The Dollar Reigns Supreme, by Default

Finance & Development, March 2014, Vol. 51, No. 1

International currency arrangements have come under scrutiny in the aftermath of the global financial crisis

The dollar has been the preeminent global reserve currency for most of the past century. Its status as the dominant world currency was cemented by the perception of international investors, including foreign central banks, that U.S. financial markets are a safe haven. That perception has ostensibly driven a significant portion of U.S. capital inflows, which have surged in the past two decades. Many believe that this dollar dominance has allowed the United States to live beyond its means, running sizable current account deficits financed by borrowing from the rest of the world at cheap interest rates. Some other countries have chafed at this “exorbitant privilege” enjoyed by the United States.

Moreover, the fact that a rich country like the United States has been a net importer of capital from middle-income countries like China has come to be seen as a prime example of global current account imbalances. Such uphill flows of capital—contrary to the prediction of standard economic models that capital should flow from richer to poorer countries—have led to calls for a restructuring of global finance and a reconsideration of the roles and relative importance of various reserve currencies.

The 2008–09 global financial crisis, whose aftershocks continue to reverberate through the world economy, led to heightened speculation about the dollar’s looming, if not imminent, displacement as the world’s leading currency.

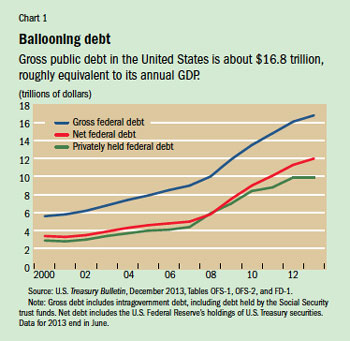

Indeed there are indications that the dollar’s status should be in peril. The United States is beset by a high and rising level of public debt. Gross public (federal government) debt has risen to $16.8 trillion (see Chart 1), roughly equal to the nation’s annual output of goods and services. The aggressive use of unconventional monetary policies by the Federal Reserve, the U.S. central bank, has increased the supply of dollars and created risks in the financial system. Moreover, political gridlock has made U.S. policymaking ineffectual and, in some cases, counterproductive in driving the economic recovery. There are also serious concerns that recent fiscal tightening has constrained the government’s ability to undertake expenditures on items such as education and infrastructure that matter for long-term productivity growth.

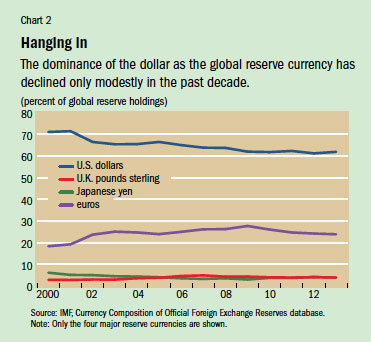

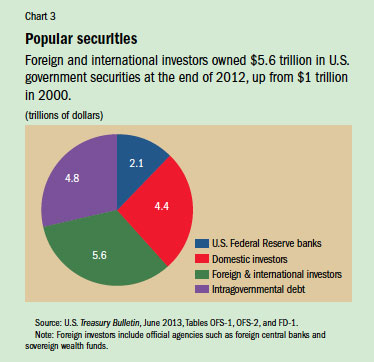

All these factors should have set off an economic decline in the United States and hastened erosion of the dollar’s importance. But the reality is starkly different. The dominance of the dollar as a global reserve currency has been barely affected by the global financial crisis. Not only did the dollar’s share in global foreign currency reserves change only modestly in the decade before the crisis, it has held steady at about 62 percent since the crisis began (see Chart 2). Overall, foreigners have sharply increased their holdings of U.S. financial assets. Foreign investors now hold nearly $5.6 trillion in U.S. government securities (see Chart 3), up from $1 trillion in 2000. In fact, during and after the recent crisis (since the end of 2006), foreign investors purchased $3.5 trillion in Treasury securities. Even as the stock of U.S. federal debt has been rising, foreign investors have steadily increased their share of the portion of that debt that is “privately held” (not held by other parts of the U.S. government or the Federal Reserve). That share now stands at 56 percent. In some respects, then, the dollar’s role as the dominant reserve currency has strengthened since the crisis.

How did this happen against all logic? Is the situation tenable?

The rush to safety

One of the striking changes in the global economy over the past decade and a half is the rising importance of emerging market economies. These economies, led by China and India, have accounted for a substantial fraction of global GDP growth over this period. Interestingly, the crisis did not deter these countries from allowing freer movement of financial capital across their borders. While this might seem risky, emerging markets have been able to alter the makeup of their external liabilities from debt to safer and more stable forms of capital inflows, such as foreign direct investment. Still, even as their vulnerability to currency crises has declined, these economies face new dangers from rising capital inflows, including higher inflation and asset market booms and busts.

The global financial crisis shattered conventional views about the amount of reserves an economy needs to protect itself from the spillover effects of global crises. Even countries with large stockpiles found that their reserves shrank rapidly over a short period during the crisis as they sought to protect their currencies from collapse. Thirteen economies that I studied lost between a quarter and a third of their reserve stocks over about eight months during the worst of the crisis.

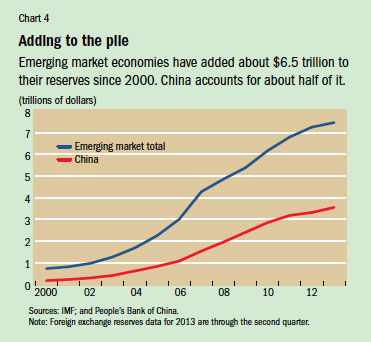

Rising financial openness and exposure to capital flow volatility have increased official demand for safe financial assets—investments that at least protect investors’ principal and are relatively liquid (that is, easy to trade). Emerging market economies have a stronger incentive than ever to accumulate massive war chests of foreign exchange reserves to insulate themselves from the consequences of volatile capital flows. In fact, since 2000, emerging markets have added about $6.5 trillion to their reserve stockpiles, with China accounting for about half of this increase (see Chart 4).

In addition, many of these countries, as well as some advanced economies such as Japan and Switzerland, have been intervening heavily in foreign exchange markets—buying foreign currencies to limit appreciation of their own currencies, thereby protecting their export competitiveness. Exchange market intervention also results in accumulation of reserves, which must be parked in safe and liquid assets, generally government bonds. This kind of intervention has led to rising demand for safe assets.

Regulatory reforms that require financial institutions to hold safe and liquid assets as a buffer against adverse financial shocks are adding to this demand. Moreover, at times of global financial turmoil, private investors worldwide also clamor for such assets.

This has led to an imbalance: the supply of safe assets has fallen, even as the demand for them has surged. The crisis dealt a blow to the notion that private sector securities, even those issued by rock-solid corporations and financial institutions, can be considered safe assets. At the same time, government bonds of many major economies—such as those in the euro area, Japan, and the United Kingdom—also look shakier in the aftermath of the crisis as those economies contend with weak growth prospects and sharply rising debt burdens. With its deep financial markets and rising public debt, the U.S. government has thus solidified its status as the primary global provider of safe assets.

Paradoxes

Does it make sense for other countries to buy more and more U.S. public debt and regard it as safe when that debt is ballooning rapidly and could threaten U.S. fiscal solvency? The high share of foreign ownership makes it tempting for the United States to cut its debt obligations simply by printing more dollars, which would reduce the real (that is, after-inflation) value of that debt—implicitly reneging on part of its obligation to those foreign investors. Of course, such an action, while tempting, is ultimately unappealing, because it would fuel inflation and affect U.S. investors and the U.S. economy as well.

In fact, there is a delicate domestic political equilibrium that makes it rational for foreign investors to retain faith that the United States will not inflate away the value of their holdings of Treasury debt. Domestic holders of U.S. debt include retirees, pension funds, financial institutions, and insurance companies. These groups constitute a powerful political constituency that would inflict a huge political cost on the incumbent government if inflation were to rise sharply. This gives foreign investors some reassurance that the value of their U.S. investments will be protected.

Still, emerging market countries are frustrated that they have no place other than dollar assets to park most of their reserves, especially since interest rates on Treasury securities have remained low for an extended period, barely keeping up with inflation. This frustration is heightened by the disconcerting prospect that, despite its strength as the dominant reserve currency, the dollar is likely to fall in value over the long term. China and other key emerging markets are expected to continue registering higher productivity growth than the United States, so once global financial markets settle down, the dollar is likely to return to the gradual depreciation it has experienced since the early 2000s. In other words, foreign investors stand to get a smaller payout in terms of their domestic currencies when they eventually sell their dollar investments. Thus, foreign investors seem willing to pay a high price—investing in low-yielding U.S. Treasury securities rather than higher-return investments—to hold these assets that are otherwise seen as safe and liquid.

Competitors

There are tangible and intangible benefits to a country whose currency serves as a reserve currency. In addition to the prestige conferred by this status, it also means access to cheap financing in the country’s domestic currency and the benefit of seigniorage revenue—the difference between the purchasing power of money and the cost of producing it—which can be extracted from both domestic and foreign holders of the currency.

Other major advanced economies either have much smaller financial markets or, as in the case of Europe and Japan, have relatively weak long-term growth prospects and already high levels of public debt. As a result these currencies are unlikely to return to their former glory anytime soon. But because of the benefits that have accrued to the dollar from its reserve currency status, there should, in principle, be new competitors seeking a share of those benefits.

One putative competitor to the dollar, which has been the subject of considerable attention, is the Chinese renminbi. China’s economy is the second biggest in the world and is on track to become the largest over the next decade. The Chinese government is taking many steps to promote the use of the renminbi in international financial and trade transactions. These steps are fast gaining traction given the economy’s sheer size and prowess in international trade. As restrictions on cross-border capital mobility are removed and the currency becomes freely convertible, the renminbi will also become a viable reserve currency.

However, the limited financial market development and structure of political and legal institutions in China make it unlikely that the renminbi will become a major reserve asset that foreign investors, including other central banks, turn to for safekeeping of their funds. At best, the renminbi will erode but not significantly challenge the dollar’s preeminent status. No other emerging market economies are in a position to have their currencies ascend to reserve status, let alone challenge the dollar.

Of course, the dollar’s dominance as a store of value does not necessarily translate to continued dominance in other aspects. The dollar’s roles as a medium of exchange and unit of account are likely to erode over time. Financial market and technological developments that make it easier to conduct cross-border financial transactions using other currencies are reducing the need for the dollar. China has signed bilateral agreements with a number of its major trading partners to settle trade transactions in their own currencies. Similarly, there is no good reason why contracts for certain commodities, such as oil, should continue to be denominated and settled only in dollars.

By contrast, because financial assets denominated in U.S. dollars, especially U.S. government securities, remain the preferred destination for investors interested in the safekeeping of their investments, the dollar’s position as the predominant store of value in the world is secure for the foreseeable future.

What lies ahead

Official and private investors around the world have become dependent on financial assets denominated in U.S. dollars, especially because there are no alternatives that offer the scale and depth of U.S. financial markets. U.S. Treasury securities, representing borrowing by the U.S. government, are still seen as the safest financial assets in global markets. Now that foreign investors, including foreign central banks, have accumulated enormous investments in these securities as well as other dollar assets, they have a strong incentive to keep the value of the dollar from crashing. Moreover, there are no alternative currencies or investments that provide a similar degree of safety and liquidity in the quantities demanded by investors. Therein lies the genesis of the “dollar trap.”

The reason the United States appears so special in global finance is not just because of the size of its economy, but also because of its institutions—democratic government, public institutions, financial markets, and legal framework—which, for all their flaws, still set the standard for the world. For instance, despite the Federal Reserve’s aggressive and protracted use of unconventional monetary policies, investors worldwide still seem to trust that the Fed will not allow inflation to get out of hand and diminish the value of the dollar.

Ultimately, getting away from the dollar trap will require significant financial and institutional reforms in countries that aspire to have their currencies erode the dollar’s dominance. And it will take major reforms to global governance to reduce official demand for safe assets by providing better financial safety nets for countries. Such reforms would eliminate the need for accumulation of foreign exchange reserves as self-insurance against currency and financial crises.

The dollar will remain the dominant reserve currency for a long time, mainly for want of better alternatives. ■

Eswar Prasad is a professor in the Dyson School at Cornell University, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, and a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research.

This article draws on the author’s new book, The Dollar Trap: How the U.S. Dollar Tightened Its Grip on Global Finance.