A distinguished figure from the past appears at the IMF on its 75th anniversary

“ID. I gotta see some ID.”

The elderly gentleman, attired elegantly in a three-piece suit and striped tie, stared back blankly. The guard gave an exaggerated sigh. “Who are you? What’s your name?”

“Keynes. John Maynard Keynes. Lord Keynes.”

“Look, buddy, I don’t care if you’re Lord of the Rings. I still need to see some ID before I let you into the building.”

A nameless bureaucrat, scurrying past, late for work, stopped dead in his tracks and whirled around. It was Keynes! He recognized the face from the bronze bust in the executive boardroom. “Excuse me,” he said, flashing his pass at the guard, “I’ll take care of this gentleman.”

“Make sure he gets a visitor pass,” the guard called after them.

They entered IMF Headquarters. “Please, Lord Keynes, won’t you have a seat, while I…”

“Weren’t you expecting me? Didn’t you receive my telegram?”

“Um…I’m afraid not. Let me call the Managing Director’s office. I’m sure they will sort it out.”

“Well, I am a bit late. American trains, you know, never punctual…” muttered Keynes, as he sat on the hard leather bench, appearing a bit dazed by the wide array of flags that adorned the lobby.

It was almost 20 minutes before the bureaucrat reappeared. “The Managing Director will be pleased to meet you now,” he announced.

“That’s most kind of him…um, what’s his name?”

“Lagarde. Christine Lagarde.”

“A lady? A French lady?”

The bureaucrat nodded.

“Oh, well, I suppose we have the No. 2 slot?”

“The First Deputy Managing Director is an American, David Lipton.”

“Ah, of course, the Americans. But surely, we have the No. 3 position? I mean, Great Britain has the second largest quota.1 I should know: I negotiated it myself.”

The bureaucrat coughed apologetically. “Actually, Japan has the second largest IMF quota now. Followed by China and Germany. But the United Kingdom has the fifth largest quota—tied with France,” he added consolingly.

Keynes was just digesting this piece of information when he was ushered into the Managing Director’s office.

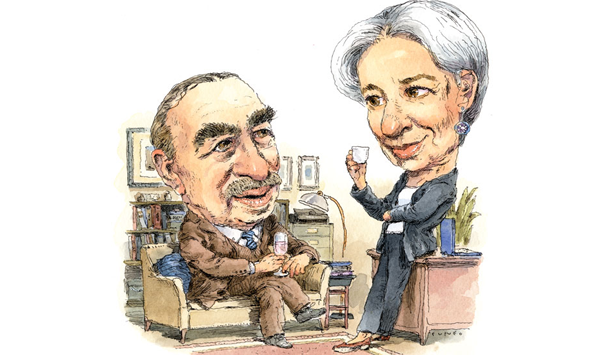

“Lord Keynes, what an honor to meet you.”

“Enchanté, Madame.”

“I am so sorry that we haven’t arranged a better reception for you. To be honest, we weren’t really expecting…”

Keynes smiled thinly. “I know. I’ve been ‘in the long run’ for some time now.2 But I couldn’t resist visiting the Fund today, on its 75th birthday.”

Lagarde motioned him to the sofa, strode over to her Nespresso machine, and began to prepare two cups of coffee.

“So, tell me,” said Keynes, “Has the IMF been a success? What’s been happening? I understand there’ve been some changes since the Conference.”

“I scarcely know where to begin,” replied Lagarde. “So much has changed.”

“Well, the Articles. We labored so hard to negotiate every word. I trust they haven’t changed.”

“On the whole, no. But there’ve been a few amendments.”

“Such as?”

“The first amendment was for the creation of the SDR—the special drawing right. It’s a sort of … well, it’s complicated. But think of it as a virtual currency among central banks. It’s to provide liquidity to the international monetary system when it’s needed. We did a massive allocation in 2009.”

“Sounds like my bancor!”

“Yes, exactly,” Lagarde laughed. “I forgot. I need hardly explain how the SDR works to you. Let’s see, what else? I suppose that the other big change was the second amendment, which legitimized floating exchange rates.”

“Floating rates! But we established the IMF precisely to get stability in the foreign exchanges after the utter chaos between the wars.”

“The Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates collapsed in the early 1970s.”

“Then why wasn’t the IMF shut down?”

“Oh, the world soon discovered it still needed us. Besides, even with floating rates, we exercise firm surveillance over members’ exchange rate policies to make sure they do not manipulate their currencies and gain unfair trade advantage.”

“Indeed. And do they listen to you?”

Lagarde gave a little laugh. “Well, not always, perhaps,” she conceded. “The United States is always complaining about surplus countries not allowing their currencies to appreciate—it used to be Germany and Japan that were the main culprits. Until recently it’s been China. A few years ago, we were even accused of being ‘asleep at the wheel’ on our most fundamental responsibility of surveillance.’ ”3

“Ah, I told Harry Dexter White at the time: You’re hobbling the IMF’s ability to force surplus countries to adjust—I wanted symmetric penalties for surplus and deficit countries, you know. But White and the US Treasury gang resisted strongly. I warned White, You won’t always be a surplus country, and then you’ll be sorry. He used to say, ‘That doesn’t matter—the United States will always champion free trade.’ Presumably that’s still the case?”

“Oh, quite,” Lagarde replied dryly.

“So central banks no longer intervene in the foreign exchange markets?”

“Not if they have floating rates. They’re not supposed to, except under disorderly market conditions.”

“Aren’t markets always disorderly?”

Lagarde stood up to retrieve the espressos from the machine, when she suddenly changed her mind. She instead went to a small refrigerator hidden in the wood paneling of the wall and took out a bottle of La Grande Dame.

“How very appropriate,” Keynes laughed. “You must have heard, the one thing I regret in life…”4 He stood up and walked toward Lagarde.

“I found this in the fridge when I first arrived. I was saving it for a very special occasion. I think today qualifies,” Lagarde smiled, handing him a glass.

They toasted. “Tell me,” said Keynes, settling back in his chair. “How well did my bancor idea work? What did you call it? Special drawing right? You mentioned you made a large distribution a few years ago. Why was that?”

Lagarde stared at him blankly and then said, “Of course. You haven’t heard of the global financial crisis.”

“Indeed not! We had another Great Depression?”

“No. A decade ago, we had a major financial crisis that might have turned into a Great Depression. But luckily, we had learned your theories. The IMF advocated an immediate fiscal stimulus by all major economies as well as massive monetary easing.”

“And the slump passed?”

“More or less. The global economy has been a bit shaky ever since.”

“But the fiscal stimulus worked?”

“Yes, very well. Though some governments spent too much, and debt levels have soared.”

“And what of the monetary easing?”

“It was crucial.”

“But didn’t it result in hot money flows? Or, I suppose nowadays you have much better capital flow management?”

Lagarde shrugged. “There were large flows to developing and emerging market economies. And companies in those countries have increased their dollar exposure to dangerously high levels.”

“Productive capital should be allowed to go where it can be put to best use. But fully unfettered hot money flows…” Keynes shook his head in dismay. “White and I were in full agreement on that point when we were drafting the Articles, but then the New York bankers got hold of our draft and that was the end of it.5 Anyway, all this was a few years ago. What is the Fund dealing with nowadays?”

“So many problems,” Lagarde replied. “As I mentioned, even 10 years after the crisis, the world economy is still shaky. Plus, we’re dealing with a host of new issues: income inequality, achieving greater gender equity, global climate change.”

“Climate change? You mean the weather? How can the climate change?”

“The world produces thousands of tons of carbon dioxide every year, as well as other pollutants, and this has led to higher average temperatures, melting ice caps, rising sea levels…”

“My goodness,” said Keynes. “That sounds dreadful. But what does it have to do with the Fund?”

Lagarde explained. She was just finishing when there was a discreet knock and her assistant popped her head around the door. “Mme. Lagarde, you’re due to chair the Board in a few minutes.”

“Again?” Lagarde sighed. “OK. Thank you. I’ll be there in a moment.”

Keynes stood up. His moustache twitched into a smile. “I always said the Fund should have a nonresident Board.”

“Look, why don’t you spend the rest of the day at the Fund?” asked Lagarde, preparing to head out. “My assistant will show you around, and you can see for yourself how the Fund is doing. Come by and see me before you leave.”

* * *

Dusk was falling on what promised to be a beautiful Washington summer evening when Keynes returned to the Managing Director’s office.

“So, what do you think?” asked Lagarde.

“It seems to me that everything has changed. In my day, there were three constants: the weather; labor’s share of national income;6 and—I am sorry to say—women’s place in society.7 It’s all in flux now. Yet, at the same time, nothing has changed. The Fund still needs to help countries adjust to balance of payments problems without ‘resorting to measures destructive to national or international prosperity.’ It still needs to help achieve an equitable burden of adjustment between surplus and deficit countries and to manage volatile capital flows between source and recipient countries. And, on occasion, it still needs to regulate global liquidity. The only thing that’s changed is the nature of the shocks and problems that countries confront. But the fundamental mission of the Fund—helping its member countries cope with these problems—remains the same. Our real achievement at Bretton Woods was not in setting up the system of par values and fixed parities. It was in setting up an institution that could—and would—adapt to serve its membership.”

“Quite so,” replied Lagarde. “Come, I will walk you out.”

They rode the elevator in silence, lost in thought.

“Any other observations?” asked Lagarde, as she shepherded Keynes through the door.

“Yes,” replied Keynes. “When I see men—and women—of every race, of every nationality, and of every creed working together for the common good, I know that the IMF is in good hands.8 And,” he smiled, “when the IMF is in good hands, the world is in good hands.”

With a slight bow, Keynes turned and walked away, disappearing down 19th Street, NW.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.

References:

Adams, Timothy. 2005. “The IMF: Back to Basics.” Speech delivered at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, September 23.

Council of Kings College. 1949. John Maynard Keynes, 1883–1946, Fellow and Bursar: A Memoir. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Ghosh, Atish R., Jonathan D. Ostry, and Mahvash S. Qureshi. 2019. Taming the Tide of Capital Flows. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Helleiner, Eric. 1994. States and the Re-emergence of International Finance: From Bretton Woods to the 1990s. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Keynes, John M. 1924. A Tract on Monetary Reform. London: Macmillan.

———. 1939. “Relative Movements of Real Wages and Output.” Economic Journal

49

(193): 34–51.

Notes:

1 Keynes’s surprise is understandable: until the ninth quota review (1990), the United Kingdom had the second largest quota, after the United States. In 1947, the five countries with the largest quotas were the United States (31.68 percent), the United Kingdom (15.12 percent), China (6.56 percent), France (6.28 percent), and India (4.85 percent).

2 As Keynes (1924, 80) famously said, “In the long run, we are all dead.”

3 Adams (2005).

4 Keynes reportedly once said that his only regret in life was that he had not drunk more champagne (Council of Kings College 1949, 37).

5 See Helleiner (1994); and Ghosh, Ostry, and Qureshi (2019), Chapter 2.

6 Keynes (1939) called the stability of labor’s share of national income “one of the most surprising, yet best-established facts in the whole range of economic statistics.” Since the 1980s, however, labor’s share has been declining in most advanced economies.

7 Keynes was a strong supporter of women’s rights, becoming vice chair of the Marie Stopes Society in 1932.

8 On September 25, 1946, long before its member governments had adopted similar legislation, the IMF Executive Board adopted Rule N1: The employment, classification, promotion and assignment of personnel in the Fund shall be made without discriminating against any person because of sex, race, or creed.