A Big Question on Small States

Finance & Development, September 2013, Vol. 50, No. 3

Can they overcome their size-related vulnerabilities and grow faster and more consistently?

For every large country like China, India, and the United States, there is a small state like Suriname, Tuvalu, and Seychelles. And just as big states are a diverse lot, so are states with populations of less than 1.5 million.

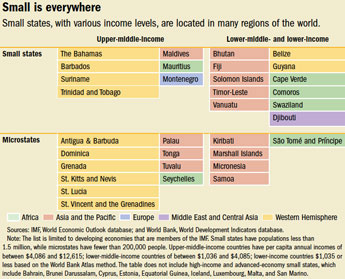

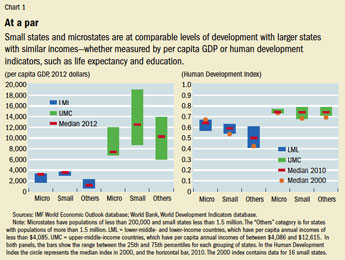

Some are rich. Some are poor. In fact, small states span the spectrum of income levels (see table). There are high-income fuel-exporting countries, such as Bahrain. There are also countries in the low-income group, such as Djibouti. Similarly, social indicators reflect a wide range of development. Some small states, such as Luxembourg, rank among the highest in the latest United Nations Human Development Index,  while others, such as Bhutan, rank among the lowest (see Chart 1).

while others, such as Bhutan, rank among the lowest (see Chart 1).

Most of the small states are islands or widely dispersed multi-island states; others are landlocked. Some are located far from major markets. The smallest of these, known as microstates, have populations below 200,000. About one-fifth of the IMF’s member countries are small states.

Small they may be. But the middle-income and lower-income small states we analyze here face complex problems. The Pacific island of Tuvalu, for example, with a land area of 10 square miles, is roughly one-seventh the size of Washington, D.C. That makes it difficult to grow crops.  Its neighbor, Kiribati, in contrast, has a population of 100,000 people spread over 3.5 million square kilometers of ocean—an area about the size of the Indian subcontinent. That makes for a country extraordinarily difficult to administer.

Its neighbor, Kiribati, in contrast, has a population of 100,000 people spread over 3.5 million square kilometers of ocean—an area about the size of the Indian subcontinent. That makes for a country extraordinarily difficult to administer.

Most Pacific island countries consist of hundreds of small islands scattered over an area in the Pacific Ocean that occupies 15 percent of the globe’s surface. This dispersion causes many problems, not the least of which is high trade costs. For example, the Pacific states of Samoa and Palau are about as far apart as the east coast of the United States and England.

A common problem

Small states have one common problem: they face constraints because of their size.

For starters, because they have tiny populations, the states cannot spread the fixed costs of government or business over a large number of people—that is, they cannot achieve economies of scale in the same way that larger states can. The result of these diseconomies of scale, as economists call them, is high costs in both the public and private sectors.

Their small size also seems to be reflected in a number of macroeconomic characteristics:

• Narrow production base: Although their economies are not uniform—some are commodity exporters, others are service based (mainly tourism or financial services)—all of them face problems establishing a competitive economic base. And where they do compete, it is typically in one or two goods or services, leaving them vulnerable to ups and downs in a handful of industries. Tourism accounts for more than half the foreign earnings for many of the Caribbean islands. Similarly, many small states in the Pacific depend on one product for most of their export earnings. In the Solomon Islands, for example, about half of export earnings come from logging.

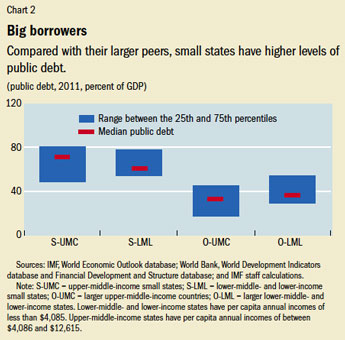

• Big government: Measured by the ratio of government expenditures to GDP, small states tend to have bigger governments than do larger states. This is partly a reflection of the diseconomies of scale that make the provision of public goods and services more costly than in larger states. In addition, a large share of expenditures is relatively inflexible—such as those directed to all-too-common natural disasters—or hard to reduce, such as the public wage bill. The high level of expenditure has often led to high levels of debt (see Chart 2).

• Poorly developed financial sector: About half of the small states have gained prominence as offshore financial centers. But financial institutions in offshore financial centers typically serve nonresidents. In general, the domestic financial sectors lack depth, are concentrated, and do not provide their citizens with adequate access to finance. The financial sectors are dominated by banks, whose high lending rates often hinder investment. Also, because the private sectors in small states are so tiny, commercial banks often end up financing the government—risking their soundness by becoming heavily exposed to one borrower. This has also complicated economic policy actions meant to lower the debt. In the highly indebted Caribbean countries, for example, commercial banks and nonbank financial institutions hold two-thirds of domestic public debt. In bigger countries, government debt is usually owned by a variety of individuals and by financial and nonfinancial institutions.

• Fixed exchange rates: Small states are more likely than larger ones to peg their exchange rates to another currency. Many of these small states are closely tied to a handful of larger economies that account for most of their export earnings. The peg eliminates exchange rate volatility, which helps smooth export earnings. At the same time, small states need to hold higher reserves than their larger brethren—not only to defend their currencies but also to insulate themselves from adverse outside events that can have a large negative effect on their well-being. Yet most have fewer reserves than considered optimal. The small states also have more limited ability to conduct monetary policy. Five of 13 small states in the Asia-Pacific region, for example, do not have a central bank.

• Trade openness: Small states are also more open to trade. Trade-to-GDP ratios are much larger in smaller economies than in larger ones with similar policies. Small states also seem to have somewhat lower trade barriers. A high degree of trade openness often leaves the small states vulnerable to shocks from terms of trade (the prices of exports compared with the prices of imports).

Small states face other common issues as well. Many are located in the open ocean, which makes them prone to natural disasters (such as earthquakes and hurricanes), and, because they are so small, typically the entire population and economy are affected by such disasters.

Natural disasters annually cost microstates in the Caribbean and the Pacific the equivalent of 3 to 5 percent of GDP. At the same time, many are islands that face particular challenges from climate change. Kiribati, for example, could be the first country to see its entire territory disappear under water as a result of global climate change that causes ice to melt at the polar caps, raising sea levels.

Moreover, the remoteness of many of these countries can be a problem because the paucity of arable land makes them dependent on imported foodstuffs, which can be very expensive.

Volatility reigns

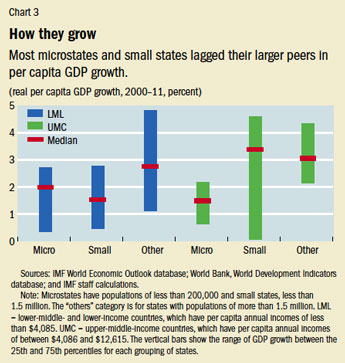

For the most part, small states have not shared in the improved economic growth of their larger peers since the late 1990s (see Chart 3). Large states have grown substantially faster in the 2000s than they did in the last two decades of the 20th century, outperforming smaller states. There are many reasons that explain why small states lag their larger peers—among them, a “brain drain,” as the best and brightest seek wider opportunities available in larger economies. The erosion of trade preferences in the exports of goods such as bananas and sugar also hold back small states.

But perhaps the most telling problem these states face is volatility. Small states have been plagued by highly erratic economic growth, which in the long run impedes growth, worsens income inequality, and increases poverty. During the 2000s, small states have had noticeably higher growth volatility than their larger counterparts—and lower growth rates. Their current accounts—mainly the difference between what the small states export and what they import—are considerably more volatile than those of larger states with similar income levels. This may reflect higher terms-of-trade volatility, which has a greater effect on small states because of their greater trade openness. In the fiscal sector, greater volatility is seen in both revenue and expenditures. Revenue volatility is typically linked to greater reliance on trade taxes, which wax and wane as trade rises and falls. Expenditure volatility is often associated with “lumpy” capital spending, spending responses to natural disasters, and a lack of discipline related to weak governing capacity.

Making the best of it

Small states can, however, compensate for their size-related problems by taking steps to exploit their advantages and offset their disadvantages. In general, these states should pursue the following:

• Sound economic policies: The best cure for volatility is prevention—through strong policies. For example, revenue volatility can be lessened by reducing dependence on trade taxes. Small states have begun to look at other sources of revenue, and many have successfully adopted value-added taxes. Their introduction in the microstates of the Caribbean has reshaped the revenue structure and eased revenue collection. Expenditure volatility can sometimes be reduced through public sector reforms that seek to improve governance and make fundamental structural reforms in the economy. Volatility in the external sector can be reduced by diversifying exports and trading partners. Although a tiny state, Samoa has successfully diversified its export products and markets—after a taro leaf blight in the 1990s showed the importance of reducing dependence on one crop.

In addition to reducing volatility, small states must foster stability. Steps to increase financial services should be paired with careful supervision by the appropriate legal and supervisory authorities to ensure financial stability. Given their greater exposure to external shocks, small states should accumulate adequate reserves or budget extra spending for potential disasters as well as explore insurance coverage.

• Regional integration and cooperation: One way to offset the size disadvantage is to create bigger markets through regional integration. Such initiatives are most advanced in the Caribbean. For example, the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union’s Regional Government Securities Market aims to integrate existing national securities markets into a single regional market, helping to exploit economies of scale in financial markets. Similarly, the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank uses a reserve account of contingency funds to assist member countries facing economic difficulties, including those caused by natural disasters.

• Involvement of the international community: Small states can also involve international institutions and development partners in identifying common solutions to regional problems. The World Bank, for example, has helped to set up a multicountry risk pool and an insurance instrument for damages caused by natural disasters. Similarly, the World Trade Organization’s Aid for Trade initiative has encouraged trade-related regional infrastructure. Internationally agreed debt-restructuring and -relief mechanisms, such as the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative and the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative, have helped some small states reduce their debt burden. Financial assistance is often crucial for small states. To weather natural disasters and other external shocks, small states have used a number of IMF financing instruments—including the Rapid Credit Facility, a type of emergency assistance. Perhaps most important, international institutions can provide technical assistance and training tailored to the needs of individual states.

Policies matter most

Size does create constraints, but effective policies can help small states overcome them. For example, Mauritius—a small, remote island state off the coast of eastern Africa—was deemed a strong candidate for failure by Nobel Prize–winning economist James Meade in the 1960s. It depended on one crop, sugar; was prone to terms-of-trade shocks; had high levels of unemployment; and lacked natural resources. But the country proved Meade wrong. It progressed to a well-diversified middle-income economy that earns revenues from tourism, finance, textiles, and advanced technology—as well as sugar. Whether measured by per capita income, human development indicators, or governance indicators, Mauritius is among the top African countries. The prudent policies Mauritius adopted fueled its transformation. For example, it attracted foreign direct investment to help spur its industries and built strong institutions to support growth.

Small states can, in fact, tackle their vulnerabilities. ■

Sarwat Jahan is an Economist, and Ke Wang is a Research Assistant, in the IMF’s Strategy, Policy, and Review Department.

This article draws from an IMF Board paper issued in 2013, “Macroeconomic Issues in Small States and Implications for Fund Engagement.” The paper had two supplements: “Asia and Pacific Small States—Raising Potential Growth and Enhancing Resilience to Shocks” and “Caribbean Small States—Challenges of High Debt and Low Growth.”