Car plant in Kragujevac, Serbia. Although economic activity is picking up, reforms have to accelerate to close the gap with Western Europe (photo: Bloomberg/Contributor)

Central and Eastern Europe: A Broader Recovery, But Slower Catch-Up with Advanced Europe

May 11, 2017

Economic growth is broadening in Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe (CESEE). Further ahead, however, growth prospects will be tested by a dwindling workforce and weak productivity. Reaching Western European income levels would thus take longer, says the IMF in its Regional Economic Issues update on the region.

Related Links

Over the past year, growth spread widely in the region as Russia began its exit from recession. Overall growth is expected to be 2.2 percent in 2017, jumping from 1.5 percent in 2016.

Outside the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), activity slowed in 2016. Turkey suffered from domestic and external shocks, while growth in the rest of the region slowed in the second half of 2016, primarily due to a slower start of the utilization of European Union funds under the new EU budget cycle. Nevertheless, economic indicators signal that a pick up is underway.

Higher commodity prices helped the Russian economy to recover from the second half of 2016, after two years of recession. Prospects are also improving in Ukraine.

For the next couple of years, the outlook is slightly more favorable than forecast last November as global economic activity, which supports demand for the region’s exports, has improved. Investment is also set to gear up as the new cycle of the multiannual EU budget brings more investment funding for the region’s EU members.

Catching up may take longer

Despite the humming of economic activity in the region, convergence between the Western and Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe nonetheless is likely to take longer than previously thought. That is because the longer-term potential growth (the highest sustainable output growth expected of an economy) in most of the countries in Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe is still significantly lower than it was prior to the global financial crisis.

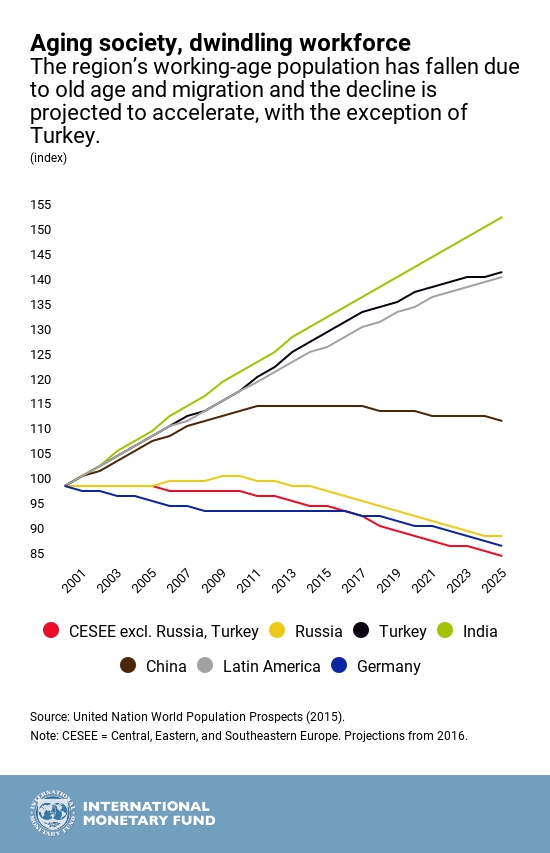

The culprits for low potential growth are weak productivity growth (productivity shows how efficient production is) and low investment rates, exacerbated by a rapidly aging population.

Most of the region’s workforce is shrinking due to aging, but also due to outward migration. Over time, the growing number of pensioners and the dwindling workforce would lower growth and widen budget deficits.

Risks

There are both upsides and downsides to the near-term prospects. On the positive side, growth can get stronger as the region benefits from stronger growth of its trading partners. On the negative side, risks stemming from higher interest rates in advanced economies could trigger capital outflows from countries in Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. Over the longer term, weak growth in Western Europe and increasingly inward-looking policies globally, with a possible retreat from cross-border integration in reaction to rising public discontent, could damage income growth in the region.

Double down on reforms

Many governments in the region should therefore make use of the current uptick in activity to reduce their debt, and to create buffers for higher social spending in harder times.

In addition, to accelerate income convergence toward advanced European levels, these countries must increase their productivity and investment. The IMF suggests concentrating on the following reform areas:

- strengthening institutions (protection of property rights, legal systems, and health care);

- improving the efficiency of the public sector (including through the restructuring of state-owned enterprises and improving oversight); and

- increasing labor participation (by increasing female participation and reducing incentives for early retirement).

The Regional Economic Issues report is published semi-annually. It is part of the series of Regional Economic Outlook reports.