Debt: Use It Wisely - Press Conference Opening Remarks

October 6, 2016

In this issue of the Fiscal Monitor, we look at private and public debt around the world:

- Our first finding is that global debt is at record highs and rising.

- But there is quite a bit of heterogeneity within and across groups of countries.

- Second, high debt levels are costly as they often end up in financial recessions than are deeper and longer than normal recessions.

- Finally, we conclude that fiscal policy can do more to foster growth and stability.

Let me walk you through the key elements of our analysis.

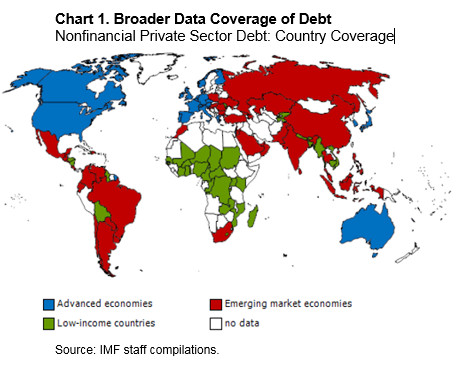

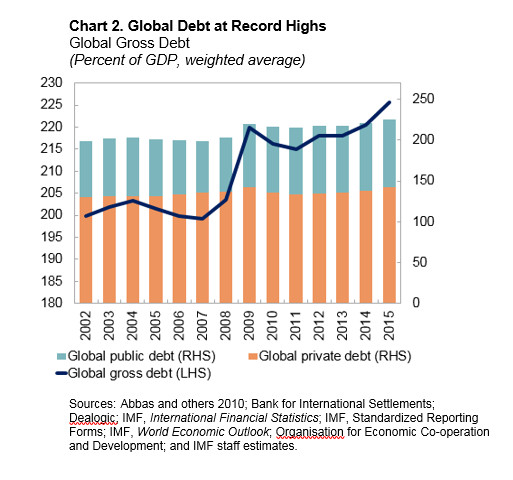

Global debt is at record highs and rising. Based on a novel database (Chart 1), we find that over the last fifteen years the debt of the nonfinancial sector has increased significantly reaching $152 trillion by 2015 (225 percent of world GDP). About two-thirds (or $100 trillion) is the debt of the private sector. The remainder is public debt, which increased from below 70 percent of GDP at the beginning of the century to almost 85 percent in 2015 (Chart 2).

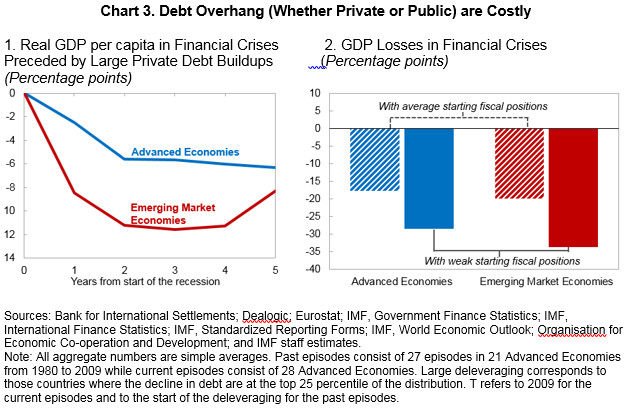

Excessive private debt is a major headwind against the global recovery and a risk to financial stability. The Fiscal Monitor shows that rapid increases in private debt often end up in financial crises. Financial recessions are longer and deeper than normal recessions (Chart 3, left-hand side). But public debt also matters. Entering a financial recession with a weak fiscal position results in even larger output losses (Chart 3, right-hand side). This is especially the case for emerging market economies which tend to cut government spending in times of crisis, reflecting tighter financing conditions.

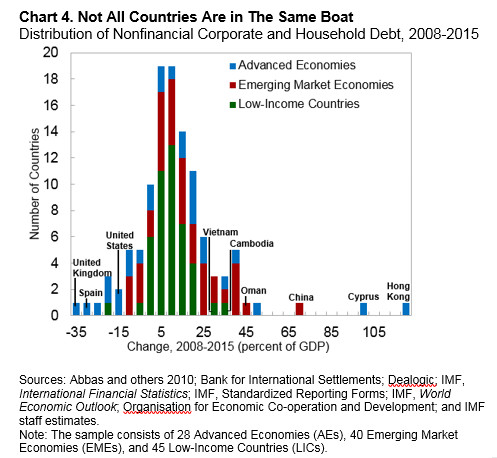

However, debt is not high everywhere. Private debt is concentrated in advanced and a few emerging market economies. In advanced economies, which were at the epicenter of the global financial crisis, deleveraging has been uneven and in many cases private debt has continued rising (Chart 4). Public debt has also surged in these countries partly due to the migration of bad debt of the private sector on to the government balance sheet. Private debt is also high in some systemic emerging markets economies, including China. At the other end, debt levels in low-income countries are generally low but have been on the rise recently. The sharp diversity across countries is a reminder of the need to tailor policy diagnosis and prescription to the specific conditions prevailing in each country: no one size fits all.

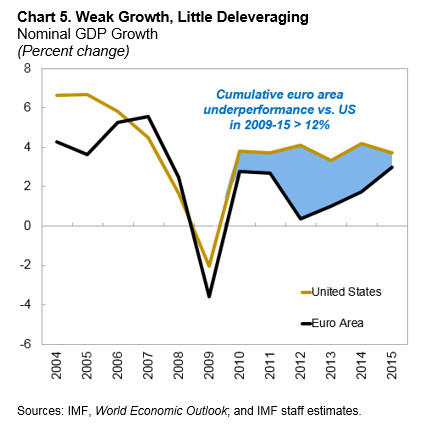

Low nominal growth is a major driver behind slow deleveraging in advanced economies. Comparing the United States and the euro area is illustrative. In the run-up to the crisis, the former experienced a larger increase in private debt but it also reduced it much more in its aftermath. The United Sates also enjoyed higher nominal growth—more than 10 percentage points in cumulative terms over the period since 2007 (Chart 5). The weak macroeconomic environment also explains about half of the increase in public debt, since the onset of the global financial crisis. It is clear that deleveraging is made difficult by low nominal growth.

Let me now turn to policy priorities.

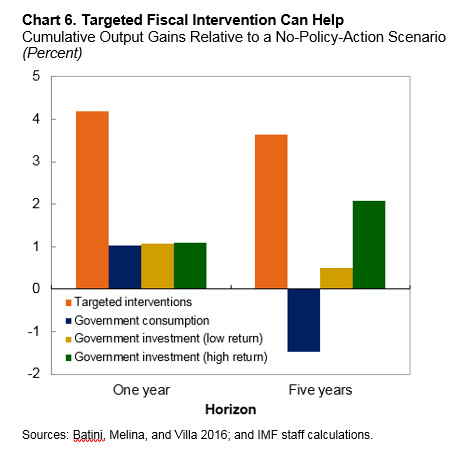

Fiscal policy can do more to restore growth and stability. Targeted fiscal interventions in the form of government-sponsored programs to help restructure private debt and public support for financial sector restructuring can be very effective in reducing output losses associated with private sector deleveraging (Chart 6). This type of policies could be particularly useful in China. But in order to work, they need to be adequately designed and subject to strong governance principles. As political unpopular as these measures may be, the Fiscal Monitor shows that inaction or delayed action can be very costly.

But fiscal policy cannot do it alone. A comprehensive, consistent, and coordinated approach is what we need. Comprehensive action using all three policy prongs—monetary, fiscal, and structural—harnesses the synergies across policies. Consistent policy frameworks, over time, can anchor long-term inflation expectations and lead to an eventual sustainable downtrend in government debt-to-GDP ratios.

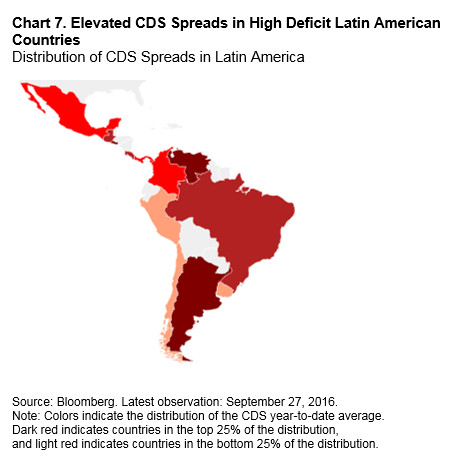

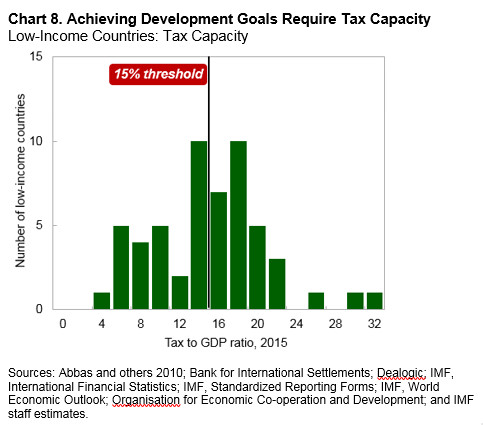

In emerging-markets and low-income countries the focus should be on growth-friendly fiscal policy. In some of these countries fiscal deficits have increased rapidly over the last year on the back of lower commodity prices and a less supportive global environment. While the adjustment in many of these countries is inevitable, the speed of adjustment will depend on available buffers. Improving the quality of public finances and strengthening fiscal frameworks would enhance policy credibility and resilience. In Latin America, financing costs rose the most where fiscal deficits increases were coupled with the lack of credible fiscal frameworks (Chart 7). Among low-income countries, particularly oil producers, adjustment has been slow and piecemeal, very often forced by the lack of financing and effected mainly through across the board spending compression. Tax capacity, in many of these countries, is insufficient, hampering their ability to close infrastructure gaps and to achieve other sustainable development goals. (Chart 8)

History has taught us that it is very easy to underestimate the risks associated with private debt during the upswing . Therefore, it is crucial to have in place measures to prevent excessive debt buildup. Regulatory and supervisory policies should ensure the monitoring and sustainability of private debt. Tax distortions favoring debt over equity should be gradually eliminated.

To conclude: global debt is at record highs and rising. But the global debt landscape is diverse. Fiscal policy can do more to restore nominal growth, facilitate adjustment and build resilience. But it cannot do it alone, and needs to be anchored in a credible medium-term policy framework.

IMF Communications Department

MEDIA RELATIONS

PRESS OFFICER:

Phone: +1 202 623-7100Email: MEDIA@IMF.org