Food Security and the Increase in Global Food Prices, Speech by Mark Plant, Deputy Director, Policy Development and Review Department, IMF

June 19, 2008

At Panama Chamber of Commerce, Industry and Agriculture

June 19, 2008

| Download the presentation (English) (954 kb PDF) | Download the presentation (Español) (934 kb PDF) |

Thank you very much for your kind introduction, and to all of you for your presence here today. As a representative of an international institution with a global membership, it is a pleasure to speak in a country that has as its motto "pro mundi beneficio" or "for worldly benefit". It is an aspiration that we should keep in mind as we discuss the important challenge of food security that faces the international community today.

I would like to begin by considering what are the drivers of the sharp increase in food prices—that have redefined the world food situation. The increase has been almost 50 percent in the last year.

The world is experiencing the consequences of an unhappy conjuncture of long-term structural influences and short-term factors. During the past two decades, demand for food has been increasing steadily, reflecting the rise in the world's population, positive improvements in incomes, and the diversification of diets. However, until mid-2004 food prices had been declining, thanks to record harvests and the use of world grain stocks. At the same time, average crop yields were flat or falling, as investment in agriculture, particularly in developing countries, declined. Moreover, low prices, especially for food staples, and distortions in agricultural markets, discouraged production particularly in low-income countries.

More recently, food price increases have become more pronounced, and, coupled with the rapid increase in oil prices, are posing serious economic and political problems.

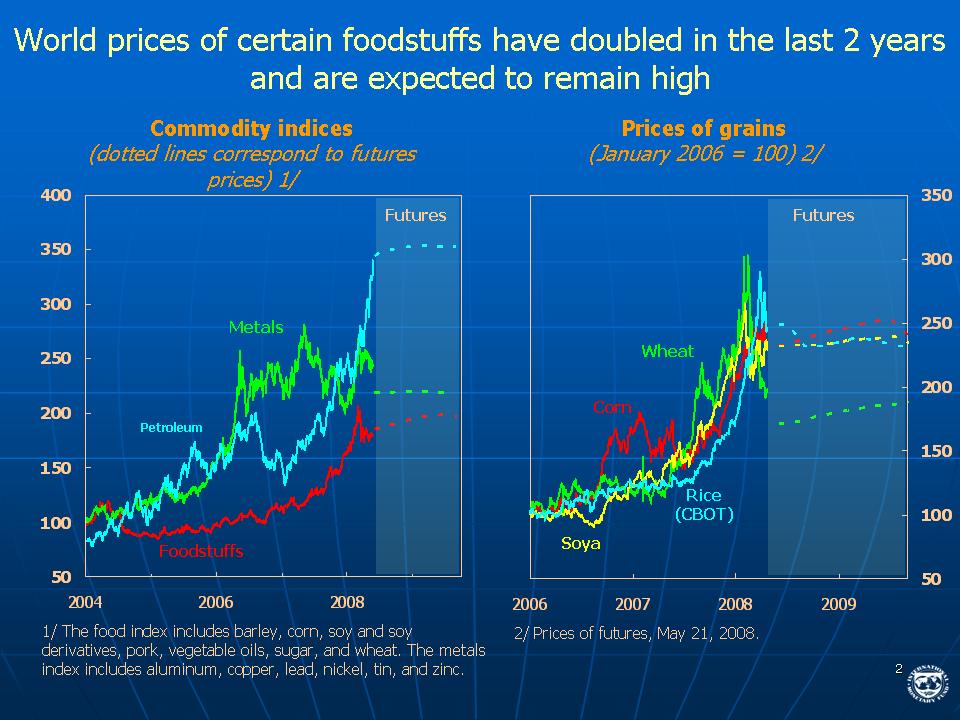

As this slide shows, a rapid rise in commodity and food prices has taken place over the last few years. Note that food (the red line) has been on a more steady climb, as opposed to both metals and oil (the green and blue lines) which have spiked in the last year or so.

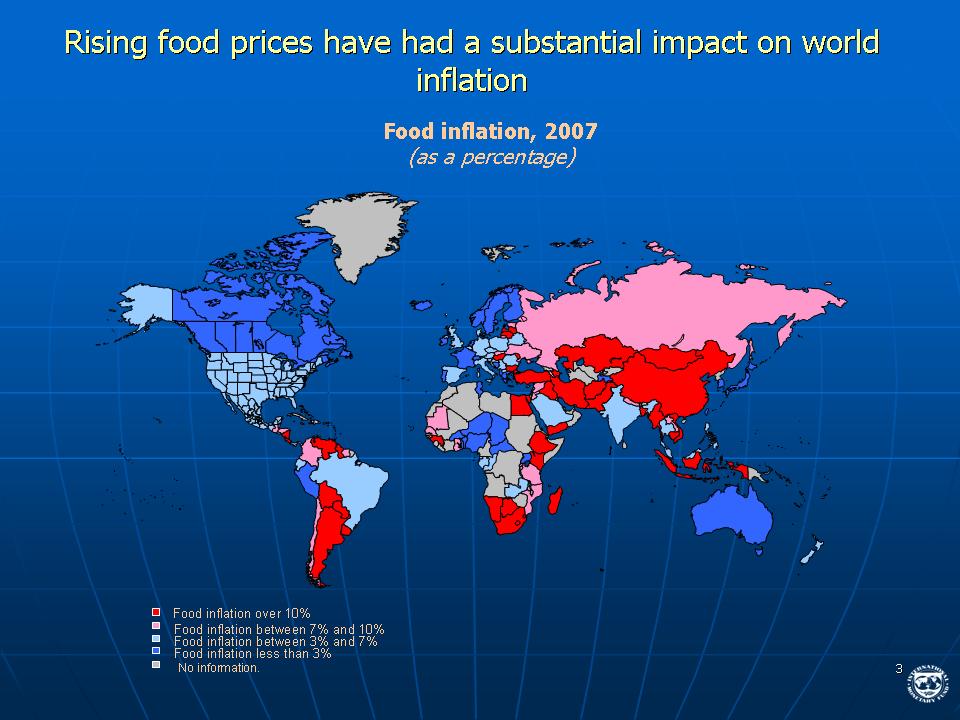

And it is worth noting that food price increases have not been uniform throughout the world.- Asia, the former Soviet Union, southern Africa and parts of Latin America have been particularly hard hit. I will show you a slide on the situation in Central America in a few minutes.

Why have food prices been on the rise since 2004?

First, as I noted before, stocks have been slowly declining since 2000. In addition, there were bad harvests in the past three years. The recent strong growth of emerging and developing countries has been a factor as has rising biofuels production in advanced economies. With biofuels, one begins to see the interaction of higher oil prices with food supplies. And biofuel production has also reflected generous policy support in some countries. Finally, high oil prices have driven up the cost of agricultural inputs, like fertilizers, and transport. Very recently, the introduction of export restrictions in some countries, to protect domestic supplies, tightened world market conditions for some key food crops, like rice. Speculation, hoarding and panic buying may also have played some role.

Looking ahead, food prices are expected to ease gradually in the short term. The price of rice has fallen a bit in the last few weeks, although corn prices continue to rise, especially in light of the floods in the midwest of the United States. But the outlook even for the next couple of years is uncertain and depends on policies put in place now to encourage increased production. Nevertheless, the pressure on food prices from the underlying structural influences will likely remain and keep prices at higher levels than in the past.

Let me turn to impact of the food price shock on food security in the short term.

The immediate problem is essentially a food price crisis rather than a global shortage of food. The rapid increase in food prices has had an adverse impact on poverty, and effectively denied many poor people access to food.

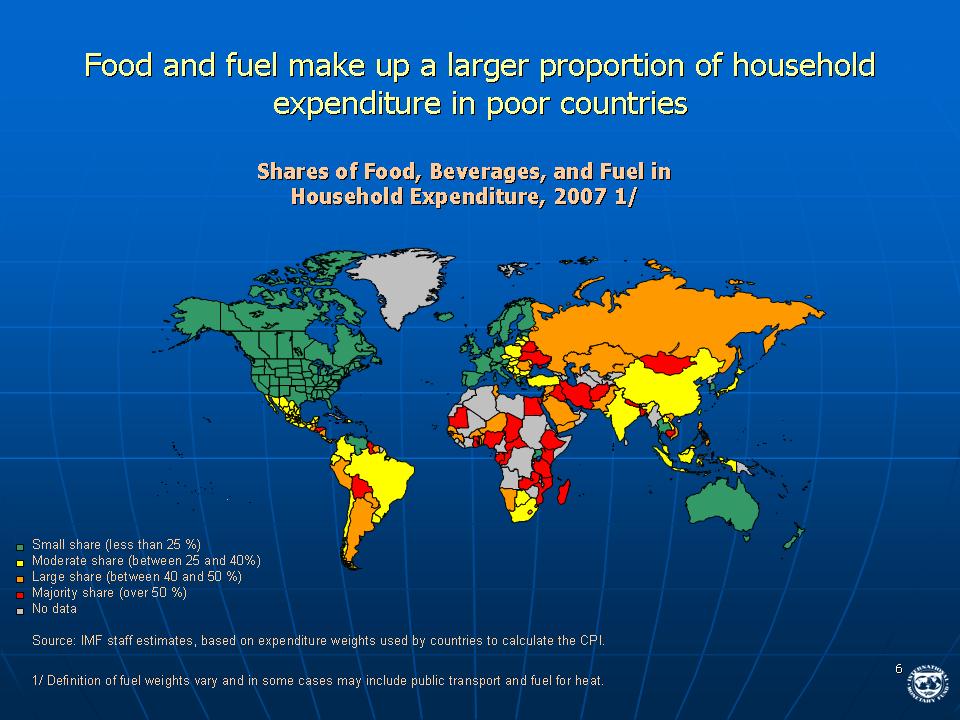

This is mainly because the share of food in household spending is very large in developing and emerging economies, as shown in this slide—the countries highlighted in red and orange have household consumption that is very food intensive.

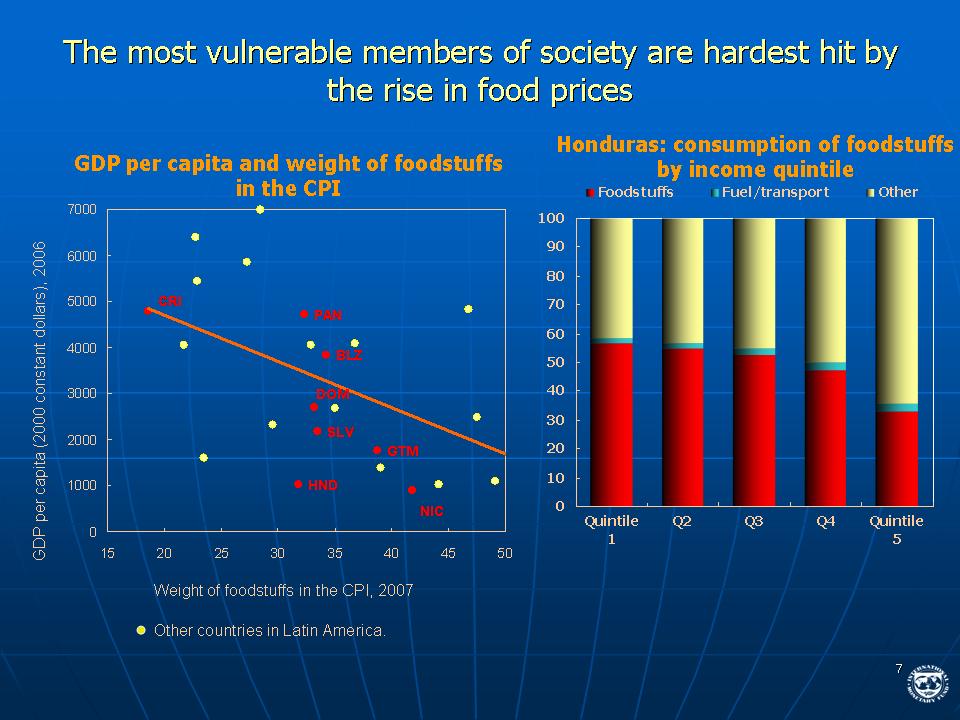

This is particularly true in Central America—these countries tend to have relatively large parts of their consumption bundles allocated to food. And within countries, the poorer spend more of their household income on food, as illustrated with data from Honduras. Indeed, in Central America, poverty levels, which declined this decade, are likely to increase as higher food prices persist. Available data suggest that on average, the cost of purchasing the "canista basket", which reflects minimum nutritional requirements, has risen about 17 percent from March 2007 to March 2008. Therefore the immediate challenge is to get food—or the money to buy food—to those most in need. In this regard, the international response to the World Food Program's call for additional assistance has been impressive.

In the short term, efforts to get food to the most affected countries, and population groups within countries, must be complemented by measures to ease the burden of higher food prices on the poorest people. These measures include scaling up well-targeted social safety nets, expanding conditional cash transfer programs, temporary subsidies on a small number of products vital for the poor, expanding school feeding programs, and food-for work programs. Some countries in this region have taken such measures, including Costa Rica with school feeding programs, supplementary income to the elderly poor, and transfers to poor families. El Salvador has expanded of its cash transfer programs. Panama, El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua have reduced or eliminated tariff on key food items.

But we must avoid policies that have negative effects on countries that rely on food imports. Export restrictions are harmful , not helpful, as are or direct price controls, which distort price incentives and discourage production. Countries should also avoid general subsidies to the extent possible, as these tend to be expensive and don't target those most in need. And often they become entitlements over the longer-term.

At the same time, we must begin to address the long-term factors that are driving up food prices, so as to ensure that supply increases rapidly enough to meet growing demand

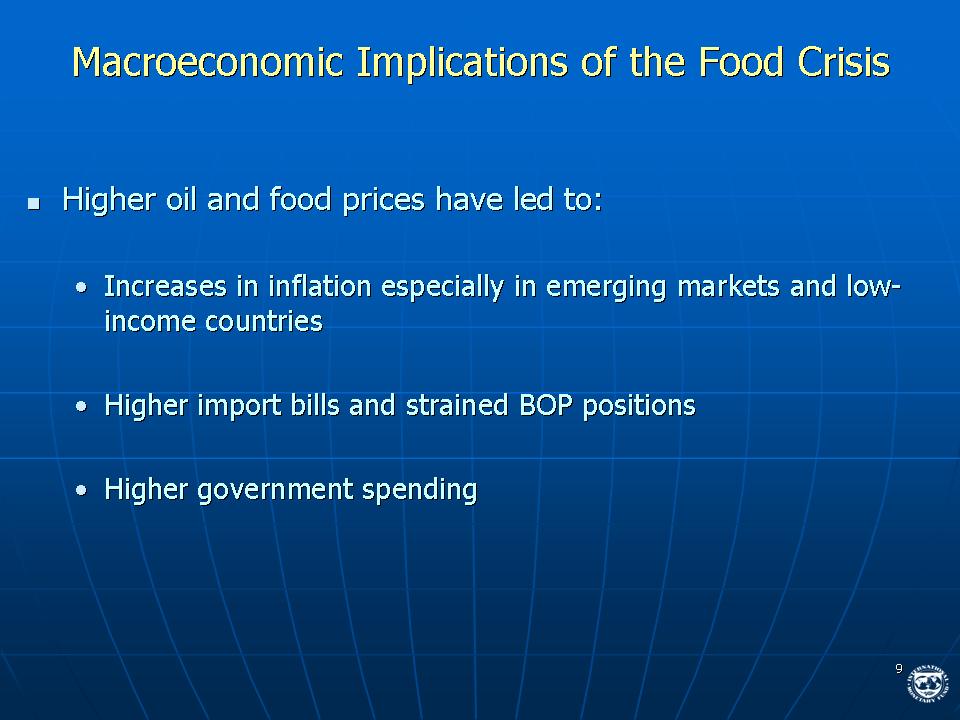

Turning to the IMF's area of expertise, the food crisis and high oil prices are having significant macroeconomic implications, as listed in this slide - pressures on inflation, on the balance of payments and on budgets. These impacts will need to be managed in each country, to ensure that the shocks do not become entrenched as generalized inflation, chronic shortages of foreign exchange, or chronic budget deficits. The key objective should be to preserve the gains made over the past few decades in establishing sound macroeconomic environments for growth. Let me talk about each of these three pressure points—prices, balance of payments and budgets.

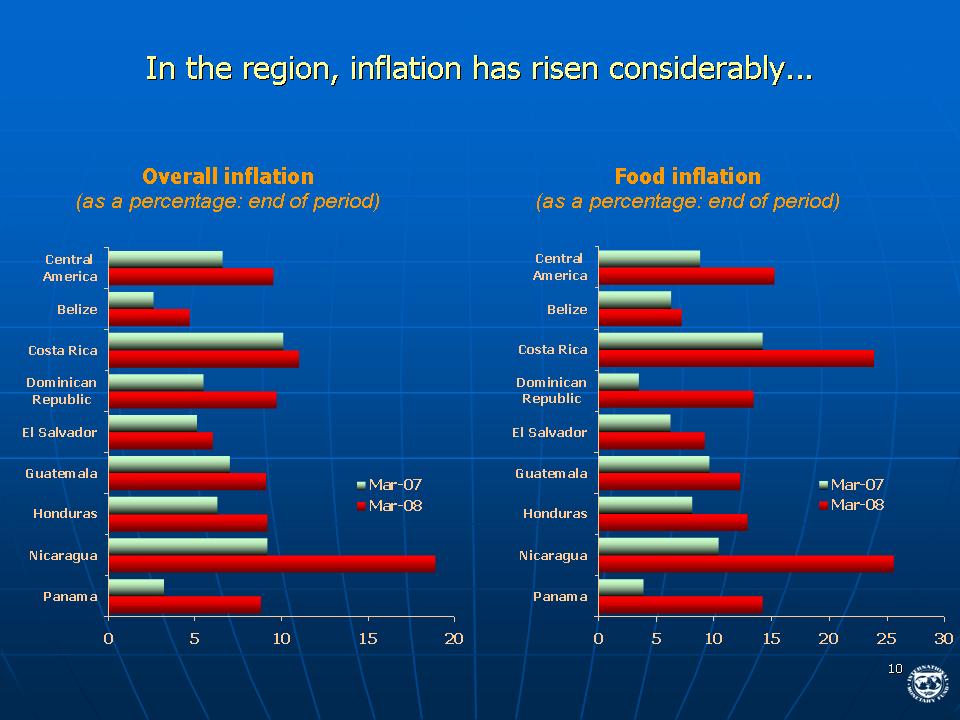

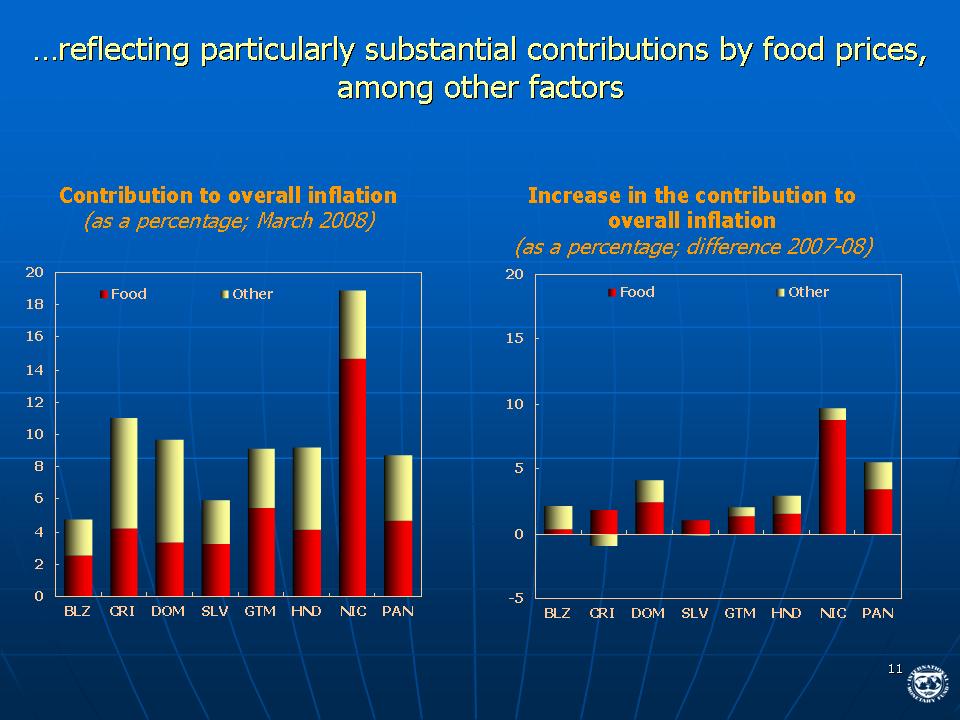

Higher oil and food prices have already led to substantial increases in overall inflation, particularly in emerging markets and low-income countries. In Central America, average headline inflation, year-on-year was 11 percent in March 2008, with food price inflation doubling.

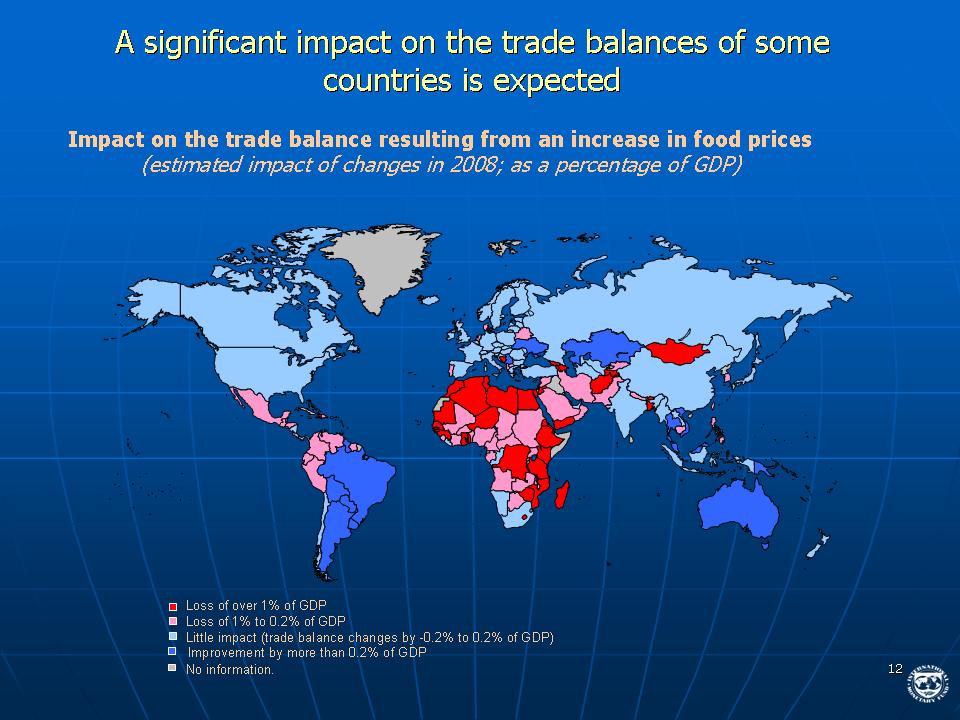

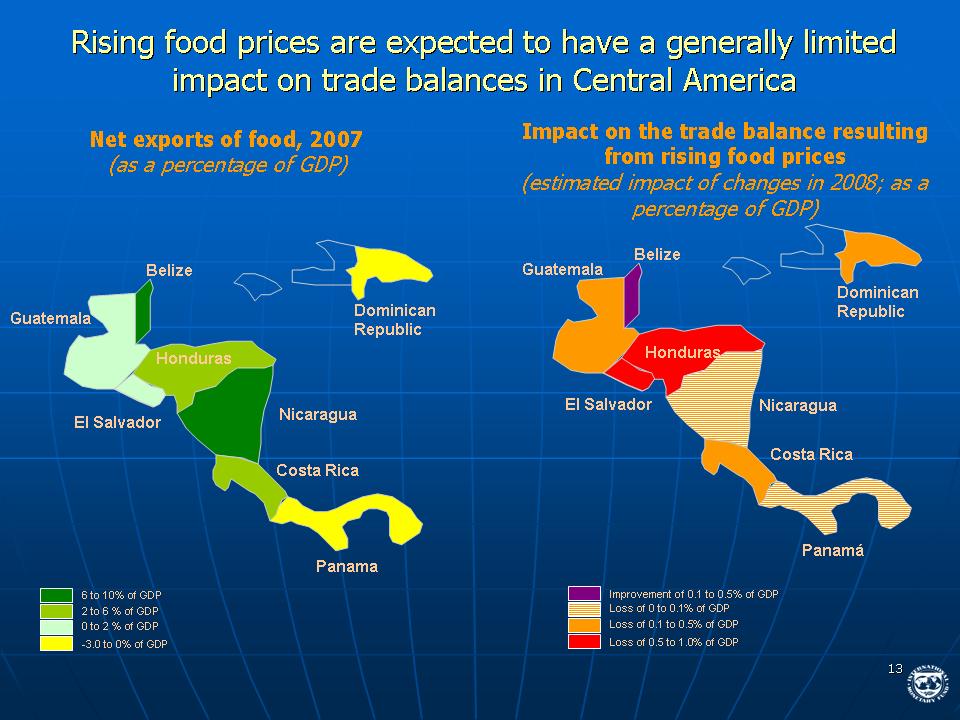

The sharp increases in food and fuel prices, have led to higher import bills and strained the balance of payments position of many countries. Central America, as a net importer of fuel has seen its oil import bill rise by over 2.5 percent of GDP between 2004 and 2007. While the region as a whole is a net food exporter, the food price shock has largely affected cereals, of which the region is a net importer.

As a result, the combined price shocks have led to deterioration in the region's trade balance in 2007, and is expected to do so again in 2008, although the effect will vary across the region. Fortunately, reserve positions of the Central American governments have generally remained strong and, thanks to continued capital inflows, the overall balance of payments position has not experienced stress, and depreciation pressures have not emerged.

Now, a word of caution about the strain on government budgets. All of the domestic measures to cushion the burden of rising prices have a fiscal cost—either lower revenues from reduced taxes and tariffs, or higher expenditures on social safety nets or support measures for small farmers. Thus, governments have yet another challenge to confront in allocating scarce resources.

What can be done to confront these macroeconomic challenges? In due course, permanent price shocks will need to be fully passed through to consumers and producers. However, short-term measures can and should be used to mitigate the adverse short-term impacts. Of course, the task of policy makers is complicated by the uncertainty about the extent to which recent increases in food and fuel prices are permanent. But we should ensure short-term measures minimize disincentives for long-run supply responses.

A key macroeconomic objective should be to limit the second round effects of external price shocks to avoid the risk of rising inflation. Such risks are particularly of concern for countries where domestic demand has been growing strongly. The monetary authorities will need to give clear signals to bring inflation progressively down by tightening monetary policy. Fiscal policy will need to be tightened to reinforce the monetary response, especially in rapid growing countries where demand pressures are already contributing to inflation. Blanket wage increases in response to higher prices should be avoided, so as to help contain inflation expectations and prevent wage-price spirals.

It will be important for governments to assess, contain, and monitor the cost of mitigating measures, and some tough budgetary choices will need to be made. Some governments that are in good fiscal positions will have scope to spend more money. Others will need to raise revenue, reduce other types of spending, borrow, or secure foreign aid. It is important that mitigating measures be limited in both size and duration—the food price crisis should not provide an excuse for new entitlements.

But this is not just a country-by country problem—it is a problem that requires a coordinated international response. Let me say a few words about what the international community and the IMF are doing.

The cost of the longer term agenda is large, and financial support from the international community will be needed. However, it is important that these resources be additional to existing development assistance, and not be mobilized at the expense of support to other sectors, especially health and education. The UN High-Level Task Force on the World Food Price Crisis has presented a Comprehensive Framework for Action, which puts forward a consistent set of recommendations for actions in the immediate and longer term, that seek to bridge the traditional divide between humanitarian assistance and development needs.

For our part, the IMF is already engaged in helping countries address the global price shocks. We are working actively with national and international partners in responding to the many challenges, particularly on the macroeconomic front.

We are providing policy advice on the design of targeted social measures to alleviate the effects on the poorest, and helping countries to assess the fiscal cost of their policy responses. At the same time, we are helping countries to create the fiscal space for these and other needed expenditures while maintaining sound and sustainable macroeconomic policies.

We are advising country authorities on how to contain the inflationary pressures generated by higher food and fuel prices. In particular, we are providing advice on how to contain the second round price effects.

The IMF is also assessing the net impact of the energy and food price hikes on countries' balance of payments, and we stand ready to provide rapid financial assistance where needed. We have already doubled our financial assistance to five low-income countries because of increases in prices of food and imported fuel—Burkina Faso, Kyrgyz Republic, Mali, Niger and Benin—and we are discussing additional support for another 11 countries. In two days time our Board will be considering Haiti's request for additional support. We are also considering adapting some of our financing instruments to make them more easily accessible to countries in urgent need.

On trade policies, the IMF has been vocal in calling for the elimination of policies that distort global food markets, including eliminating biofuels subsidies. We are also pressing for a rapid and ambitious conclusion to Doha Round trade talks, which should include agreements on agriculture that help to broaden and stabilize international food trade and foster efficient agricultural production.

To conclude, the crisis can be managed if we each play our part and do the right things within a coherent global framework for action. In partnership with our member countries and the international community, the IMF stands ready to play its role in the response to the global food crisis.

IMF EXTERNAL RELATIONS DEPARTMENT

| Public Affairs | Media Relations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-mail: | publicaffairs@imf.org | E-mail: | media@imf.org | |

| Fax: | 202-623-6220 | Phone: | 202-623-7100 | |