low-income countries and in Africa. But the brisk annual average rate at which the age group has been growing since 1970, 1.4 percent, will essentially end in coming decades—dropping to less than 0.1 percent from 2012 to 2050.

During that period, the share of total population that adolescents and young adults have maintained during past decades will diminish as their tepid growth rate is dwarfed by an overall population growth rate of 0.73 percent.

The global figures, however, mask considerable underlying diversity. Swaziland has the highest share of 15- to 24-year-olds, 24.5 percent of the total population and nearly two and a half times the fraction in Japan (9.7 percent), Spain and Italy (9.8 percent), and Greece (10.1 percent).

In high-income countries the number of 15- to 24-year-olds is already stagnant or declining. By contrast, the number of adolescents and young adults has been growing at breakneck speed in low-income countries (2.6 percent), lower-middle-income countries (2.1 percent), and Africa (2.7 percent). But that will end in the low-income countries soon.

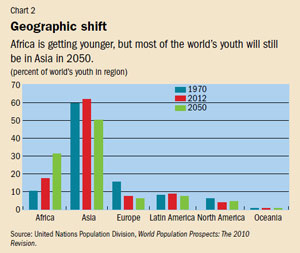

In coming years, the rate of increase in the number of 15- to 24-year-olds will decline in every income group and geographic region. The rate will turn (or become more) negative in the upper-middle-income countries and in three regions—Asia, Latin America, and Europe (see Charts 1 and 2). The steady increase in the number of 15- to 24-year-olds from 1950 through 2010 will abate and plateau at 1.26 billion around 2035. Only in low- and lower-middle-income countries will the number of adolescents and young adults continue to increase.

With these changes, the concentration of adolescents and young adults in the world will move sharply in the direction of Africa. Currently, Africa is home to 17.5 percent of the world’s adolescents and young adults, while Asia accounts for 61.9 percent. But by 2050, Africa’s share of the world’s adolescents and young adults is projected to grow to 31.3 percent, while Asia’s is projected to drop to 50.4 percent.

Elderly on the rise

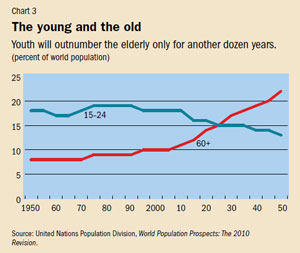

Moreover, adolescents and young adults will not outnumber the elderly for much longer (see Chart 3).

According to projections by the United Nations Population Division, slower growth in the number of 15- to 24-year-olds, coupled with more rapid growth of those ages 60 and over, will result in a crossover of the numbers in 2026, when the elderly will outnumber the young. The crossover has already occurred in the high-income countries (1990), Europe (1982), North America (1987), and Oceania (2011). It is projected to occur in the upper-middle-income countries by the beginning of the next decade, and in Asia not long after.

As noted above, India has the largest number of people between 15 and 24—238 million—and its youth dominance will increase in the coming decades. That’s because in China, today the world’s most populous country, the number of 15- to 24-year-olds will shrink from the current 217 million to 158 million in 2030.

Large adolescent and youth populations today do not signal further growth in the future. Among the 10 countries with the highest 15- to 24-year-old populations in 2012, in 5 the youth population is projected to increase by 2030 and in 5 this age group is projected to decrease. Among all countries, the fastest growth of 15- to 24-year-olds will take place in sub-Saharan Africa—Niger, Zambia, Tanzania, Uganda, and Malawi—while the biggest growth rate declines will be in Bosnia and Herzegovina (–2.4 percent), Albania and Moldova (–2.3 percent), and Cuba (–2.2 percent).

What is to be done?

Where does all this take us? As we have seen, youth can instigate change, and they and others can benefit, but that means getting many things right in a number of realms.

Perhaps first and foremost are improvements in training and education (at all levels, in both access and quality). This will not be easy, but it is clear that new thinking (and probably new resources) is needed in many countries, so that young people are educated more thoroughly and in ways that benefit themselves and their economies.

Mandatory or volunteer service programs—ranging from national military service to volunteer organizations such as the U.S. Peace Corps—can socialize young people, instill a sense of community, and boost self esteem, while imparting marketable skills. It would be useful to expand apprenticeships in some situations, specifically targeting youth and not those over age 25 as often happens now in the United Kingdom. And more emphasis on cultivating financial literacy, health literacy, and entrepreneurial skills would likely pay good dividends.

Other priorities include provision of reliable and modern infrastructure, more carefully tuned labor market policies, greater access to financial markets, governance that takes youth issues into account, and universal health care. This last point is key. Good health is as important as education and training in allowing young people to enhance the skills they need to become economically productive members of society. Youth, like all other groups, need access to quality health care services if they are to realize their potential.

Benefiting from the dynamism of youth also means addressing the challenges of gender, income, and rural-urban disparities, and managing the expectations of young people. In addition, it means dealing with the weakening of family units—in part by figuring out how to move jobs to where people live and thus lessening economically driven migration of younger family members.

Carrying out these steps is not, however, sufficient to ensure a productive future for the world’s youth. That requires the creation of good jobs—and efficient mechanisms to connect people with those jobs—and ensuring that the young are deeply integrated into the fabric of society and share equitably in all its resources and in the benefits they confer.

The political weight of adolescents and young adults is already declining in the high-income countries and in parts of Latin America and Asia. It will also wane in many developing countries in the decades ahead as their populations begin to age. But it is undoubtedly the case that the elderly in all countries will be better supported in the future if more resources are invested in adolescents and young adults along the way.

Finally, it is important that institutions, policymakers, and society as a whole really listen to what young people are saying. Communities, cities, provinces, and countries can set up forums for the purpose of listening to the concerns and ideas of adolescents and young adults and stimulating change. Young people could be offered a voice in decision-making bodies. To make such processes genuinely worthwhile means including a true cross section of this demographic group, by inviting, for example, individuals who represent poor or less-educated sectors of society. Inclusion can benefit all. ■

References

Bloom, David E., 2011, “7 Billion and Counting,” Science, Vol. 33, No. 6042, pp. 562–69.

British Council, 2009, Pakistan: The Next Generation (Islamabad).

Hvistendhal, Mara, 2011, “Young and Restless Can Be a Volatile Mix,” Science, Vol. 33, No. 6042, pp. 552–54.

International Labor Organization (ILO), 2012, Global Employment Trends 2012: Preventing a Deeper Jobs Crisis (Geneva).

Okonjo-Iweala, Ngozi, David E. Bloom, and others, 2010, Nigeria: The Next Generation Report (British Council and Harvard School of Public Health).