Can Women Save Japan (and Asia Too)?

Finance & Development, October 2012, Vol. 49, No. 3

Government policies that support women in their work-family balancing act would help Japan remain a player in the global economy

“IT is very difficult for women in Japan to balance raising children and working full-time,” says Naomi Nakamura, a 35-year-old physical therapist from Yokohama who is now on maternity leave looking after her four-month-old baby girl. “Many companies do not allow shorter working hours, and even if they do, female employees are often reluctant to work part-time because of the atmosphere at work,” explains Nakamura, who also has a three-year-old son.

For Nakamura, work, child rearing, and home are literally a balancing act. After her son was born, Nakamura was lucky to find a day care center near her job, but she still had a 20-minute bike ride to work with her son on the back. She tried to find an educational day care center for her son but, with none available, she had to put him in a center that provides only child care. She shopped for her groceries on her way home, putting the groceries in a basket at the front of her bike and her son in a seat on the back.

Like most Japanese fathers, Nakamura’s husband works late every night, so she feeds the children, bathes them, and puts them to bed herself. She then cooks dinner for herself and her husband. They eat late at night and go to bed exhausted.

She struggled to find a child care center for her son and felt uncomfortable leaving the office early if the center called because he was sick. Before she went on maternity leave, her husband usually took their son to the center in the morning and she picked him up in the evening. But when her husband was on a business trip, which happened quite often, both tasks fell to Nakamura. “I feel very sorry for my colleagues who have to do extra work when I have to leave the office,” she says.

Still, Nakamura feels lucky compared with her friends because her job skills are in demand. Many of her friends are being told they cannot have their old jobs back or are struggling to find part-time work because employers look askance at someone who may have to take leave to care for a sick child.

Nakamura’s story is common to many women across Japan and in parts of Asia. Their daily struggles balancing work and home are so daunting that many feel they have to choose between raising children and building a career.

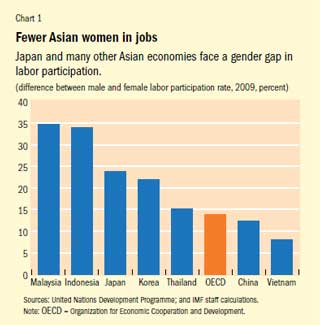

As a result, in many Asian economies fewer women work outside the home than in comparator economies. The female labor participation rate in Japan is 24 percentage points lower than that of males, and in Korea it is nearly 22 percentage points lower (see Chart 1). In certain emerging market Asian economies, such as Malaysia and Indonesia, the gap is even higher. In China and Vietnam, in contrast, the differences are less pronounced, due in part to societal preferences.

In our research on differences in female labor participation both across and within countries over time, we find that both demographic shifts and government policy are important factors in explaining the difference in participation rates. We also find that Japan (and other Asian countries) can do much to remove barriers to increase women’s labor force participation and thereby help mitigate the impact of an aging population on national income.

Feminine trends

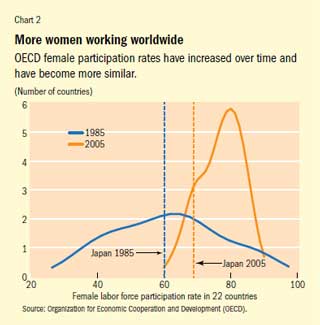

Participation rates in countries that are members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) increased on average from 61 percent to 77 percent between 1985 and 2005 (see Chart 2). Participation rates have also started to converge: countries that started out with lower participation rates are catching up to those with more evenly balanced workforces. These changes have largely come hand in hand with increased social acceptance of women in the workplace. But two other factors also stand out.

First, more women are now attaining higher education than in the past, which increases their potential lifetime earnings and strengthens their attachment to the labor market. In fact, in many countries women are now, on average, more educated than their male counterparts. At Seoul National University, for example, the ratio of female undergraduates increased from about one-fourth of the student body to about one-half just in the past decade. This increase in female education has put more women in the workplace and made them less willing to focus on caring for children to the exclusion of a career.

Second, women around the world are getting married later in life and are choosing to have fewer children. As a result, many women have established careers before they have to make a choice about whether to stay home. And fewer children means the demands of maintaining a household and child rearing are less daunting, allowing women more choice about work–home life balance—choices not available to them in the past.

Still, demographics do not explain all the variation across countries. Policies also make a difference.

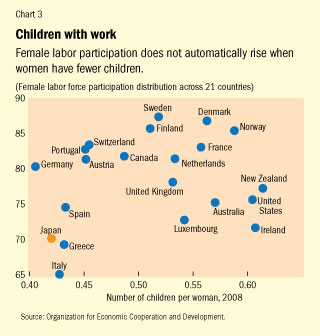

A look at the relationship between fertility rates and female labor participation across countries in recent years shows the importance of policy. Although lower fertility rates might be expected to accompany higher female labor participation, the relationship is actually much more complicated (see Chart 3). This suggests—as is substantiated by our empirical analysis—that government policy matters too. Indeed, the countries with the most generous child-rearing policies have some of the highest fertility rates (excluding countries with high immigration) and the highest rates of female labor market participation. Government policies with a positive impact include expenditures on child care, parental leave, and the removal of dated tax codes that penalize the income of second earners.

Flexible environment

Nakamura finds it difficult to balance work and child-rearing responsibilities. She says it would be impossible for her to raise her two children and work if she could not count on her mother, who lives an hour and a half away, to take care of her children when she has day care problems but has to work. It is difficult in Japan to hire babysitters or nannies.

In a 2010 survey of Japanese women by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication, 34 percent of respondents cited housework and 14 percent working hours as the primary reason they were not participating in the workforce. A similar survey in Korea, by the Ministry of Labor in 2007, found that for 60 percent of the women surveyed, child rearing was the biggest obstacle to participating in the labor force. The difficulties of this balancing act are reflected in the sharp drop-off in labor participation rates of women in their late twenties and early thirties. This is particularly true in Japan, even though its labor participation rate for women at the start of their careers is as high as in comparator countries.

Government policy has made a difference in many northern European countries. In Sweden, for example, the government has established a comprehensive parental leave policy, a highly subsidized child care system, and a strict policy of shorter working hours for women. These systems have resulted in high rates—over 90 percent—of women returning to the workforce following childbirth. In the Netherlands, meanwhile, the emphasis has been on making part-time work as attractive as full-time work, with comparable hourly wages, benefits, and employment protection. This is an important lesson for Japan and Korea, where the increasing prevalence of dual labor markets—favoring insiders over new participants—could be discouraging potential part-time workers, who tend to be women with family responsibilities, from entering the labor force.

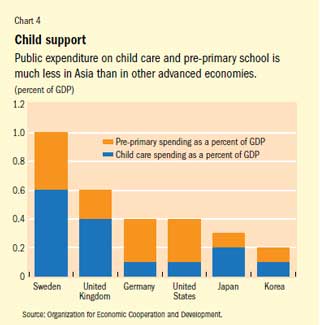

The importance of government policy is further confirmed by our empirical work; perhaps unsurprisingly we find that parental leave policies and government expenditures on child care, among other supportive policies, are strongly correlated with high female labor participation. In Asia, however, governments tend to provide much fewer such benefits (see Chart 4). In part, this reflects Asian countries’ level of economic development, but even in Asia’s most advanced economies, there is a benefit gap. Sweden’s expenditures on child care are three times higher than Japan’s and five times higher than Korea’s.

Model behavior

The other striking aspect for Asia’s women is the paucity of female managers in Japan and Korea (only 9 percent), relative to 43 percent in the United States (see Chart 5). Indonesia and China do not fare much better, at 14 and 17 percent, respectively. Thailand, on the other hand, performs relatively well, with 29 percent female managers, just below the OECD average.

The lack of female managers is due not only to low female labor participation rates, but also to a system—in some countries—that discourages women from entering career-stream positions. In Japan, for example, only 6 percent of career-track employees are female. Nakamura knew at an early age that she wanted to work as well as have children, and so she began carefully planning her career while still in high school. She decided to acquire a profession specialization (with a license or certificate) that would allow her to compete equally with men. But, she says, some women might like to have a choice between a full-time professional position and a less stressful non-career-oriented job.

Self-selection into non-career-track positions is another possible reason for the small number of women managers. This process appears to start early on, with gender ratios in top universities already showing divergence. At the University of Tokyo, for example, where entrance is based on test outcomes, less than 20 percent of the student body is female.

Raising the number of women in high-profile positions would encourage others to mirror that behavior by choosing career-track jobs. There are some signs that things are changing: the Bank of Japan appointed its first female branch manager in 2010; Daiwa Securities placed four women on its board of about 50 members in 2009; and in 2010, Shiseido set a goal of 30 percent female managers by 2013. Politicians in Korea have considered establishing laws on the minimum proportion of female directors that must serve on corporate boards, as is now under consideration in the European Union.

Women to the rescue

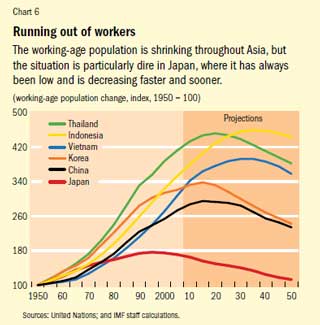

Raising female labor participation rates not only improves gender equality but also helps boost and maintain growth rates across Asia. Societies around the world are increasingly struggling with the consequences of population aging (see “Wising Up to the Cost of Aging,” in the June 2011 issue of F&D). As a result, countries will need to make the best use of limited resources, including their own citizens. In Japan, the size of the working-age population, ages 15–64 is projected to fall from its peak of 87 million in 1995 to about 55 million in 2050—approximately the same size as the Japanese workforce at the end of World War II (see Chart 6). This decline in the labor force is sharpest among advanced economies, though other Asian economies are not far behind; steep declines are predicted soon in Korea and China too.

Aging societies could even see the size of their economies shrink if the current fast pace of productivity growth does not continue to outstrip the decline in the number of workers. In Japan, where the negative impact from aging on growth has been larger than in any other advanced economy, the decline in labor is expected to subtract about ¼ percentage point from potential growth each year. An easy way to help slow this trend would be to increase labor participation of underutilized groups—which in several Asian countries, including Japan and Korea, tend to be women.

If, over the coming 20 years, Japan raised its female labor participation rate from 62 percent to 70 percent—that of its Group of Seven industrial countries (G7) compatriots excluding outlier Italy—then its per capita GDP would be approximately 5 percent higher. Raising the female labor participation rate even further, say to that of northern Europe, could increase per capita GDP by an additional 5 percent. The first scenario could increase GDP growth in the transition years by about ¼ percentage point and the second, ½ percentage point. With medium-term potential GDP growth at about 1 percent, these increases translate into a 25 to 50 percent increase in Japan’s potential output in the transition years.

If Nakamura lived in Sweden, she would have the support she needed to “have it all,” and wouldn’t think twice about going back to her previous job after maternity leave. Making it easier for women like Nakamura to stay in the workforce will make it easier for Japan to remain a player in the global economy. Making the most of Asia’s women is an equitable progrowth strategy that makes good sense. ■

Chad Steinberg is a Senior Economist in the IMF’s Strategy, Policy, and Review Department and, until recently, was stationed in Tokyo at the IMF’s Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific.

This article is based on the author’s 2012 IMF Working Paper with Masato Nakane, “Can Women Save Japan?”