Global Finance Resets

Finance & Development, December 2017, Vol. 54, No. 4

The decline of cross-border capital flows signals a stronger global financial system

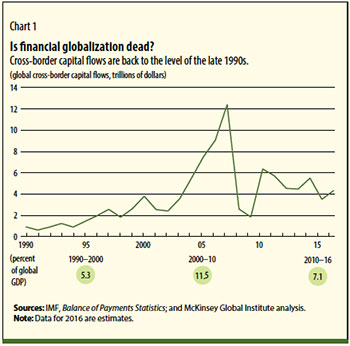

A decade after the global financial crisis began, the landscape of global finance is much altered. Gross cross-border capital flows (foreign direct investment, purchases of bonds and equities, and lending and other investment) have fallen substantially since the precrisis era and, relative to world GDP, are back to the level of the late 1990s (see Chart 1). While all types of capital flows have shrunk, cross-border lending accounts for more than half of the overall decline. This phenomenon reflects a broad retreat from overseas business and a shift away from cross-border wholesale funding by major European and some US banks.

Does this mean that financial globalization has lurched into reverse gear? Our new research finds the answer is no. The global financial system remains deeply interconnected when measured by the stock of foreign investment assets and liabilities. What is emerging from the rubble appears to be a more risk-sensitive, rational, and potentially more stable and resilient version of global financial integration—an ultimately beneficial outcome.

Shift in the landscape

Before the crisis, many of the largest European, UK, and US banks launched bold global expansions, pursuing every avenue for international growth. They built banking businesses for retail and corporate customers in new regions, amassed large portfolios of foreign assets, such as subprime mortgage securitizations and commercial real estate, and increasingly relied on short-term cross-border interbank funding.

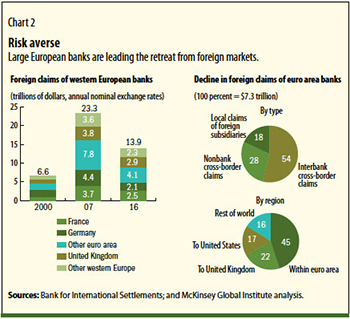

But horns are now drawn in and capital is being conserved. Risk is out, and conservative banking—even “boring” banking, as former Bank of England Governor Mervyn King put it—is in. The largest Swiss, UK, and some US banks have all been part of the broad retreat, but nowhere has the reversal been more dramatic than among euro area banks (see Chart 2).

After the introduction of the euro on January 1, 1999, euro area banks expanded beyond their national borders into all corners of the single currency area. Given the common currency and a largely common rule book, country risk was downplayed or ignored. The stock of their foreign claims (including loans by their foreign subsidiaries) grew from $4.3 trillion in 2000 to $15.9 trillion in 2007. Most of that growth came from lending and purchases of other foreign assets within the euro area. But also important were the growing financial ties—and particularly interbank markets—linking banks in the euro area, London, and the United States.

But much of the banks’ foreign expansion was based on misjudged risks or misguided strategies that came back to bite them. Some European banks bought AAA-rated tranches of US subprime mortgage-backed securities that subsequently produced large losses. Dutch, French, and German banks became directly and indirectly involved in the Spanish real estate bubble and suffered when it burst. Austrian banks expanded far into eastern Europe and even central Asia but have since retrenched, and Italian banks were heavily exposed in Turkey, where risk-adjusted margins proved lower than expected. There was an element of herd behavior: seeing some major banks aggressively expanding abroad in pursuit of high-margin business, many others followed suit.

Since the crisis, that trend has reversed: Foreign claims of euro area banks have slumped by $7.3 trillion, or 45 percent (although they are still substantially higher than they were when the single currency came on the scene). Nearly half these claims have been on other borrowers in the euro area, particularly other banks. The perception that lending anywhere within the common currency area was quasi-domestic—and therefore low risk—proved illusory. Claims between euro area banks and those in the United Kingdom and the United States have similarly evaporated.

This retreat is a rational response—in the euro area and beyond—to a reassessment of the risk of cross-border transactions. On reflection, it has become clear to many banks that margins and revenues on foreign business were lower than they were in domestic markets, where they had both scale and local knowledge—or at least that foreign business was not worth the added risk. Banks are now under sustained pressure from regulators, shareholders, and creditors to become more conservative. New international capital and liquidity requirements raise the costs of holding all assets, and new surcharges imposed on systemically important banks penalize the added scale and complexity of various business lines, including foreign operations; banks have carefully pruned their foreign operations in response. Some central bank programs enacted after the crisis to restore financial stability, such as the Bank of England’s Funding for Lending scheme or the European Central Bank’s Targeted Longer-term Refinancing Operations, gave banks an incentive to lend to domestic borrowers rather than foreign ones.

Major global banks have sold off some foreign businesses, exited some foreign markets altogether, or simply allowed maturing loans to expire. According to Dealogic, a provider of financial data and analysis, banks have divested more than $2 trillion in assets since the crisis. As a result, the balance sheets of most European banks have shifted significantly toward domestic assets. The three largest German banks—Deutsche Bank, Commerzbank, and KfW—held two-thirds of their total assets in foreign markets on the eve of the crisis; today, that proportion has shrunk to one-third.

Dutch, French, Swiss, and UK banks have likewise reduced foreign business. US banks have long been less international than their European counterparts, given their huge domestic market, but even so some have cut back. Citigroup had retail banking operations in 50 countries in 2007; today that figure is 19.

While European and US banks retreat to their home markets, banks in other regions are expanding abroad, although it remains to be seen whether this expansion will prove to be profitable or sustainable. The four large Canadian banks now have half of their assets outside of Canada, mainly in the United States; Japanese banks have also expanded abroad. The so-called Big Four Chinese banks have rapidly expanded foreign lending, largely to finance Chinese companies’ outward foreign direct investment.

More stability ahead

We should not mourn the realignment of cross-border banking. The frothy pinnacle of global capital flows in the years leading to the crisis is not an appropriate benchmark against which to judge the state of financial globalization. There is no consensus on the optimal level of capital flows, but today there is scant evidence of a shortage of capital flowing to either developing or advanced economies.

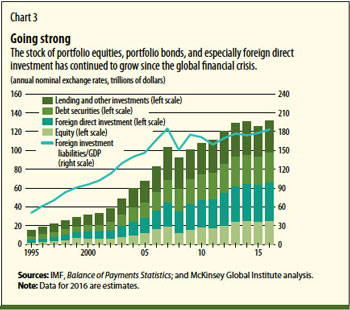

Rather than signaling an end to financial globalization, recent developments point to the emergence of a more stable and resilient version. Financial markets around the world remain deeply interconnected. Although annual flows of new capital have diminished significantly, the stock of global foreign direct investment, portfolio equities, and portfolio bonds has continued to grow since the crisis, albeit much more slowly than in the years that preceded it (see Chart 3). Globally, 27 percent of equities around the world are owned by foreign investors, compared with 17 percent in 2000. In global bond markets, 31 percent of bonds were owned by a foreign investor in 2016, compared with 18 percent in 2000. Lending and other investment are the only component of the stock of foreign investment assets and liabilities that has declined since the crisis.

There are three reasons why the future of financial globalization may potentially be more stable than the past, at least for the medium term.

First, the mix of cross-border capital flows has changed quite significantly, and in ways that should promote stability. Since the crisis, foreign direct investment has accounted for 54 percent of cross-border capital flows, up from 26 percent before 2007. Given the new realities of bank regulation and shareholder scrutiny, it is unlikely that the volume of cross-border lending will return to precrisis levels anytime soon. This shift toward foreign direct investment will promote stability in cross-border financial flows. Because foreign direct investment reflects companies’ long-term strategies regarding their global footprint, it is by far the least volatile type of capital flow. Portfolio purchases of equities and bonds are also less volatile than cross-border lending, and these have comprised over 40 percent of total capital flows since the crisis. Cross-border lending, and particularly short-term lending, is by far the most volatile type of capital flow; its retreat should be welcomed.

The second potential source of greater stability in financial globalization is the steady growth of migrants’ remittances to their home countries. These flows are even more stable than foreign direct investment and have grown thanks to a rise in global migration. Remittances are not counted as a capital flow in the national balance of payments, and traditionally they were quite small. But today they are a substantial source of finance for developing economies. By 2016, remittances to these economies totaled almost $480 billion, compared with just $82 billion in 2000 and $275 billion in 2007. They now equal 60 percent of private capital flows (foreign direct investment, portfolio equity and debt flows, and cross-border lending) and are three times the size of official development assistance. It seems likely that remittances will continue to grow as global migration continues to rise and technologies such as blockchain and mobile payments make them easier and cheaper to send.

A third potential source of greater stability in global finance is the ebbing of the global savings glut that arose prior to the crisis. Global imbalances in financial and capital accounts shrank from 2.5 percent of world GDP in 2007 to 1.7 percent in 2016. This lowers the risk that a sudden unwinding of these imbalances could create exchange rate volatility and balance of payments crises in some countries. Moreover, today the deficits and surpluses are spread over a larger number of countries, and the large imbalances in China and the United States have subsided. There is debate today among economists about whether the smaller global imbalances are likely to persist.

No room for complacency

None of these developments is an invitation to complacency. Gross capital flows remain volatile, potentially creating large fluctuations in exchange rates for developing economies. A tightly interwoven global financial system inexorably comes with a risk of crises and contagion. And asset bubbles and crashes are as old as markets themselves.

If we have learned anything from the past, it is that stability is hard-won and all too easily lost. Just as we are beginning to discern new patterns in global financial integration after the wrenching change of the past 10 years, a new—and game-changing—disruption is coming in the form of digitalized finance. Increasingly widespread use of new financial technologies, such as digital platforms, blockchain, and machine learning, will likely broaden participation in cross-border finance and accelerate capital flows. There will be huge opportunities, but also intense competition. None of us yet knows what new risks may arise as a result of even quicker flows of capital around the globe, but vigilance and a keen eye for the next threat to stability will be vital.

Susan Lund is a partner at the McKinsey Global Institute, based in Washington, DC, and Philipp Härle is a senior partner at McKinsey & Company and leader of its global banking practice, based in Munich.

This article is based on “The New Dynamics of Financial Globalization,” published by the McKinsey Global Institute in August 2017.