Point of View

No Worker Left Behind

Finance & Development, December 2016, Vol. 53, No. 4

The right policy mix means good jobs at home and abroad

Britain’s vote to exit the European Union has been widely interpreted as a retreat from globalization. The old political consensus that globalization is good for everyone is undeniably under pressure, with the Brexit result one expression of that. And while the debate in the run-up to the referendum centered on the movement of people through migration, the result brought into focus broader questions about the other two pillars of globalization—movement of goods and money across international borders. Areas of the United Kingdom in which manufacturing jobs have disappeared over the past 30 years overwhelmingly voted to leave the European Union; outside the more prosperous London and the southeast, fewer than one in seven local areas voted to remain.

Across the Atlantic, the impact of international trade on jobs and pay was an important part of the U.S. presidential election debate. So while some puzzle over the rise of anti-globalization, the more relevant question is why there has been relatively little debate about its winners and losers, and whether globalization can be reshaped to deliver for ordinary people.

Trade unionists have an important voice in these debates. We’re instinctive internationalists, with a long tradition of supporting fair trading arrangements and multi-national cooperation. Our values also tell us to assess the strength of any idea, policy, or trend on the basis of its impact on working people’s jobs, pay, and rights.

Assessing globalization first requires us to define it. One feature of the global economy over the past 30 years has been the significant increase in global trade volumes, with 1988–2008 seen as a “heyday of global trade integration,” fueled by the end of the Cold War, the entry of China into global markets, and the reduction of trade barriers around the world (Corlett, 2016).

But not only did the cross-border volume of trade in goods and services increase over that period, there was also a significant increase in the cross-border movement of capital. Many countries reduced or ended controls on capital inflows and outflows in the belief that this would help drive economic growth. So while the increase in the volume of global trade has been seen by many as inevitable—at least after China entered world markets—the increase of financial flows around the world was a clear policy choice.

How have working people fared following this significantly increased movement of goods and money? The period has coincided with an improvement in living conditions for many in poorer countries. Rapid economic growth in China, the most populous country in the world, helped cut the number of people living on less than $1.90 a day by more than a billion between 1981 and 2012. And, as economist Branko Milanović has shown, people in many poor countries have seen significant income gains.

Although it is laudable that absolute poverty has been relieved, as trade unionists, our objectives also include the pursuit of greater equality. And on that score, while inequality between countries has been reduced, within countries across the globe it has soared.

For example, although the United Kingdom now sees record employment rates, high rates of unemployment—averaging 11 percent between 1980 and 1988—left deep scars in terms of poor health and weak job prospects in many communities affected by the loss of manufacturing jobs. In 1980, jobs in manufacturing made up one in four workforce jobs; now it is fewer than one in ten (ONS, 2016).

Many manufacturing workers, including those in the U.K. steel industry, are still suffering from global competition. While increased exposure to Chinese markets has lowered the price of consumer goods in the United Kingdom, workers in industries in competition with China have suffered from longer spells of unemployment and lower pay, with the lowest-paid workers suffering most (Pessoa, 2016).

Working people’s pay in the United Kingdom has been held back over time by a shift away from higher-skill and higher-paying jobs, including in manufacturing, to lower-paying jobs in the service sector. But in recent years, it’s been the impact of the financial crisis that has taken center stage, with the United Kingdom experiencing the largest fall in real average wages of any Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development country except Greece. As suggested in “Neoliberalism: Oversold?” in the June 2016 issue of F&D, the claims that financial openness would lead to more stable growth appear to have been significantly overstated, with capital account liberalization leading to both increased economic volatility and inequality. The run-up to the financial crisis saw an unsustainable increase in private debt, not only in the United States, but also in smaller countries such as the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Spain, and an increasingly integrated financial system helped ensure that when the crisis came, it spread rapidly around the world.

But viewing the downgrade in workers’ jobs and pay over the past 30 years as solely the result of globalization risks letting national governments off the hook. Domestic politicians have often given the impression that they are powerless in the face of global trends. But their policy choices have made a huge difference to the prospects for working people’s jobs and pay.

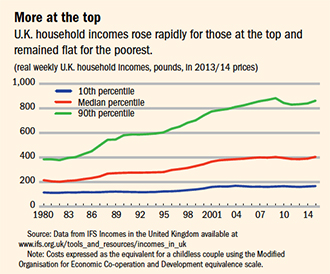

Inequality in the United Kingdom grew rapidly in the 1980s (see chart), with sharp rises in incomes for those at the top, slower median income growth, and flat-lining for those at the bottom. Globalized trade and finance played a part, but widening earnings differentials were exacerbated in the 1980s by a series of tax and benefit changes. Redistributive action in the 2000s helped prevent the gap from widening further but was not enough to close it.

Most important for trade unions, attacks on collective bargaining rights progressively weakened one of the most important protections against inequality. Countries with a higher coverage of collective bargaining agreements enjoy lower wage inequality, including between high- and low-skilled workers, between women and men, and between workers on regular and temporary contracts (ILO, 2016).

So our first role as trade unionists in debates about globalization is to remind our own governments that they have the power to improve working people’s lives. That means encouraging the investment needed to bring back the high-quality jobs that have disappeared, and enabling and encouraging trade unions to continue their vital work in protecting rights and pay. To the extent that wages are converging globally, there are new opportunities for unions to combine across borders and ensure the gains are shared more fairly, as well as to speak out whenever and wherever we see unfair treatment of workers.

At the international level, we need to judge each proposal—whether for greater openness on trade or for greater cooperation on taxation—based on its likely impact on working people’s jobs, rights, and living standards. We at the Trades Union Congress have strongly opposed the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) on the grounds of its likely adverse impact on the equitable distribution of the gains of increased trade, on the public services on which many working people depend, and on the policy space for democratically elected governments to regulate for consumer, environmental, and workplace protections. But we still maintain that retaining the social dimension and access to the openness of the EU single market remains the best way for good British jobs to be supported once we leave the European Union.

Our insistence that things can be different needs to extend to the international level too. The welcome re-examination of capital account liberalization and fiscal consolidation has brought into focus the question of how global finance can better support the productive economy, and the desirability of an international approach that allows space for governments to pursue this within their own country. Many have seen the reforms of the Bretton Woods era after World War II as aiming at that goal, during a period when working people saw significant gains in their living standards. The trade unions played an active role in developing that consensus; our aim is to once again play a role in developing a globalization that works for working people. ■

References

Corlett, Adam, 2016, “Examining an Elephant” (London: Resolution Foundation).

International Labour Organisation (ILO), 2016, “If You Want to Tackle Inequality, Shore Up Collective Bargaining,” blog, March 3.

Office for National Statistics, Labour Market Statistics, September 2016.

Pessoa, João Paulo, 2016, “International Competition and Labor Market Adjustment,” Centre for Economic EP Discussion Paper 1411 (London).

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.