When Commodity Prices Surge

Finance & Development, December 2012, Vol. 49, No. 4

Gaston Gelos and Yulia Ustyugova

PDF version

![]() Commodity price swings

Commodity price swings

A price spike is likely to have more impact on countries with already high inflation levels and weak institutions

The recent surge in food prices means that many countries are soon likely to face a new round of inflation pressure. A severe drought in much of the United States and eastern Europe and problems in other food-producing countries have reduced crop yields. Prospects for continued deterioration in the supply mean prices are likely to stay high in the near term. Oil prices, too, have picked up, driven by geopolitical risks.

In the current global environment of uncertainty and slow economic growth, high and volatile commodity prices, as in 2008, pose a complex challenge. Policymakers must strive to keep the surge in commodity prices from triggering a sustained overall increase in inflation—that is, to prevent the commodity price shock from passing through to so-called core inflation (inflation stripped of volatile fuel and food prices).

This global environment not only causes policymakers to weigh the appropriate policy response, it also highlights the need to understand which policy frameworks (such as the type of monetary policy pursued and exchange rate approach taken) and structural characteristics—from labor markets to financial markets—help contain the inflationary effects of commodity price shocks. To date, there has been surprisingly little systematic research on this issue.

Myriad questions

Among the dimensions of the policy response to soaring commodity prices are such questions as these: Do countries with more independent central banks or those whose monetary policy targets a specific inflation rate experience lower pass-through of commodity price shocks to domestic inflation—including core inflation? What is the role of an economy’s openness to trade or the level of development of its financial sector in the transmission of international price shocks? How important is the preexisting level of inflation in determining pass-through? To what extent does a country’s governance framework—beyond the institutional features of the monetary regime—influence the impact on inflation? What role does exchange rate flexibility play?

To explore the role of these and other factors, we studied 31 advanced and 61 emerging market and developing economies, using several methodological approaches (Gelos and Ustyugova, 2012). To begin with, we examined how international commodity price swings affected domestic inflation rates across the countries during 2001–10 by estimating the pass-through from international commodity prices to domestic prices and relating them to country characteristics and policy frameworks (not, though, to any specific policy response). We did this using both country-by-country estimations and panel estimations (which use data from various countries simultaneously). We also analyzed the performance of headline (or overall) inflation and core inflation across the countries in the months surrounding the large 2008 commodity price increases, because the behavior of economic variables may be different when large shocks occur.

The findings confirm that commodity price shocks have stronger effects on domestic inflation in developing than in advanced economies. For example, in advanced economies, the median long-term pass-through to domestic inflation of a 10 percentage point food price shock was 0.2 percentage point. It was about four times larger in emerging market and developing economies. When it comes to fuel prices, the difference is less dramatic. But there is a much greater variance among developing countries in the size of the pass-through. This could reflect the use of price controls and subsidies in some of these countries.

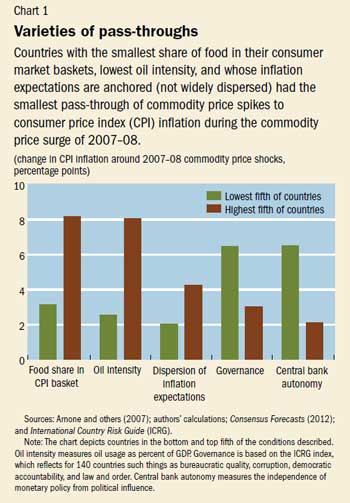

Not surprisingly, food shocks are more likely to have sustained inflationary aftereffects in countries with food as a sizable portion of the basket of goods and services measured by the consumer price index (CPI)—although the difference in pass-through is not fully explained by the different weights assigned to food in advanced and developing economies (see Chart 1). Similarly, fuel price shocks are passed through more in highly oil-intensive economies. According to our panel estimates, a 10 percentage point shock to international food prices, for example, is associated with a 1.4 percentage point increase in inflation in countries whose CPI food share is in the top fifth; the pass-through is only 0.3 percentage point for those with a food share in the bottom fifth.

Some surprises

What came as a surprise, however, is that some other country factors do not seem to affect the inflation response to commodity price shocks in the way economic theory predicts they should. For example, economic theory suggests that monetary policy is more effective in economies with more developed financial sectors and deeper financial markets. On the other hand, high financial dollarization (use of a foreign currency, often the dollar, in lieu of the domestic currency) is expected to limit the effectiveness of monetary policy, making it harder to ward off pass-through. However, we did not find evidence that either higher financial development or extensive dollarization significantly influenced the way international price shocks affected domestic inflation.

Neither could we document a statistically significant relationship between the pass-through of commodity price shocks to domestic inflation and labor market flexibility; economic theory predicts that economies whose firms can more easily adjust wages and their workforce will experience lower inflation pressure in response to such shocks. Nor can trade openness (measured by the share of exports and imports in total economic activity) generally be blamed for high pass-through of commodity price inflation to domestic prices. However, there is some indication that fuel price shocks have stronger effects on domestic inflation in more open developing economies.

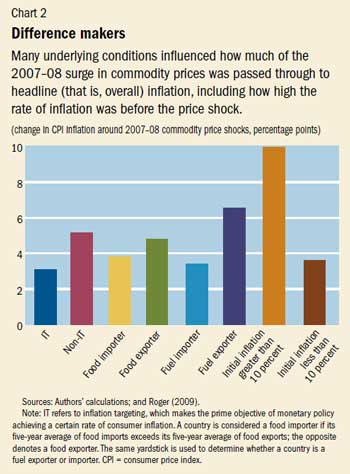

There is clear evidence that the higher the inflation rate before the shock, the higher the inflationary impact of a commodity shock. For example, after the 2008 shock, economies with initial inflation above 10 percent experienced, on average, a 6 percentage point higher rise in CPI inflation than countries with preexisting inflation below 10 percent (see Chart 2). Taylor (2000) suggests that the reason for this disparity is that the extent to which firms respond to increases in costs by raising their own prices depends on how persistent the increase is expected to be, and persistence is higher in high-inflation environments. Therefore, low and more stable inflation is associated with a lower inflationary impact of commodity price shocks (Choudhri and Hakura, 2006). There is also some indication that a larger dispersion of inflation expectations (a proxy for the degree of anchoring of inflation expectations) is associated with higher inflation pass-through. (For an early assessment of monetary policy around the 2008 shock, see Habermeier and others, 2009.)

Resisting price swings

What else can be done by policymakers to limit the sensitivity of domestic inflation to international commodity price swings? Our analysis suggests that better overall governance, greater central bank autonomy, and, to a lesser extent, the adoption of inflation-targeting frameworks seem to help anchor inflation expectations and reduce second-round effects of international commodity price shocks.

For example, countries with better governance frameworks as measured by the International Country Risk Guide found it easier to contain the inflationary impact of commodity price shocks over the period 2001–10. This result holds even when controlling for economies that target a CPI inflation rate. In response to a 10 percent increase in food price inflation, a country in the bottom fifth of the governance rating—which covers bureaucratic quality, corruption, democratic accountability, and law and order—on average experienced a 0.9 percentage point higher increase in inflation than a country in the top fifth. Similarly, countries with more autonomous central banks experienced less increase in CPI inflation at the time of the 2008 food price shock and had a smaller pass-through during 2001–10.

However, inflation targeting had a relatively modest impact on the pass-through from commodity price pressure during 2001–10. A 10 percentage point increase in international fuel price inflation, for example, was associated with a long-term inflationary impact on inflation targeters that was only 0.2 percentage point lower than on economies whose central banks do not target CPI inflation. Moreover, although there are indications that in 2008 inflation targeters were somewhat more able than other countries to prevent pass-through of the commodity price surge to general inflation (headline and core), the difference is not statistically significant.

It does appear that in the face of commodity price shocks, overall confidence in institutions is more important than whether a country formally declares itself an inflation targeter. ■

Gaston Gelos is an Advisor in the IMF’s Institute for Capacity Development, and Yulia Ustyugova is an Economist in the IMF’s Western Hemisphere Department.

References:

Arnone, Marco, Bernard J. Laurens, Jean-François Segalotto, and Martin Sommer, 2007, “Central Bank Autonomy: Lessons from Global Trends,” IMF Working Paper 07/88 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Choudhri, Ehsan U., and Dalia S. Hakura, 2006, “Exchange Rate Pass-Through to Domestic Prices: Does the Inflationary Environment Matter?” Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 25 (June), pp. 614–39.

Gelos, Gaston, and Yulia Ustyugova, 2012, “Inflation Responses to Commodity Price Shocks—How and Why Do Countries Differ?” IMF Working Paper 12/225 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Habermeier, Karl, and others, 2009, “Inflation Pressures and Monetary Policy Options in Emerging and Developing Countries: A Cross Regional Perspective,” IMF Working Paper 09/1 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2011, World Economic Outlook (Washington, September).

Roger, Scott, 2009, “Inflation Targeting at 20: Achievements and Challenges,” IMF Working Paper 09/236 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Taylor, John, 2000, “Low Inflation, Pass-Through, and the Pricing Power of Firms,” European Economic Review, Vol. 44, No. 7, pp. 1389–408.