How can Europe Pay for Things it Cannot Afford?

November 4, 2025

Thank you, [Mr. Kisselevsky], for the kind welcome and to the ECB for hosting us once again here in Brussels at the House of the Euro.

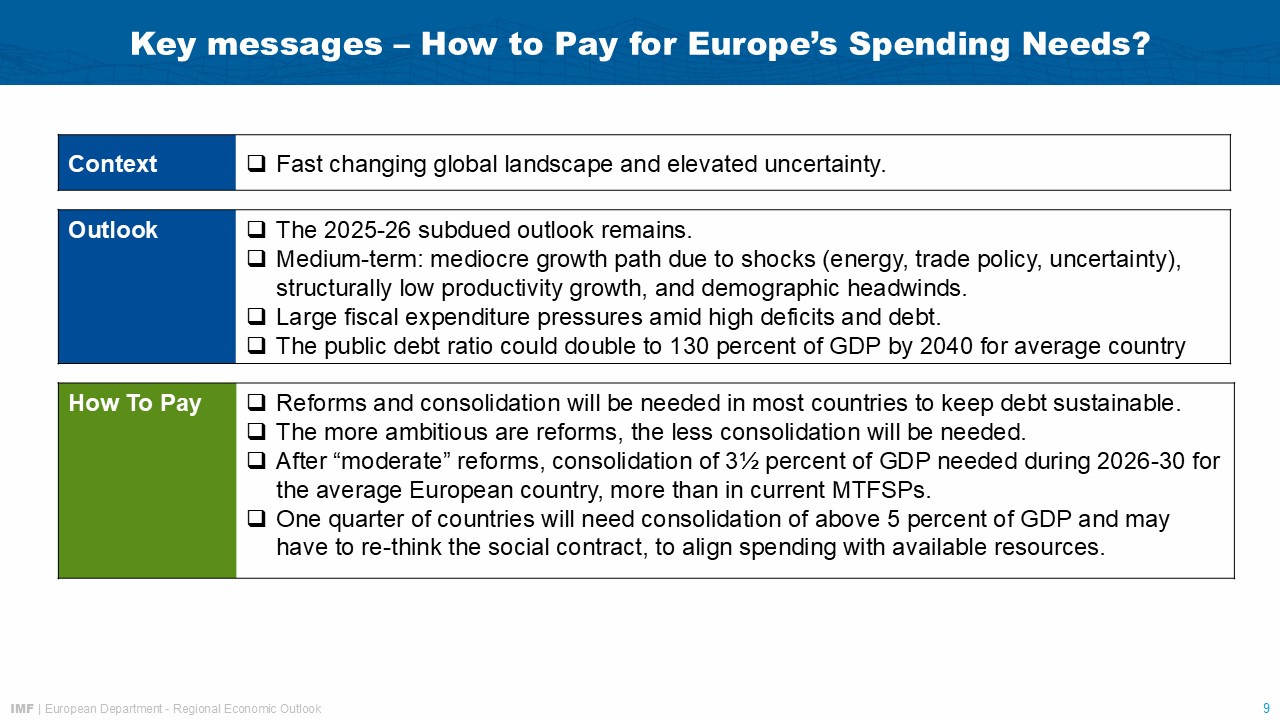

The year 2025 marks a period of profound transformation in the global economy, shaped by shifting trade policies.

For Europe, these developments follow a series of crises—from the pandemic to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—that have tested the region’s resilience.

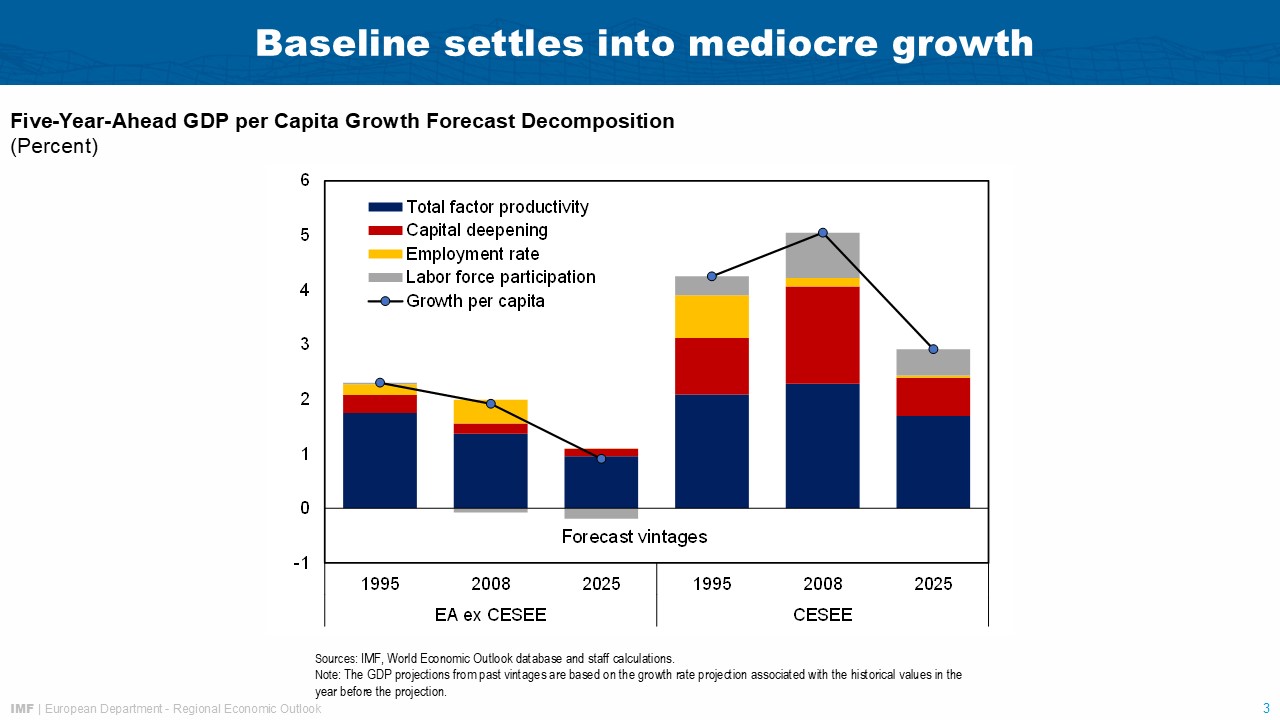

Timely policy action helped Europe avoid the worst, and the region continues to grow. Yet, as you know, the medium-term growth outlook remains mediocre.

My message today is that this has serious implications for Europe’s fiscal challenges. Put simply, unless Europe acts decisively to lift growth to a higher level, traditional fiscal consolidation measures will not be enough to prevent debt levels from becoming explosive, putting Europe’s social model at risk.

But let me begin by setting the stage and discussing our baseline outlook.

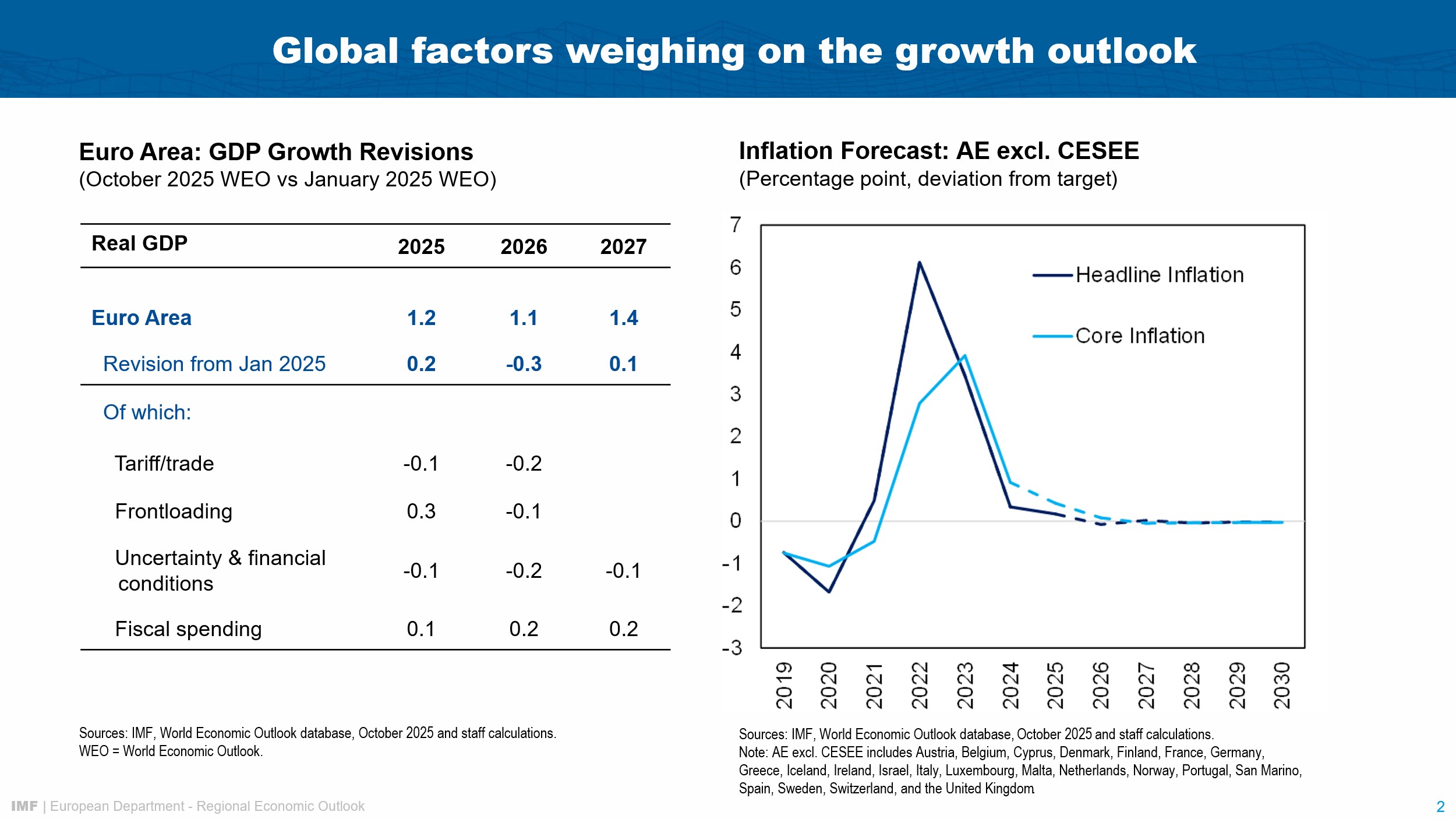

In our just-released October forecast, we slightly raise euro area growth projections for 2025 to 1.2 percent. However, the improvement is short-lived, with several factors weighing on the recovery in 2026.

The large front-loading of exports to the U.S. earlier this year is now reversing, and uncertainty remains high. Tariffs will increasingly squeeze export profits.

The preliminary flash estimate for Q3 released last Thursday broadly confirms this outlook.

Our medium-term forecast points to mediocre growth, due to persistent structural challenges that constrain Europe’s economic dynamism. Today, EU GDP per capita is nearly 30 percent below that of the U.S., and without meaningful reform, the gap will widen further.

Let me highlight three key areas:

- Structural Barriers: Intra-EU trade barriers remain significant—44 percent for goods and 110 percent for services. Regulatory frictions limit cross-border mobility of capital and labor while the absence of a unified energy market keeps costs high and undermines energy security and resilience.

- Demographic Headwinds: Europe’s population is aging. By 2050, over two-thirds of EU countries will see a decline in their working-age population, heightening the urgency of the reform agenda around labor markets and skills.

- Investment Gaps: In several countries, especially in the CESEE region, large investment shortfalls are depressing labor productivity and growth. Both EU-level and domestic reforms to deepen capital markets and incentivize private investment are essential.

European policymakers recognize the urgency to act. But progress has been slow. That needs to change.

Which brings us to the key question, “How Europe is going to pay for the things it cannot afford?”

We all know the region’s difficult fiscal landscape—high debt levels in many countries and rising spending pressures.

But the situation is worse. Europe’s fiscal challenges will become more pressing, for several reasons.

First, new demands on public spending have emerged in defense and energy security, adding to growing pension and health care costs.

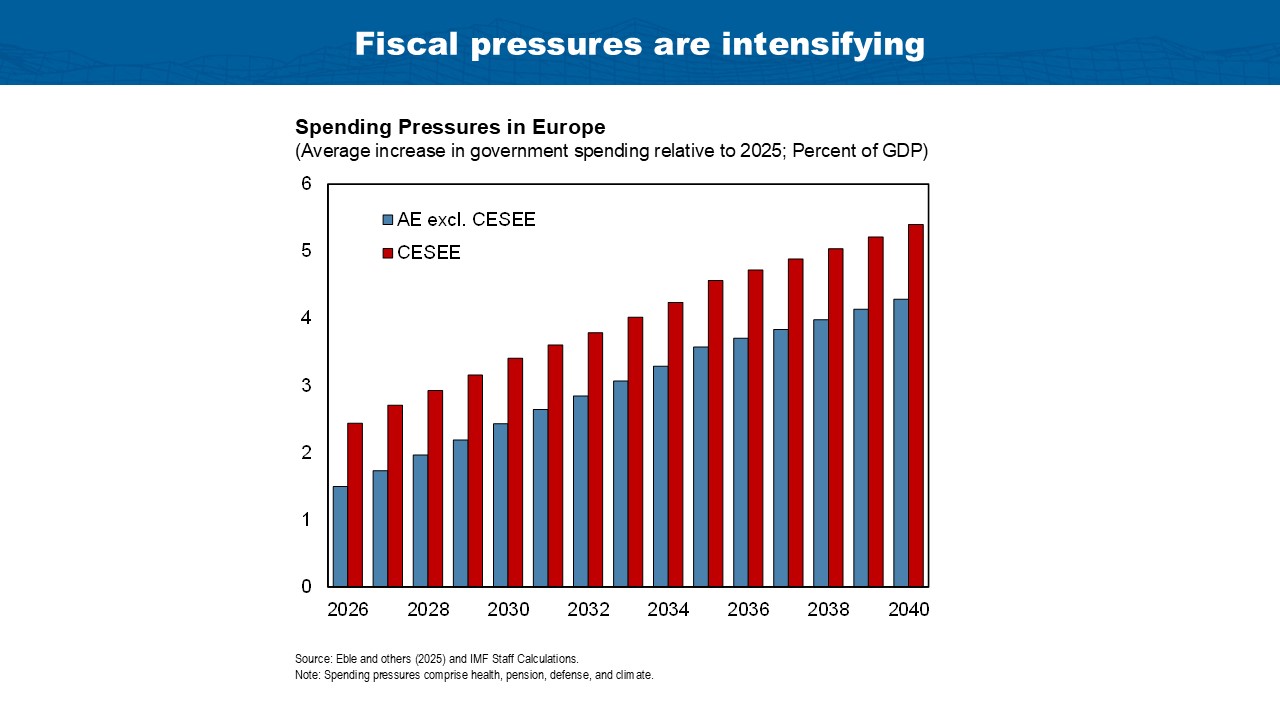

We estimate additional spending in these four areas at 4½ percent of GDP by 2040 in Advanced Europe including the UK but excluding CESEE economies (AE excl CESEE), and 5½ percent of GDP in CESEE countries.

Second, rising bond yields are also pushing up interest costs.

Third, the mediocre outlook for medium-term growth and labor supply weighs on revenues and puts upward pressure on debt levels.

Doing nothing is not an option!

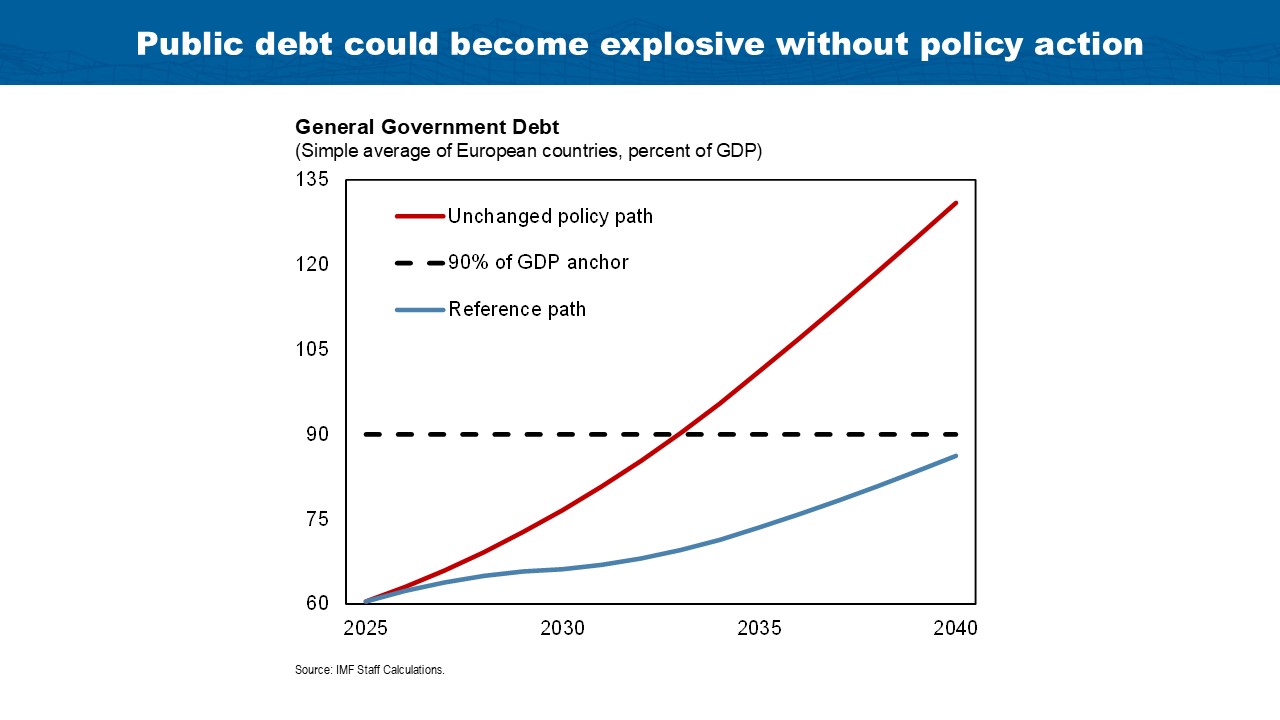

Our simulations show that under current policies, public debt would be on a steeply-increasing path over the next 15 years, with average debt ratios across European countries reaching 130 percent by 2040.

How big of a problem is this?

For the purposes of our simulations, we use a sustainable reference debt path that—over the longer term—does not exceed 90 percent of GDP. This benchmark reflects increased debt-carrying capacity in many countries over the past three decades.

It suggests an enormous sustainability gap: if no action is taken, by 2040, average debt ratios could exceed sustainable levels by 40 percentage points.

So, the question is, how to prevent debt from becoming rapidly unsustainable, while absorbing rising spending pressures?

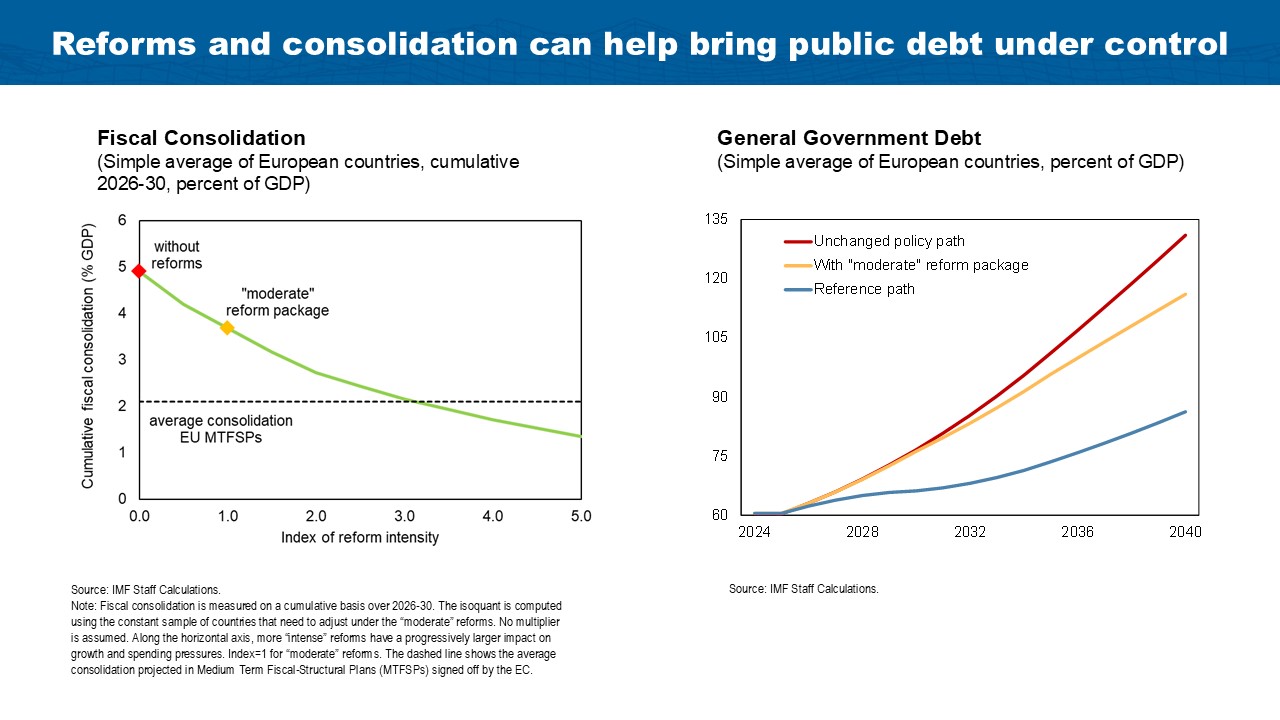

Closing a sustainability gap that large through conventional fiscal consolidation alone would be extremely difficult. Without reforms, the required deficit reduction to bring debt in line with the reference path would be almost 1 percent of GDP per year for five years, a cumulative 5 percent of GDP.

This far exceeds what past European consolidation efforts have achieved. Successful consolidation campaigns yielded cumulative savings of just about 3 percent of GDP over 3-4 years.

As any finance minister knows, sustaining a fiscal effort generating 3 percent of savings is an enormous political effort. Achieving 5 percent would be nearly impossible and would require deep cuts into the European model and social contract.

The solution lies in faster growth. In our analysis, we show that even a set of moderate reforms can make a substantial difference. It includes:

- growth-enhancing domestic reforms that close one quarter of the gap with top-performers;

- taking first steps to deepen the single market and increase the EU budget for public goods such as innovation and defense, financed through joint borrowing;

- pension reforms to stabilize spending;

- and measures to catalyze private investment through public investment banks.

This moderate reform package would reduce cumulative adjustment needs from around 5 to just above 3.5 percent—bringing the average debt path one third of the distance to the sustainable path.

Not all countries are the same, and some have lower starting levels of debt or less fiscal pressures to deal with. Still, about three-quarters of European countries would need to consolidate even after implementing the “moderate” set of reforms.

The average adjustment implied by our analysis notably exceeds what countries have committed to in their Medium-Term Fiscal and Structural Plans under the EU fiscal framework. For instance, the average adjustment under submitted and signed off plans would fall about 2 percent of GDP short of our estimates.

But let me be clear that more reforms could change this picture. In forthcoming work, we show that an all-out reform drive could make a significant contribution to closing Europe’s GDP per capita gap with the U.S.

This would obviously reduce the need for fiscal consolidation compared with the scenario we have modeled here.

Yet, for some high debt countries, even combining reform and conventional consolidation may not suffice.

Around one-quarter of European countries would still need to consolidate by more than one percent of GDP per year for five years, after implementing the “moderate” set of reforms. This, as I pointed out already, is well above what proved feasible in the past.

These countries will therefore face hard choices about the role and scope of government given the available resources.

In some cases, this may mean rethinking aspects of the European social model.

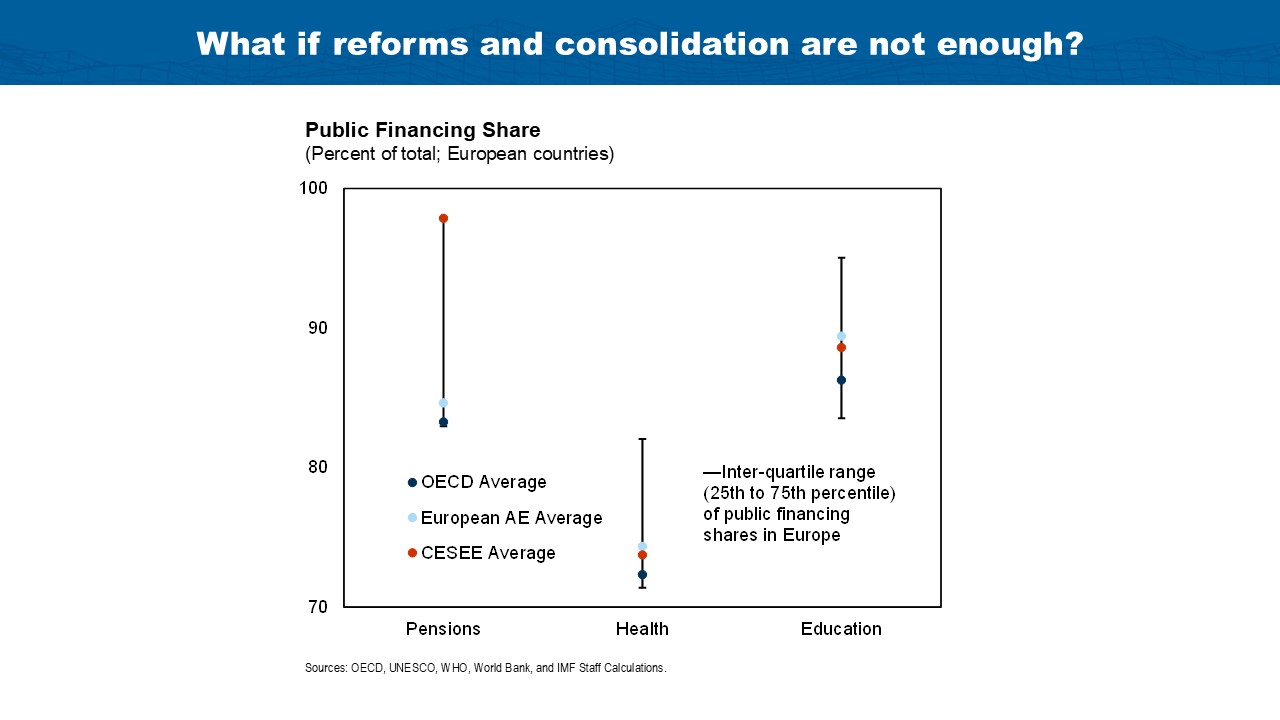

For example, if resources are truly limited, providing public services without cost might no longer be affordable. Instead, private financing could be increased while protecting the most vulnerable. Modest user fees for some services, like health care, could be introduced while maintaining free access for low-income groups.

Large tax reforms can also be designed in a progressive way, which is particularly relevant for CESEE countries. They have more room for revenue mobilization. Privatization of SOEs is another option to create fiscal space without hurting those least able to bear the costs.

The potential savings from those fundamental changes are large. If all European countries were to reduce the share of public financing in health, education, pensions, infrastructure and energy security to the OECD average, they could save up to 3 percent of GDP on average.

So, what does this tell us about how Europe can afford what seems unaffordable?

First, there are no silver bullets. Most countries will need a mix of reforms and fiscal consolidation.

Second, it is time to stop muddling through. Tinkering at the margins will not keep debt sustainable—and it would still provoke political backlash. Europe needs a coherent, ambitious strategy that combines significant reforms with sizable fiscal consolidation.

Finally, how reforms and consolidation will be implemented will determine success.

Clear communication and broad stakeholder dialogue that highlights the economic and social benefits of avoiding a more painful and disorderly correction forced by financial market pressure are essential.

Bundling policies to share benefits and distribute burdens fairly will help secure durable support.

And careful sequencing could ensure that the burden of reform does not become overwhelming.

Such an approach can deliver a sustainable fiscal path and a more dynamic Europe.

But time is short: Delaying such a package by 5 years would raise the required fiscal adjustment by another 1½ percent of GDP.

This is too high a price for inaction.

Thank you.

IMF Communications Department

MEDIA RELATIONS

PRESS OFFICER:

Phone: +1 202 623-7100Email: MEDIA@IMF.org