Playing Catch-up

Finance & Development, June 2017, Vol. 54, No. 2

Lisa Dettling and Joanne W. Hsu

Youth today are not building wealth the way their parents did

Millennials began to enter the workforce during the most severe global economic crisis since the Great Depression, and their present and future economic decisions will be shaped by the historic upheaval in housing, financial, and labor markets they faced at the onset of adulthood. Millennials must also contend with other emerging issues critical to their prospects of building wealth, such as the rapidly escalating cost of higher education and uncertain retirement income.

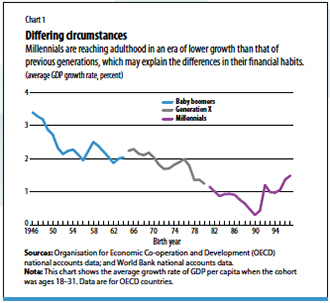

These developments have presented millennials with economic circumstances very different from those of preceding generations. We highlight three generations of young adults and the early years of their adulthood: baby boomers (born between 1946 and 1964), Generation X (born between 1965 and 1980), and millennials (born after 1980) (see Chart 1). Successive cohorts born between 1946 and 1990 generally experienced slower economic growth during young adulthood than those that came before them. These macroeconomic conditions were the result of world developments that differed across generations: the post–World War II recovery, the end of the Cold War, the rise of computing and the Internet, and the Great Recession, among many others. On average, young adult baby boomers faced considerably more robust economic growth than both Generation X and millennial young adults; millennials (thus far) have experienced the worst economic circumstances as they entered adulthood.

To see how these broad patterns of macroeconomic growth affected the financial situation of the typical household in these different cohorts, we turn to the 1983 to 2013 waves of the Survey of Consumer Finances, a nationally representative survey of household wealth in the United States conducted by the Federal Reserve Board.

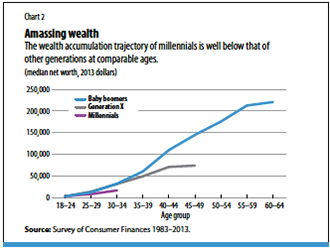

To capture families’ general financial situations over their life cycle, we focus on median net worth—a general measure of a family’s net economic position, defined as the difference between its assets and liabilities. Though millennials are just starting to accumulate wealth, their current trajectory is well below that of both the baby boomer and Generation X cohorts at comparable ages (see Chart 2). Between ages 25 and 34, the typical millennial’s net worth was about 60 percent that of the typical baby boomer at the same age. And although baby boomers and Gen Xers looked similar in young adulthood, Gen Xers are currently faring worse than their baby boomer counterparts at the same age, due in part to the Great Recession.

Just as the economic circumstances of young adults vary across generations, so too do the primary challenges and opportunities for building wealth. In this article, we will home in on three particular issues that affect how the millennial generation builds wealth: the growing cost of higher education, declines in home ownership, and changes in how families save for retirement. These three factors represent some of the largest components of household wealth, and their context has changed dramatically across generations.

Borrowing for education: The cost of attending college in the United States has far outstripped the pace of inflation in the past few decades. But the economic returns of a college degree remain high, and millennials are the most educated generation. To finance the rising cost of obtaining a college education, young adults are increasingly taking out student loans. In 1985 there were 8.9 million total student loan borrowers, which had increased nearly fivefold by 2014, to 42.8 million. And the average borrower is taking on more debt than ever: aggregate student loan volume in the United States had grown from $64 million in 1985 to $1.1 trillion by 2014 (in 2013 dollars; Looney and Yannelis 2015).

As a result, millennials entered their working lives with much larger debt than young adults of previous generations. These debt burdens may continue to influence their choices and economic circumstances for years to come.

Home ownership: Owning a home is a key way for families to accumulate wealth because it acts as a forced saving mechanism and allows owners to realize price gains over time. Homes are most families’ largest asset, and movements in housing wealth have been shown to be positively correlated with consumption and childbearing.

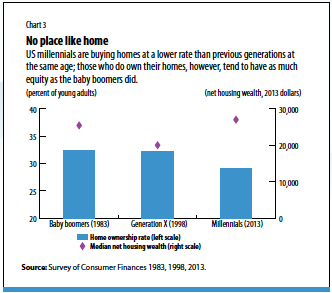

However, young adults in the United Kingdom, the United States, and Europe have experienced declining home ownership rates. Millennial home ownership rates are nearly 3 percentage points, or 10 percent, lower than those of their baby boomer and Generation X counterparts at the same age (see Chart 3). For millennials who have purchased a home, however, net housing wealth (the value of the home, minus mortgage debt) is about the same as that of their baby boomer parents at the same age.

Living with Mom and Dad

Furthermore, there is growing evidence that, rather than renting, a growing number of young adults in Europe and the United States are choosing to live with their parents into young adulthood and are not forming independent households. In the United States, the number of millennials living with their parents rose by about 12 percent during the Great Recession.

It remains to be seen if millennials are delaying home purchases or forgoing home ownership altogether. New research suggests barriers to financing a home, such as borrowing constraints, are at least partially to blame for falling home ownership rates and rising coresidence rates (Martins and Villanueva 2009; Dettling and Hsu 2014). Whether these barriers will ease in the future is unknown. However, a recent study in the United Kingdom finds that groups experiencing low home ownership rates at age 30 tend to catch up later in life (Botazzi, Crossley, and Wakefield 2015).

Saving for retirement: The retirement landscape has changed dramatically since baby boomers started to enter the labor market in the mid-1960s. In the United States, employers (particularly those in the private sector) have increasingly switched from generous defined-benefit pension plans, with employer-provided guaranteed retirement income, to defined-contribution account pensions, for which the burden of saving for and managing retirement wealth and income falls on employees’ shoulders during their working years and in retirement. In other parts of the world, rapidly aging populations have led many countries to undertake reforms to their public pensions, which have generally reduced their overall generosity. Millennials thus have greater responsibility for managing and growing their retirement savings and greater uncertainty about how much wealth and income they will be able to live on in retirement. (See “Pension Shock,” in this issue of F&D.)

Despite this shift from defined-benefit to defined-contribution plans, younger generations in the United States are participating in retirement plans at higher rates than earlier generations. Participation trajectories declined after the Great Recession, however, particularly for millennial households, and it remains to be seen whether these declines will reverse over time (Devlin-Foltz, Henriques, and Sabelhaus 2016).

Uncertain future

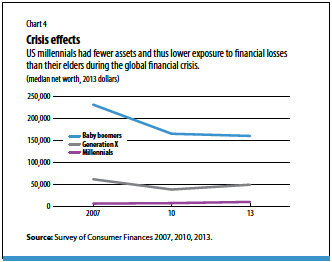

Millennials, Gen Xers, and baby boomers all experienced the economic turmoil of the Great Recession. But because each cohort was at a different stage, the recession affected each differently. Compared with the two previous generations, millennials had fewer assets and thus lower exposure to financial losses during the crisis (see Chart 4). And after the Great Recession, millennials and Gen Xers began accumulating wealth again, while baby boomer net worth has stalled. Although millennials have less wealth than their baby boomer parents at the same age, the median millennial’s net worth increased more than 40 percent between 2010 and 2013, and they still have much of their working lives ahead to recover further and continue to accumulate wealth. If millennials do eventually decide to buy homes or put away a nest egg for retirement, they may have the chance to begin when markets are on an upward trajectory, allowing them to reap the gains of future economic growth.

Millennials are now the largest living generation in the United States, having overtaken baby boomers in 2015. Through their sheer size, this cohort has the potential to wield substantial influence on the macroeconomy as they consume, save, and borrow, both now and far into the future as they reach their golden years. Only time will tell whether the recent trends described here are fleeting or represent a permanent shift in millennials’ financial habits and wealth.

Lisa Dettling and JOANNE W. HSU are senior economists at the Board of Governors of the US Federal Reserve System. The analysis and conclusions set forth are those of the authors and do not indicate concurrence by other members of the research staff or the Board of Governors.

References

Botazzi, R., T. F. Crossley, and M. Wakefield. 2015. “First-Time House Buying and Catch-up: A Cohort Study.” Economica 82 (S1): 1021–047.

Dettling, Lisa J., and Joanne W. Hsu. 2014. “Returning to the Nest: Debt and Parental Co-Residence among Young Adults.” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2014-80, Federal Reserve Board, Washington, DC.

Devlin-Foltz, Sebastian, Alice Henriques, and John Sabelhaus. 2016. “Is the U.S. Retirement System Contributing to Rising Wealth Inequality?” Journal of the Social Sciences 2 (6): 59–85.

Looney, Adam, and Constantine Yannelis. 2015. “A Crisis in Student Loans? How Changes in the Characteristics of Borrowers and in the Institutions They Attended Contributed to Rising Loan Defaults.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (Fall): 1–89.

Martins, Nuno C., and Ernesto Villanueva. 2009. “Does Limited Access to Mortgage Debt Explain Why Young Adults Live with Their Parents?” Journal of the European Economic Association 7 (5): 974–1010.