Typical street scene in Santa Ana, El Salvador. (Photo: iStock)

IMF Survey : History Sheds Light on Governments’ Fiscal Policy Decisions

January 28, 2013

- IMF study gauges countries’ fiscal prudence or profligacy over time

- Database is the most comprehensive currently available

- Data reveal how primary fiscal balances have changed over time

As policymakers across the world are assessing the need for spending cuts and tax increases against the risk of triggering a new recession, a look back at history provides insights from those who grappled with similar challenges in past decades.

Ginza district in Tokyo, Japan, where fiscal prudence in mid-1980s to early 1990s aimed to stabilize debt (photo: Yoshikazu Tsuno/AFP/Getty Images)

Debt & Deficits

A new IMF study looks at the history of budget deficits and fiscal consolidation over the past two hundred years.

The study assembles a historical record of the degree of fiscal prudence or profligacy across advanced and emerging economies—essentially a look at whether countries’ finances tend to run in the red or the black. Covering 55 advanced and emerging economies, it is the most comprehensive database on debts and deficits for such a long historical period.

Primary fiscal balance

The study focuses on governments’ primary fiscal balance, which is the best available proxy for the overall fiscal picture within the government’s control. The primary fiscal balance consists of government revenue less spending, but excludes the interest bill on the debt. In other words, it’s the most accurate reflection of the government’s fiscal policy decisions.

“In practice, prudence and profligacy are not built up overnight—one or even a few years of high or increased spending do not necessarily cause a financial crisis, provided a government’s initial position is strong. Conversely, the academic notion of fiscal sustainability—whereby the net present value of all future fiscal surpluses must be enough to cover today's government debt—is impractical: one cannot expect that in real life, people will wait indefinitely to decide as to whether spending and tax policies are sound,” said Rafael Romeu, one of the authors of the study

In addition to documenting the varying degrees of fiscal prudence or profligacy across countries, the study examines the factors that cause changes in prudence or profligacy. The study finds evidence that high government interest rates and slowing economic growth cause changes in the degree of fiscal prudence across governments.

What the numbers show

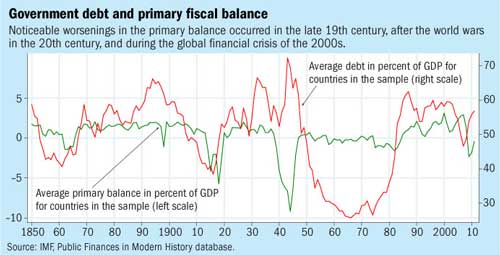

According to the study, fiscal profligacy prevailed and debts began to increase as a share of GDP in the 1970s, as the rate of economic growth slowed down in the aftermath of the oil price shocks. Noticeably higher overall deficits became widespread in the late 1970s and early 1980s. As worldwide interest rates rose, the mid-1980s saw the first attempts to restore fiscal prudence. Throughout the 1990s, fiscal surpluses and significant reductions in public debts were achieved due to broad economic expansion and Maastricht-era consolidations in Europe, as well as greater fiscal restraint in Latin American and other emerging economies in the 1990s and 2000s (see chart).

Among the main insights to be gleaned from the study is the impact of the global financial crisis that began in the late 2000s. The global financial crisis resulted in the most pronounced and pervasive peacetime worsening of the primary fiscal balance, with average primary fiscal deficits in 2008–09 larger than at any other point in history aside from the World Wars.

Turning to individual country developments, the study shows the extent to which each country’s fiscal policy may be considered “prudent” or “profligate” varies over time. To do so, a battery of academic tests for fiscal sustainability are applied and policy periods are summarized as times of “prudence” or “profligacy” for each country at different points in history.

The drivers of prudence and profligacy

Another key finding in the study relates to the driving forces underlying policymakers’ budgetary decisions.

The results show policymakers tend to respond more vigorously—in terms of their decisions on how to spend and raise revenue given changes in the debt levels they face—in response to unexpected changes to longer-term economic growth or borrowing costs. Fiscal profligacy often occurs when the rate of long-term economic growth declines unexpectedly. Fiscal prudence tends to improve when governments face increases in the cost of borrowing.

So, for instance, if policymakers facing rising government debt are hit with the prospect of lower long-term economic growth, their response is more likely to be a loosening of the budgetary purse strings. Likewise, if policymakers face increases in long-term real borrowing rates, they tighten the budgetary purse strings.

The study suggests today’s fiscal policy responses to the global financial and economic crisis will one day be viewed as prudent or profligate depending on whether economic growth returns to its rapid levels experienced prior to the crisis.