Sharing the Wealth

Finance & Development, December 2014, Vol. 51, No. 4

Sanjeev Gupta, Alex Segura-Ubiergo, and Enrique Flores

Countries that enjoy a resource windfall should be prudent about distributing it all directly to their people

Angola is the second largest oil producer in sub-Saharan Africa and one of the continent’s richest countries. Yet more children under the age of five die there than in most places in the world.

Most resource-rich countries lack the types of institutions needed to manage natural resource wealth effectively, and past performance does not bode well for countries with a resource windfall. Many of their citizens face continued poverty with little prospect of a significant improvement in living conditions. Angola’s under-five infant mortality rate is a vivid example.

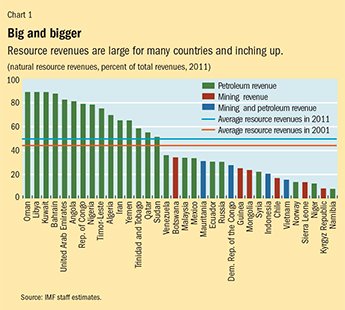

In recent years, high commodity prices and new natural resource discoveries have increased many countries’ resource revenues, both as a share of the budget and in percent of GDP, offering new prospects for raising the population’s standard of living (see Chart 1). But few countries stand out as good examples of effective resource wealth management. Botswana, Chile, Norway, and the U.S. state of Alaska are some exceptions.

The experience of the success stories suggests that natural resource wealth management requires a commitment to three interrelated principles: fiscal transparency, a rules-based fiscal policy, and strong institutions for public financial management. For example, Norway and Alaska are models of transparency in the way they collect and budget natural resource revenue. This transparency helps people understand the use of resource wealth and holds political leaders accountable for their decisions. Chile’s fiscal rules protect resource wealth from the vagaries of political pressure, and its strong institutions are able to manage public investment. This helps transform natural resource wealth into productive assets, including infrastructure and human capital.

Some suggest that governments should give up their resource revenue and distribute it directly to the population. There are some good arguments to support this view—and strong arguments against it. Direct distribution is not a silver bullet (Gupta, Segura-Ubiergo, and Flores, 2014).

Devil’s excrement

The weak track record of most resource-rich countries’ use of natural resource revenue supports the view that new discoveries could be as much a curse as a blessing. Why does this happen?

A resource boom can cause a currency’s real exchange rate to appreciate, which reduces the competitiveness of the country’s exports and diverts resources toward sectors of the economy that don't engage in foreign trade—what is widely known as Dutch disease. Moreover, analysts have found that resource wealth is often associated with government corruption that undermines democratic accountability. These arguments are often used to suggest that natural wealth can become a “resource curse.” This idea was captured vividly by Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonso, Venezuela’s former minister of mines and hydrocarbons and cofounder of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, who described petroleum as the “devil’s excrement” and warned of its potential to spawn waste, corruption, excessive consumption, and debt.

Many resource-rich countries lack both robust public finance management systems to ensure the transparency and efficiency of their budget process and the checks and balances in the decision-making process that are needed to ensure an effective use of resource wealth. Without them, they have struggled to follow the positive example of countries like Botswana, Chile, and Norway.

Building strong, stable institutions takes time. In the meantime, some scholars suggest, countries should distribute their resource revenues directly to the population, to boost economic growth and improve living standards (see “Spend or Send” in the December 2012 F&D).

Various arguments support this view, chiefly the claim that distribution prevents the government from misusing resource revenues and increasing its size. Some resource-rich countries arguably would welcome some form of direct distribution of revenue, but in others it could constrain the optimal provision of public goods. Moreover, even if the goal is to limit the size of the government by limiting access to resource revenue, alternatives such as reducing taxes are probably more efficient.

Another argument focuses on the impact of taxation on accountability (Sandbu, 2006). If resource revenues were distributed to the population and taxed to finance a portion of public goods, citizens would demand greater accountability in public spending programs. But this assumes that the gains from greater government accountability outweigh the efficiency losses associated with transferring revenues to the population and then taking some back. It also does not take into account that the transfer mechanism may be afflicted by the same institutional weaknesses and corruption as those of a typical resource-rich country.

How much and to whom

Direct distribution is a way to transfer some or all resource revenue to citizens to reduce the government’s discretionary authority over such resources and foster greater accountability. Discretionary authority and accountability are linked because citizens are less inclined to demand accountability if politicians can choose who is to receive resource revenues.

Views differ on how much of the revenues to distribute. One extreme calls for passing all natural resource revenues on to citizens, while more moderate proposals—Birdsall and Subramanian (2004) proposed for the case of Iraq distributing at least half—suggest returning only a portion of revenue or even just part of the investment income from a natural resource fund. The debate over how much to distribute centers around the economic consequences of such distribution, including the impact on work incentives, household savings, and overall macroeconomic stability.

As for who should receive resource revenues, distributing resources to all citizens has the appeal of eliminating political discretion over which groups should benefit. But universal transfers can have unintended consequences—such as encouraging families to have more children, which can be avoided by limiting transfers to adults. Some argue for pursuing social goals by targeting the poorest segments of the population or imposing conditions such as children’s school attendance. These laudable goals could help galvanize support for such mechanisms. They could, however, also lead to tension between reducing the coverage by targeting a particular segment of the population—particularly the poor, whose political voice is usually weaker—and increasing accountability. Moreover, the poor are not well equipped to handle income volatility, which these mechanisms would need to address.

Some argue for direct distribution outside the budget, which is subject to government corruption. This proposal would set aside resource revenue from the budgetary accounts and subject it to scrutiny, perhaps by an independent body rather than the parliament. Collection and distribution could even fall to an institution other than the national tax agency. Proponents of this idea contend that a separate mechanism to distribute resource revenues is more credible in the eyes of the population. But however achieved, direct distribution is not a recipe for eliminating corruption. It is naive to assume that a corrupt government would agree to direct distribution to deal with the problem. And there is no guarantee that the mechanism for distribution would not suffer from similar corruption.

Speaking from experience

Alaska has implemented the best known and perhaps most successful example of a direct distribution mechanism. But it is a conservative model with a relatively small dividend amounting to only 3 to 6 percent of Alaskans’ per capita income. Just a share of Alaska’s oil revenue goes into the fund, and only the investment income from this fund is distributed—subject to a cap of 5 percent of the fund’s total market value. The fund is managed by the Alaska Department of Revenue, and strong checks and balances within the budget make it in many ways a model of transparency. The case is widely viewed as a success, but one that was clearly achieved from a position of institutional strength and transparency, not as a solution to an institutional problem.

Given the limited number of direct distribution mechanisms worldwide, a look at related policies offers insight into what does and doesn’t work. It is always risky to make inferences from related policies, but the following cases provide some lessons:

• Venezuela has established a series of social programs called misiones. One focuses on adult literacy and remedial high school classes for dropouts; another on universal primary health care; and yet others on the construction of new houses for the poor, retirement benefits for the poor, food at discounted prices, and scholarships for graduate studies. As highlighted by Rodrίguez, Morales, and Monaldi (2012), these programs are funded directly by the state oil company and are therefore run outside the budget. As such, they give increased discretionary authority to the government. Some studies suggest that these programs suffer from as much corruption and populist pressure as the budget itself—which calls into question whether direct mechanisms outside the budget circumvent corruption.

• Experience with income support programs in advanced economies highlights the plausible negative impact of direct distribution transfers on the labor supply. These programs are meant to provide basic support to households that have little or no earnings. Some of this income support is then taxed away. Such programs have been criticized for providing insufficient incentives to low-income earners to work; earned income credit programs for which only workers are eligible are one alternative.

• The conditional cash transfer programs now popular in many developing economies can also dampen the incentive to work. These programs seek to reduce poverty by providing support—in the form of a cash transfer—subject to certain conditions, such as enrolling children in school or receiving vaccinations. The objective is to break the cycle of poverty by helping the current generation while promoting investment in the future generation. Most studies have found that the impact on the labor supply is negligible if the transfer is small and the benefits are targeted to the poorest households. Programs with larger transfers and with broader coverage—including better-off segments of the population—reduce labor participation more.

• Large energy subsidies in oil-rich countries are popular because the population expects to reap benefits from the abundance of oil resources. Pretax subsidies that allow firms and households to pay less than prevailing international prices are about 8½ percent of GDP in the Middle East and North Africa region. These generalized subsidies lead to inefficient resource allocation—which hurts growth—and disproportionately benefit those who are better off, which only worsens income inequality. Despite these drawbacks, the public supports subsidies because it sees no other way of benefiting from the abundance of natural resources.

• Worker remittances—money sent home by people working abroad—place additional resources in the hands of the household sector, as do direct distribution mechanisms. Experience suggests that most remittances are used for current consumption, and their impact on long-term growth is inconclusive. This casts doubt on the claim that direct distribution does not exacerbate Dutch-disease effects because the private sector will save when it receives a windfall just as the government does.

Lessons learned

Several lessons emerge from the Alaskan experience and that of related policies.

First, the overall design of fiscal policies could include direct distribution mechanisms, starting small to limit the impact on the labor supply. Limiting the proportion of resources directly distributed would ensure enough is available to the government for the provision of critical public services, as well as to ameliorate the impact of Dutch disease—as stressed by Hjort (2006).

Second, direct distribution is just as subject to corruption as public programs, so it should not be established outside the budget.

And, finally, it is important to remember that direct distribution of resource revenues doesn’t safeguard the needs of future generations.

Before embarking on direct distribution of resource revenues, a country must prepare its fiscal framework by

• determining the level of public revenue and spending necessary to ensure domestic macroeconomic stability and sustainable external balances;

• adopting policies that mitigate the impact of volatile commodity prices on revenue;

• accounting for uncertainty in the level of natural resource production and how much revenue the economy can absorb; and

• saving resources for future generations.

Direct distribution does not obviate the need to address these issues head-on. Although some argue that shifting the burden of managing volatility to the private sector could lead to improved outcomes, there is little evidence to support such a claim. As noted earlier, evidence from remittance-receiving countries suggests that the bulk of the money received is used for consumption rather than saving. While public sector management of volatility in resource-rich countries has been far from stellar, an IMF study (2012) shows that it seems to have improved as these countries shifted from policies that reinforced changes in commodity prices between 1970 and 1999 to broadly neutral ones in the past decade.

Direct distribution can have a significant impact on income distribution. In Ghana, for example, resource revenues amount to about 5 percent of GDP. The poorest 10 percent of the population earns only 2 percent of GDP, so universal direct distribution would raise the income of that group by about 25 percent. But the distribution of resource revenues would reduce the budgetary resources available for the provision of public services, which could in turn have adverse consequences on income distribution.

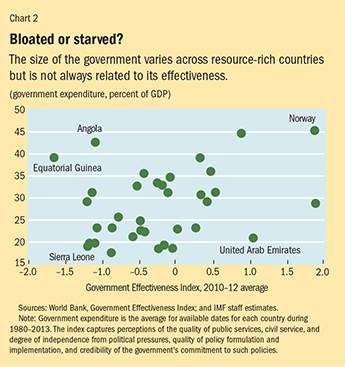

Another effect of direct distribution would undoubtedly be smaller government. Shifting resources to the private sector could curtail wasteful spending in some resource-rich countries but in others it could lower public spending to the point of threatening necessary infrastructure and public goods. Total expenditure in resource-rich countries averages about 28 percent of GDP, which seems broadly in line with that in non-resource-rich economies. But there are significant differences in government size and institutional capacity across resource-rich countries (see Chart 2). The likely impact on income distribution and provision of public services only reinforces the need to start small when it comes to direct distribution.

Worth pursuing?

While the view that direct distribution leads to increased accountability is appealing, large-scale direct distribution has not been tested anywhere in the world. There is little evidence that the extreme of distributing all resource revenues to the population is effective, but a case for modest direct distribution similar to the Alaskan model could be considered.

Even judicious distribution must be implemented under an appropriate fiscal framework and on a small scale to reduce the very plausible risk that distribution will stifle the provision of critical public services, lead to a drop in labor participation, or strain the government’s administrative capacity. ■

Sanjeev Gupta is a Deputy Director and Enrique Flores is a Senior Economist, both in the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department, and Alex Segura-Ubiergo is the IMF’s Resident Representative in Mozambique.

References

Birdsall, Nancy, and Arvind Subramanian, 2004, “Saving Iraq from Its Oil,” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 83, No. 4, pp. 77–89.

Gupta, Sanjev, Alex Segura-Ubiergo, and Enrique Flores, 2014, “Direct Distribution of Resource Revenues: Worth Considering?” IMF Staff Discussion Note 12/08 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Hjort, Jonas, 2006, “Citizen Funds and Dutch Disease in Developing Countries,” Resources Policy, Vol. 31, No. 3, pp. 183–91.

International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2012, “Macroeconomic Policy Frameworks for Resource-Rich Developing Countries” (Washington).

Rodrίguez, Pedro L., José R. Morales, and Francisco J. Monaldi, 2012, “Direct Distribution of Oil Revenues in Venezuela: A Viable Alternative?” Center for Global Development Working Paper 306 (Washington).

Sandbu, Martin E., 2006, “Natural Wealth Accounts: A Proposal for Alleviating the Natural Resource Curse,” World Development, Vol. 34, No. 7, pp. 1153–170.