Debt and Entanglements Between the Wars a book edited by Era Dabla-Norris

December 19, 2019

- As Prepared for Delivery -

I want to thank the organizers of the ECB’s biennial Conference for the invitation to address you. It is truly an honor for me to be here. I am particularly happy that it gives me the opportunity to present to you the book Debt and Entanglements Between the Wars, edited by Era Dabla-Norris[1], that was just been put out by the IMF. The publication coincides with the publication of Sovereign Debt: a Guide for Economists and Practitioners, edited by Ali Abbas, Alex Pienkowski and Kenneth Rogoff. The simultaneous publication of two important titles on public debt highlights the relevance of the topic today.

From my own viewpoint the project started with Tom Sargent’s Nobel Lecture (Sargent, 2013) and the subsequent inaugural Richard Goode Lecture in 2015. From the viewpoint of the IMF work on historical time series for sovereign debt had already been on-going. Abbas et al. 2014 would be released shortly after I joined the Fund. Era Dabla-Norris, the editor of the book, was the entrepreneurial force bringing and keeping the various moving pieces together.

Debt and Entanglements: What’s in a title?

George Washington in his farewell address recommended to stay clear of “permanent alliances”. Thomas Jefferson followed suit in his first inaugural address. Enumerating the fundamental principles of his administration he noted: “Peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations – entangling alliances with none.” (emphasis added)

George Hall and Thomas Sargent, in their chapter Complications for the United States from International Credits in the new IMF book, build on an early insight from Henry Carter Adams (1887) on the perils of entanglements. Adams was a professor of Political Economy at the University of Michigan. Writing in 1887, Adams, in the tradition of Washington and Jefferson, warned Americans that:

“The granting of foreign credit is a first step toward the establishment of an aggressive foreign policy, and, under certain conditions, leads inevitably to conquest and occupation.”

Foreign credit is here identified as a source of diplomatic and political complications. Adams’ prophecy was soon to come to pass as New York competed with London for the mantle of the world’s financial capital. Hall and Sargent describe how American banks and private investors purchased billions of dollars of British and French government bonds between 1914 and 1916, prior to America’s entry into the war. But these large sums made German authorities predict that private American financial interests would soon impel the US to enter the war against Germany. Entry into the war, however, led the US government to provide even more loans to Britain, France, Italy, and other allies. And, insistence that these war debts be repaid ensured that Britain and France, would seek to exact reparations payments from Germany to service its debt obligations to the US The web of entanglements spread further and wider than could have been imagined even by the most far-sighted of scholars.

Hall and Sargent include in their chapter the full transcript of a letter by Secretary of State, William Jennings Bryan to President Woodrow Wilson, on the prospect of lending to France, by J.P. Morgan. Bryan had already publicly denounced lending to belligerent parties as incompatible with the true spirit of neutrality. In the letter to the President, he was seeking support for the Department of State’s position. Bryan writes that “money is the worst of contrabands because it commands everything else”. In the remainder of the letter he argues that financial interest will nudge the political system towards war. The President rejected Bryan’s prudence. The letter is dated August 1914. In June of the following year Bryan resigns.

I cannot avoid mentioning that 10 years later, the US administration was trying to hold the fiction that there was no involvement of the Coolidge Administration in the Conference on Germany. Private American representatives were involved: Charles Gates Dawes and Owen Young. Both were close to J.P. Morgan (Chernow, 1990). Eventually, the Dawes Plan and the Young Plan, were adopted as coordinated attempts to manage Germany’s debts and reparations. Entanglements were spreading far and wide. It is difficult to imagine a more complicated set of circumstances.

But the forces at play are of general relevance. International creditor nations like, for example, China and Germany can bear witness to the political challenges and complexities of international financial entanglements.

In my talk this evening, I will start by telling you what’s in the book and why we should care about the period between the two wars. Then I will use three little stories to illustrate the three adages that Tom Sargent uses to conclude his foreword to the book: first, “monetary policy has the power to convert bad loans into good ones”; second, sometimes, fiscal crises provoke political revolutions; and, finally, “the law of unintended consequences”.

What’s in the book? What’s the point of looking at the period between the wars?

The six of the seven chapters in the book focus on individual countries: US, the UK, France, Italy, Germany and Japan. Chapter 3 – the exception – covers four Dominions of the British Commonwealth (Australia, New Zealand, Canada and Newfoundland). They describe how politics and social dynamics influenced fiscal and monetary policy. They shaped crises, defaults and quasi-defaults, international confrontations and alliances, the build-up and the winding down of debts and credits.

The book relies on a new debt database (compiled by End, Marinkov and Miryugin, 2019). The starting point for the compilation was data on domestic and external debt, compiled by the League of Nations.

As an aside, that brings into focus that one of the key functions of international organizations is to collect, validate and disseminate relevant information.

The League of Nations data had to be complemented by national and other sources, e. g., Moody’s. The database includes information on the nature of the instrument, coupon rates, maturity dates, currency of denomination and taxation. The database includes about 3800 debt instruments, issued by 18 countries, for the period 1913 – 1946. A relevant omission is the absence of secondary market price data for most countries and instruments. Pioneering work by Hall and Sargent, for the US, and Ellison and Scott allow the computation of market valuation for debt. Market values are systematically used in chapters 1 (Hall and Sargent) and chapter 2 (Ellison, Sargent and Scott).

In chapter 1, Hall and Sargent find that, for US Federal Debt in the hands of the public, book values and market values track each other within a +/- 10% band. This applies over the full period 1910 – 1940. This results from fiscal, monetary and debt management policy choices (as documented by the authors).

Following Hall and Sargent the remaining six chapters in the book also try to tell stories, based on theory, bringing together macroeconomic and political events. But, on occasion, the interpretations in the chapters are difficult to reconcile with the patterns predicted by theory. The period confronted political systems and decision-makers with unprecedented difficulties. The period between the wars is quite literally a period in between. Ostensibly, a period between an old-world order, that governed the first period of globalization, and the order that would eventually emerge after the WWII. But it was also a period of transition from UK to US monetary and financial hegemony. It is amazing that, in 1914, the US was still a debtor nation. But, quickly after 1918, it was about to emerge - in the words of Max Winkler, a sovereign debt scholar from the 1930s - as the banker to the world.

Such momentous transitions offer ample material for study and reflection. By any measure, the frequency and magnitude of quasi-defaults and defaults is impressive. Forms included inflation, re-scheduling, moratoriums and re-structuring. Some governments privileged domestic creditors; others their foreign creditors. In some cases, the solution was mainly financial. In yet others, mainly legal and political. The period reminds me of the famous statement by Keynes (about international monetary arrangements): “in the interval between the wars the world explored in rapid succession almost, as it were, in an intensive laboratory experiment, all the alternative false approaches to the solution.”

One aspect that the experience between the wars makes evident is that monetary and fiscal policies necessarily interact. Connections via the respective budget constraints or balance sheets make such interactions unavoidable. The question then becomes: how will such interactions take place? Bassetto and Sargent (2019) review the literature and explore a number of examples in detail.

The importance of the numeraire (monetary policy to the rescue)

Under the gold standard, the rules of the game involved the fixing of an official gold price. Domestic money was freely convertible into gold at that price. Whenever these rules were suspended – e.g. in case of war – it was understood that the suspension would be temporary and that convertibility would be restored to the traditional parity (see McKinnon, 1993). That is what the Bank of England did in 1821. It restored the gold parity at the level that had prevailed before the 1792 – 1815 wars. The US followed a similar approach when it went back to gold in 1879, after suspension during the Civil War (1861 – 1865).

The logic is intuitive: by restoring the pre-suspension parity, policy-makers laid the foundation for expectations that future suspensions would similarly be temporary. It is also a fact that restoration entailed deflation. These rules were sensible from the viewpoint of the sovereign’s long-term reputation for creditworthiness. In clearer wording: the rules were aligned with the interests of long-term creditors.

Playing by the rules of the game, returning to the pre-1914 certainties and recovering London’s lost ground, relative to New York, were behind the UK’s return to gold, in 1925, at the pre-WWI parity. Keynes captures well the nature of monetary – fiscal interactions:

“We have assumed since the war, largely under the guidance of the Bank of England, a policy of deflation, debt repayment, high taxation, large sinking funds and Gold Standard. This has raised our credit, restored our exchange and lowered our cost of living. On the other hand it has produced bad trade, hard times, an immense increase in unemployment involving costly and unwise remedial measures, attempts to reduce wages in line with the cost of living and so increase the competitive power, fierce labor disputes arising therefrom … We have to look forward, as a definite part of the Bank of England policy, to an indefinite period of high taxation, of immense repayments and of no progress towards liberation either nominal or real, only enhancement of the bondholders’ claim. This debt and taxation lie like a vast wet blanket across the whole process of creating new wealth by new enterprise.”

(quoted in Kynaston, 2017)[2]

The confrontation between the interests of creditors (“bondholders”), on the one hand, and debtors and taxpayers, on the other is in sharp relief. But so are debt and taxes as obstacles to general prosperity. The gold standard proved impossible to maintain. The UK abandoned gold in 1931.

But the most important episode was the abrogation of the gold clauses in public and private debt contracts, by the US, in 1933. The story, as narrated by Sebastian Edwards (2018), starts (in April, 1933) with President Roosevelt, barely one month in the job, requiring – by Executive Order - all persons and businesses to sell their gold holdings to the Federal Reserve, at the official price of $20.67, per ounce.

In 1933, Roosevelt was convinced that the devaluation of the dollar relative to gold was a necessary condition for restoring prosperity. Increasing commodity prices – in particular agricultural prices – was one of his most repeated political goals. But there was a difficulty. Most debt contracts in the US included a gold clause. That imposed to the debtor the obligation to pay “in gold coin”. The clauses were atavistic in the sense that they were first introduced into contracts, during the Civil War, when the “greenback” circulated in parallel with the currency backed by gold. When gold was restored in 1879 the clauses had become customary. But therein lied the catch: if the dollar were devalued against gold that would further penalize debtors: that included prominently the farmers and the Treasury. So, three months after the Executive Order, Congress passed a Joint Resolution, annulling all gold clauses from contracts past and future, private and public. On January 1934, Roosevelt officially devalues the dollar to $35 per gold ounce.

Litigation on the abolition of the gold clauses followed. The issue was finally resolved, by the Supreme Court, in favor of Congress and the Administration in 1935.

Farther away in Asia: one of the most successful combinations of monetary, exchange rate and fiscal policies that the world has ever seen.

Farther away in Asia, as described in Chapter 7 of the book, Japan too grappled with the politically charged decision of when to return to gold after World War I. Japanese holders of domestic government securities advocated policies to increase the value of the currency back to its pre-World War I value, ensuring them high real returns. In Japan’s case, an emerging market country of the time, confidence that the value of the currency would be stable, and that debt would not be inflated away, also provided assurances to the country’s external creditors.

But just as in the UK, the return to gold also proved fleeting for Japan in the wake of the worldwide financial turmoil and crippling domestic deflation and depression. In 1930 and 1931, although real GDP growth stayed marginally positive, nominal GDP crashed by about 10 percent each year, due to runaway deflation. With unemployment rising sharply, domestic support for internal devaluation and convertibility of the yen to gold at the pre-war parity evaporated. It is an interesting coincidence that the small minority that campaigned against the restoration of the yen to par drew on the views of Gustav Cassel but also Keynes [3]. It is also important to remember that the restoration of Gold was short-lived. The gold embargo was lifted in January 1930. But, as soon as the UK abandoned the gold standard, in September of 1931, the yen came under pressure. Shortly after, in December, the yen was off the Gold Standard [4]. Meanwhile political contestation rose. The government fell. And, after elections, the conservative party came to power.

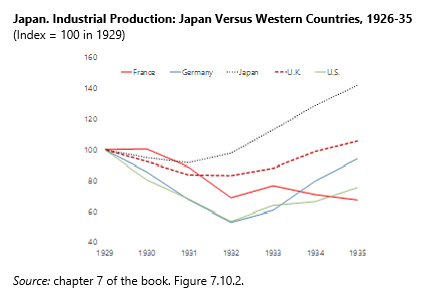

What followed was one of the most brilliant and successful combinations of monetary, exchange rate and fiscal policies that the world has ever seen (paraphrasing Kindleberger, 1973). Takahashi, the Minister of Finance, followed an expansionary fiscal policy and accommodative monetary and exchange rate policies. Public spending increased by 20 percent each year between 1932 and 1934. Policy interest rates were sharply lowered and the yen was floated (depreciated). Macroeconomic stimulus worked: deflationary expectations subsided and growth picked up. By 1935, in Japan, industrial production was well-above 1929 levels, contrasting with the UK, Germany, the US and France. Figure 7.10 is one of the most spectacular in the whole book. At the same time, during this period, the accumulation of public debt was moderate.

All this success was insufficient to make the military content. They aimed at unconstrained military spending. The military assassinated Takahashi in 1936. He was 82 years old.

Voting to end sovereignty.

The absence of public credit paves the way to revolution or, at least, to radical politics. Chapter 3 of the book includes a little-known pearl. The story of Newfoundland.

Newfoundland was a proud Dominion of the British Empire. In 1855, it became the first self-governing dominion with its own Executive Council and Legislature. In 1895, in the context of a banking and fiscal crisis, legislation was enacted making the Canadian dollar legal tender. At the same time, Canadian banks became dominant in Newfoundland’s financial system.

After 1931, Newfoundland found itself repeatedly at the verge of default. Having adopted the Canadian currency the territory was unable to devalue or inflate the debt away. After repeated close calls, the Amulree Commission recommended that assuming the aid was provided Newfoundland would renounce self-governance and accept reversion to colonial status. The British Parliament accepted the proposal of the Commission after a lively and controversial debate. The Commission’s proposals were also supported by the people, the commercial elite and the government of Newfoundland. In 1934, the legislature voted its own termination. The voluntary and formal subordination of democracy to creditors was unprecedented in the history of sovereign debt crises. In 1949, Canada assumed 90% of the debt and Newfoundland became Canada’s 10th province.

Unintended Consequences.

The book includes examples of dramatic unintended consequences and of the surprising effects of small details. My favorite example is from this period. It is not in the book. The story is due to Milton Friedman (1992).

President Roosevelt started a silver purchase program, in 1933, in the context that I have previously described. He was responding to farm and silver states’ interests. Silver had been at the center of the inflation debate in the US since the last quarter of the XIX century. The purchase program amounted to a silver subsidy and pushed the price up suddenly and sharply.

China had benefited from being on a silver standard in the early years of the Great Depression. The fall in the price of silver implied exchange rate depreciation. But the departure of many countries from the gold standard eroded this advantage in 1931. The situation was aggravated by the Japanese occupation of Manchuria. China was ruled by the Kuomintang and led Chiang Kai-shek. Building a strong army was a priority to resist the Japanese, pacify the war lords and eliminate the Communist rebellion. Chinese public finances were precarious.

The US silver policy produced a major deflation in China in the period 1934 -36. As early as the end 1935 abandoned silver and adopted far-reaching currency reforms. China was on a fiat paper standard. Inflation rose in China. First moderately. But, when the Japanese invaded in the summer of 1937, public spending exploded. Higher inflation and, eventually, hyperinflation followed. Friedman (1994, chapter 8) argues that the Chinese hyperinflation and the subsequent defeat of the nationalist government in China, at the hands of the Communists, is the perfect illustration of Keynes’ famous dictum: “there is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the basis of society than to debauch the currency.”

The triumph of communism in China was certainly not one of the intended consequences of Roosevelt actions to appease a few senators from Western – mining - states.

International complications and conclusion

In the winter of 1931, US President Hoover proposed a temporary moratorium that applied to war debts as well as to reparations. Congress approved this. In December of 1932, when the moratorium expired, country after country suspended payments. In the end, only Finland fulfilled her obligations in full. The cost to American taxpayers was considerable (Hall and Sargent provide detailed calculations).

Charles Kindleberger famously argued that: “the 1929 depression was so wide, so deep and so long because the international economic system was rendered unstable by the British inability and the US unwillingness to assume responsibility for stabilizing it.”

From such a perspective it is possible to look back at the 1920s and see British hegemony still looming in the context of the League of Nations. It included programs to stabilize the currencies of Austria and Hungary. But all of that was gone by 1931.

On July 1, 1944, the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, gathered at Bretton Woods. In the end the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD – “World Bank”) were created. An institutional approach to international economic and financial cooperation developed in the following decades. These developments have reflected the central place of the US.

And now what? The world is changing rapidly. Forecasts are difficult and unreliable. But, in any case, we can be sure that the difficulties in reconciling domestic politics and international credit relationships will remain. We will still be dealing with Henry Carter Adams’s entanglements derived from a complex web of debits and credits.

References

Abbas, Ali S. Laura Blattner, Mark De Broeck, Asmaa El-Ganainy, and Malin Hu, 2014, Sovereign Debt Composition in Advanced Economies: A Historical Perspective, IMF WP 14/162.

Abbas, Ali, Alex Pienkowski and Kenneth Rogoff (eds.), 2020, Sovereign Debt: a Guide for Economists and Practitioners, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Adams, H.C., 1887, Public Debts: An Essay in the Science of Finance, New York, D. Appleton and Co.

Bassetto, Marco and Thomas Sargent, 2019, Shotgun Weddings between Fiscal and Monetary Policy, available at http://users.nber.org/~bassetto/drafts.html

Chernow, Ron, 1990, The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance, Grove Press, New York.

Dabla-Norris, Era (ed.), 2019, Debt and Entanglements between the Wars, International Monetary Fund, Washington.

Ellison, M and A Scott, Forthcoming, Managing the UK National Debt 1694 – 2018, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics

End, N., M. Marinkov, and F. Miryungin, 2019, Instruments of Debtstruction: a New Database of Interwar Public Debt, IMF Working Paper, WP/19/26. International Monetary Fund. Washington, D.C.

Friedman, Milton, 1992, FDR, Silver and China, Journal of Political Economy, February.

Friedman, Milton, 1992, Money mischief, chapter 8, Harcourt Brace & Company.

Hall, G. and T. Sargent, 2011, Interest Rate Risk and Other Determinants of Post-WWII US Government Debt-to-GDP Dynamics, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 3: 192 – 214.

Hall, G. and T. Sargent, 2015, A History of US Debt Limits, Inaugural Richard Goode Lecture delivered by Thomas Sargent and available at https://www.imf.org/en/News/Seminars/Conferences/2016/12/30/Inaugural-Richard-Goode-Lecture-Thomas-J-Sargent-A-History-of-U-S

Hall, G. and T. Sargent, 2018, US Federal Debt 1776 – 1960: Quantities and Prices, Working Paper 18 / 25, Department of Economics, New York University, New York.

James, Harold, 2009, The Creation and Destruction of Value: the Globalization Cycle, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Keynes, John Maynard, 1931, Essays in Persuasion, Macmillan.

Kindleberger, Charles, 1973, The World in Depression, University of California Press.

Kynaston, David, 2017, Till Time’s Last Stand: A History of the Bank of England: 1694-2013, Bloomsbury, London.

McKinnon, Ronald, 1993, The Rules of the Game: International Money in Historical Perspective, Journal of Economic Literature, 31, 1, (March): 1-44.

Sargent, Thomas, 2013, Rational Expectations and Inflation, 3rd edition, chapter 10: United States Then, Europe Now, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Winkler, Max, 1933, Foreign Bonds: an Autopsy, Washington: Beard Books Reprint.

[1] I am grateful to Era Dabla-Norris, David Amaglobeli, Jacqueline Deslauriers and Phil Gerson for comments. All remaining errors are my own.

[2] The argument is the same as in the famous The Economic Consequences of Mr. Churchill. The essay was published in 1925 and included in Essays in Persuasion.

[3] A Tract on Monetary Reform was translated into Japanese in 1924.

[4] Gold exports were prohibited on December 14. The Gold Standard was suspended three days later.

IMF Communications Department

MEDIA RELATIONS

PRESS OFFICER:

Phone: +1 202 623-7100Email: MEDIA@IMF.org