Typical street scene in Santa Ana, El Salvador. (Photo: iStock)

IMF Survey : Big Banks Benefit From Government Subsidies

March 31, 2014

- Banks deemed ‘too important to fail’ borrow at lower rates, take bigger risks

- Policymakers should aim to remove this advantage to protect taxpayers, ensure level playing field, promote financial stability

- Reforms helped reduce the implicit public subsidy to big banks

Reforms since the global financial crisis have reduced, but not eliminated the implicit government subsidy afforded to banks considered “too important to fail” because their failure would threaten the stability of the financial system.

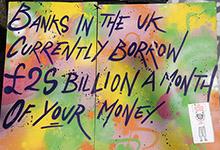

Protest placard in the United Kingdom: banks considered ‘too important to fail’ still benefit from implicit subsidies from taxpayers (photo: Roberto Herrett/Corbis)

GLOBAL FINANCIAL STABILITY REPORT

In its latest analysis for the Global Financial Stability Report, the IMF shows that big banks still benefit from implicit public subsidies created by the expectation that the government will support them if they are in financial trouble. In 2012, the implicit subsidy given to global systemically important banks represented up to $70 billion in the United States, and up to $300 billion in the euro area, depending on the estimates.

Government support to banks during the crisis has taken different forms, from loan guarantees to direct injection of public funds into banks. The expectation of that support allows banks to borrow at cheaper rates than they would if the possibility of that support didn’t exist. Those lower funding costs represent an implicit public subsidy to large banks.

Subsidy encourages risk-taking

This implicit subsidy distorts competition among banks, can favor excessive risk-taking, and may ultimately entail large costs for taxpayers. While policymakers may need to rescue big banks in distress to safeguard financial stability, such rescues are costly to governments and taxpayers. Moreover, the expectation of government support reduces the incentives of creditors to monitor the behavior of big banks, thereby encouraging excessive leverage and risk-taking.

Recent financial reforms and progress in banks’ balance sheet repair have contained the too-important-to-fail issue, albeit with unequal results across countries. The analysis found that particularly large subsidies persist in the euro area, and to a smaller extent in Japan and the United Kingdom.

“Progress is under way, but the subsidy estimates suggest the issue of too-important-to-fail is still very much alive,” said Gaston Gelos, chief of the Global Stability Analysis Division in the IMF’s Monetary and Capital Markets Department that produced the report.

Banks grew bigger

The IMF said the issue of too-important-to-fail has intensified in the wake of the financial crisis for two main reasons:

• The turmoil that followed the failure of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 forced governments to intervene massively to maintain confidence in the banking sector, and prevent a collapse of the whole financial system. This left little uncertainty about the willingness of governments to support big banks in distress.

• Banks have continued to grow bigger, and there are fewer banks in operation. As a result, estimated implicit subsidies to big banks rose significantly in 2009 in all countries.

In response, policymakers have launched ambitious plans for financial reforms. They required banks to hold more capital to use in case of losses, and strengthened the supervision of global systemically important banks to reduce the probability and cost of failure.

They are working on improving domestic and cross-border resolution frameworks for large and complex financial institutions. In some countries, governments are adopting structural measures to limit certain bank activities.

The IMF analysis suggests that these efforts contributed to a decrease in subsidy values in the recent period. Banks’ balance sheet repair, encouraged by supervisors and regulators, also played a role in the implicit subsidies’ decline.

Policymakers should strengthen reforms

Policymakers have not implemented all policy measures, and they should pursue those under way, the IMF said.

Completely excluding the possibility of government support for big banks may be neither credible nor always socially desirable. Further efforts should aim to reduce the probability of distress in big banks. For instance policymakers can enhance capital requirements, and possibly recoup taxpayers’ costs from those banks through a financial stability tax. This could be based on banks’ liabilities, as is the case in several European countries.

Structural measures to restrict the size and scope of banks can entail efficiency costs if they reduce economies of scale and scope, or increase bank profits with no benefit to the economy as a whole.

The IMF said such policies could be useful in managing risks that are difficult to measure, such as risks of rare but fatal financial events, and address through other tools such as capital and liquidity requirements.

To avoid banks using loopholes to evade unfavorable regulation and negative effects spilling over across countries, the report calls for sustained international coordination. In particular, policymakers need to do more to facilitate the supervision and resolution of cross-border financial institutions.

The IMF plans to release more analysis from its Global Financial Stability Report on April 9.