Steering through the Fog: The Art and Science of Monetary Policy in Emerging Markets

May 7, 2025

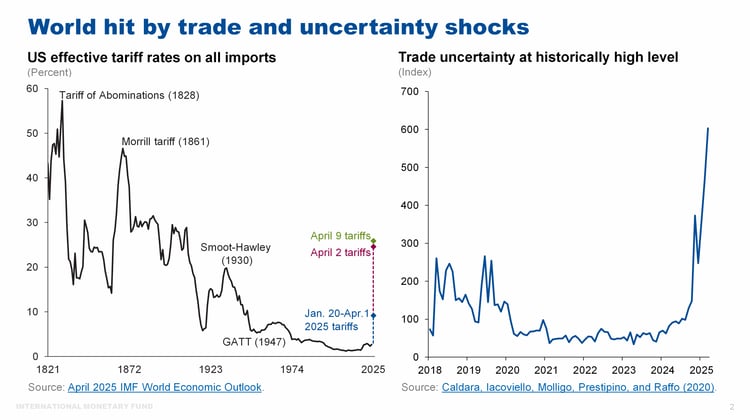

Good afternoon. It is a pleasure to be with you here at this critical juncture for the global economy. Since early April, the US effective tariff rate has increased to levels last seen over a hundred years ago, and the uncertainty surrounding trade policy and geopolitics has surged.

The economic effects of these developments are expected to be sizeable. Our World Economic Outlook ‘reference scenario’ projects that tariffs will reduce both global and emerging market (EM) output growth by roughly 0.5 percentage points relative to our forecast prior to the April tariffs. Countries imposing high tariffs, or those that are heavily dependent on trade with those countries, will be hit the hardest. But no country is likely to emerge unscathed: we have downgraded our forecasts for 127 countries that account for 86 percent of global GDP.

The impact on inflation is more varied. For countries facing higher tariffs on their exports, the tariffs are expected to mainly operate as a negative demand shock and exert mild downward pressure on inflation. For countries imposing much higher tariffs, notably the United States, the tariffs will likely act more as an adverse supply shock, boosting inflation while lowering growth.

There are several reasons why economic outcomes could be much worse than our WEO reference scenario. As of now financial conditions have not tightened much, including in emerging markets, and many EM currencies have remained surprisingly resilient against the dollar. If, however, trade policy discussions do not yield lower tariffs soon, financial conditions could tighten abruptly, with major effects on capital flows to EMs. Knightian uncertainty abounds as the global economic order transforms. How should central banks in emerging markets steer through this fog? I will address this question in today’s lecture.

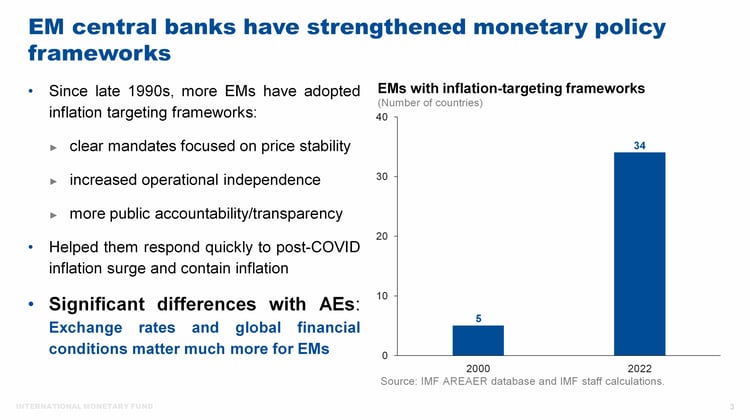

EM central banks have developed much stronger monetary policy frameworks since the late 1990s, often in the context of adopting inflation targeting. They have benefited from major improvements in governance, with clear mandates focused on price stability. Their operational independence has also increased substantially -- both de jure and de facto -- and they have strengthened their public accountability, as well as transparency. These advancements were invaluable in helping them respond quickly both to COVID and to the subsequent inflation surge, raising interest rates sharply in the latter case to contain inflation and keep inflation expectations anchored.

Even so, significant differences remain between EMs and AEs, especially regarding the strength of the exchange rate channel and the degree to which global factors influence monetary transmission. Several features deserve particular attention:

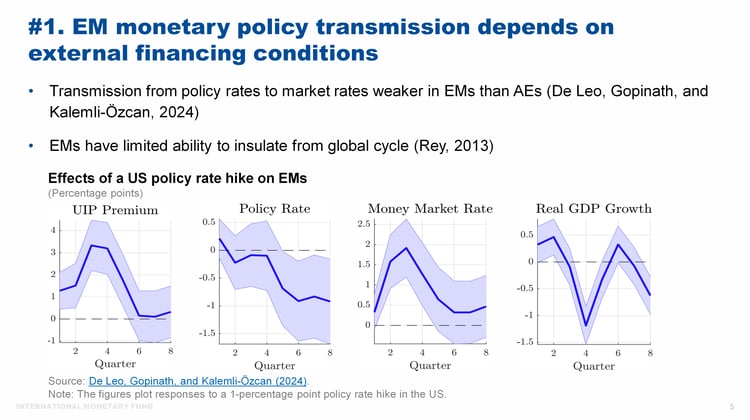

Transmission of policy actions and shocks differs in EMs

First, monetary policy transmission appears noticeably weaker in EMs than in AEs, and dependent both on global financial conditions and on the reliance of EM banks on external financing. In advanced economies, an easing of policy rates quickly translates into lower market rates -- which is what matters for the borrowing decisions of households and firms -- and this boosts the economy.

By contrast, my research with Sebnem Kalemli-Özcan and Pierre De Leo (De Leo, Gopinath and Kalemli-Özcan, 2024) shows that when EM central banks loosen policy, the transmission to short-term market rates depends critically on what happens to global financial conditions. If global financial conditions tighten enough – as often follows a surprise tightening in US monetary policy – then domestic market rates may even rise when the EM central bank lowers policy rates. The implicit rise in the risk spread facing borrowers clearly blunts the effectiveness of monetary policy and makes it harder for EMs to cushion the effects of shocks. This is particularly relevant at the current juncture where trade shocks could play out as negative demand shocks in many EMs, calling for looser monetary policy. At the same time, they could play out as negative supply shocks in the US and call for tighter US monetary policy.

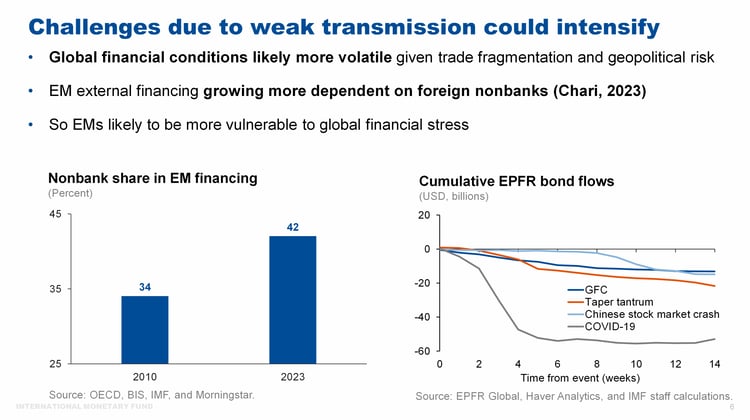

The changing mix of EM external financing also raises new vulnerabilities. EMs have become more dependent on external financing from foreign nonbank financial institutions, including insurance companies and investment funds, with their share of external portfolio financing growing to about 40 percent. While nonbanks help diversify emerging market funding sources and reduce borrowing costs, these types of capital flows are also very sensitive to the global financial cycle.[1] At times of financial stress, investment funds—such as exchange traded funds and open-end mutual funds in particular—are more susceptible to investors withdrawing their money, which in turn causes investment funds to withdraw from the riskiest markets. Consequently, the volume and speed of exit of capital flows have increased over time, as was evident at the start of Covid-19.

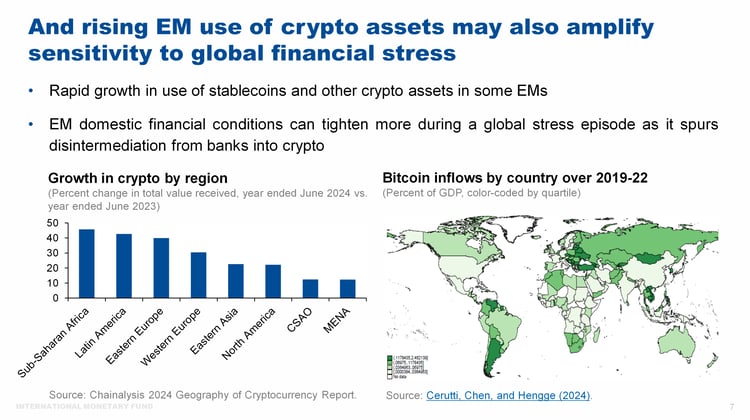

This sensitivity of EMs to global stress may also increase given that crypto assets are playing a larger role in cross-border financial intermediation and payments, often spurred by the desire to achieve cost-efficiencies, but also to circumvent capital flow restrictions in some cases. In most EMs, crypto asset use doesn’t yet appear high enough to present imminent systemic risks. Even so, crypto assets are growing rapidly in many EMs, and overall usage has become a noticeable share of GDP in some EMs with high inflation and lower macroeconomic stability. For example, Cerutti, Chen and Hengge (2024) find that several EMs in Latin America and Eastern Europe fall in the upper quartile of countries in terms of the magnitude of their bitcoin inflows as a share of GDP, with monthly inflows in the range of 0.1 to 0.8% of GDP. Focusing on a wider set of crypto assets, Cardozo, Fernández, Jiang and Rojas (2024) find that cross-border crypto outflows have reached as much as a quarter of gross portfolio outflows in Brazil.

Use of crypto requires a careful understanding of the risks. Crypto may increase capital flow volatility and exacerbate financial stress, including by allowing investors to easily shift their deposits out of domestic banks into foreign exchange-denominated stablecoins. If crypto flows grow large enough, such disintermediation from the banking system and associated capital outflows could cause financial conditions to tighten and the exchange rate to weaken, and potentially spur a significant economic downturn.

Weaker policy credibility complicates monetary policy trade-offs

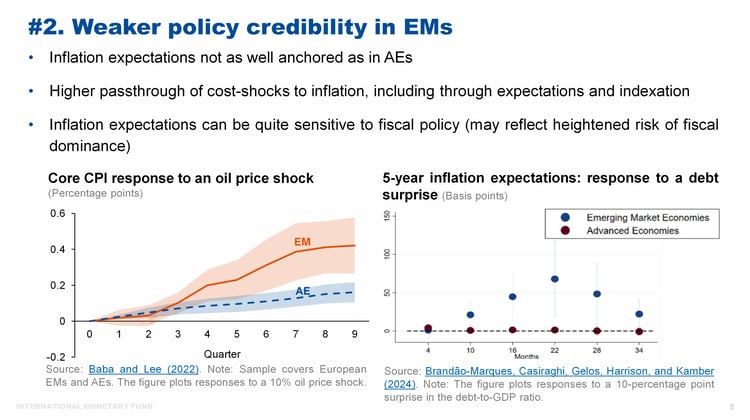

A second difference between AEs and EMs is the relatively weaker credibility of EM monetary policy to deliver low inflation. While EMs have improved their frameworks substantially, inflation expectations still tend to be less well-anchored than in AEs. Consequently, there is a higher passthrough of cost shocks to inflation, as they feed through much more into inflation expectations as well as through other channels such as wage indexation. Oil price shocks tend to impact core inflation more than twice as strongly in a sample of emerging market economies, relative to advanced ones.[2] This high passthrough makes dealing with external shocks particularly difficult for EM central banks, as second-round effects could be sizeable, including from ongoing shocks to trade policy that could disrupt supply chains and raise input costs.

Inflation expectations also tend to be more sensitive to fiscal policy and debt in EMs. This likely reflects increased risks of fiscal dominance and political interference in central bank decisions, which can undermine the public’s confidence in the central bank’s ability to fight inflation. A surprise increase in government debt tends to boost medium-term expected inflation in EMs significantly, while having little effect in advanced economies.[3]

Exchange rates have a much larger imprint on price and financial stability

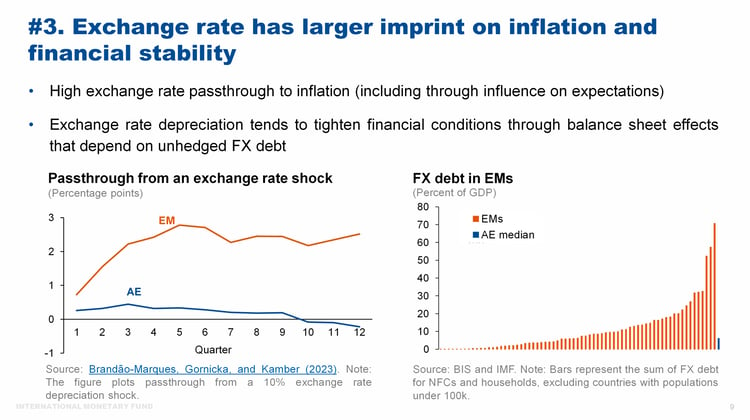

A third critical distinction between EMs and AEs is that the exchange rate has a much larger imprint on price and financial stability in EMs. While passthrough of exchange rate changes to inflation has declined considerably for many EMs, it remains significantly higher than in advanced economies. A 10 percent depreciation of EM currencies against the dollar causes EM price levels to rise by about 2 percent, several times larger than in advanced economies.[4]

The presence of foreign exchange mismatches increases the financial stability risks from exchange rate depreciation. While many EMs have reduced FX mismatches – or lowered the risk through the development of derivatives markets that allow for better hedging -- reliance on dollar funding within the financial system remains an important source of fragility for some EMs. This weakens monetary transmission, as lowering interest rates causes the balance sheets of corporates with unhedged FX liabilities to deteriorate and financial conditions to tighten, which offsets some of the stimulus from easing. EMs that have shifted to relying more on local currency financing also can experience sharp increases in currency premia and local borrowing costs when foreign investors exit these shallow markets. This makes it harder for EMs to deal with an environment of bigger external shocks: even if a tariff abroad would look like a demand shock from the standpoint of an AE economy, the exchange rate depreciation it induces raises risk spreads and makes it harder for the EM central bank to cushion the impact on the economy.

Steering through the fog: How should policy respond?

Having outlined some of the unique challenges emerging market central banks face in the current global context, I will next lay out some broad principles that can help steer through the fog. EMs clearly will differ in how they respond to the shocks and the uncertainty depending on their cyclical conditions and on structural features such as the extent of their exposure to trade and financial disruptions.

This said, and despite the fog, EM central banks should respond forcefully to upside inflation risks if they materialize to ensure that high inflation does not get embedded into inflation expectations. While I’ve noted that we see the current configuration of tariffs as likely to be slightly disinflationary for many EMs in our reference scenario, there is a significant risk that inflationary pressures could emerge -- from supply chain disruptions and higher input cost pressures in a fragmenting world or from exchange rate depreciations.

Given the high passthrough of both exchange rate changes and cost shocks to inflation in EMs, a major risk is large and persistent second round effects, especially if inflation has been running persistently above target and the fiscal position is weak. History has shown that once inflation becomes embedded in expectations—often through wage and price indexation mechanisms—it becomes significantly more difficult to reverse. If the risk materializes, timely and firm action is critical to keep inflation expectations anchored and reassure the public of the central bank’s unwavering commitment to sound monetary policy and price stability.

Foreign exchange intervention should be used prudently

Second, in a more turbulent external environment, foreign exchange intervention (FXI) can help address disorderly market conditions that undermine financial stability. The Fund’s Integrated Policy Framework is helpful in identifying conditions when it may be possible to improve tradeoffs facing central banks using FXI and other tools (IMF, 2023; Basu, Boz, Gopinath, Roch and Unsal, 2023).

Notably, central banks can reduce exchange rate pressures by selling FX during episodes of capital flight when FX markets are shallow, allowing central banks not to have to hike policy rates sharply. This can improve macroeconomic outcomes as well as lower financial stability risks.

However, it is important that FXI is not used to reduce exchange rate volatility per se, or to target a particular level of the exchange rate, as such misuse could easily weaken confidence in the central bank’s commitment to stabilizing inflation. Moreover, given the finite level of reserves, the bar for FXI should be high to ensure that FX liquidity can be provided when it is really needed. As of now financial conditions have tightened in an orderly manner, which means that when it comes to FXI the advice is to keep the powder dry.

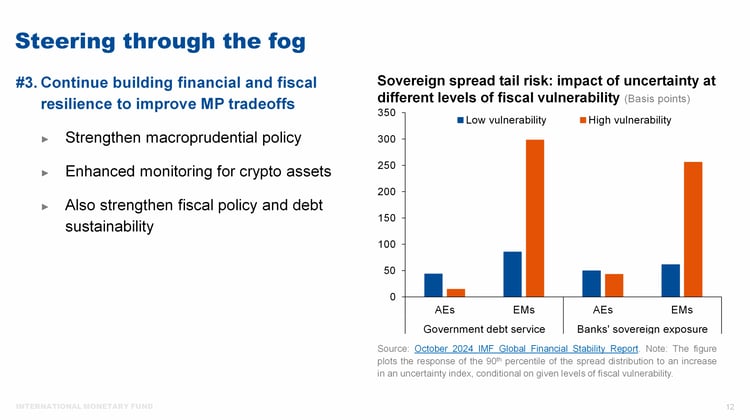

Build financial and fiscal resilience

Third, efforts to build financial resilience through strengthening prudential policies are also desirable. As I have emphasized, EM financial systems remain quite exposed to geopolitical shocks and face growing risks from heightened external finance from foreign nonbanks and potentially crypto. Prudential policies can help them build adequate buffers as well as reduce vulnerabilities arising from high leverage, volatile capital flows, and FX mismatches. On the crypto side, it will be important to develop comprehensive legal, regulatory and supervisory frameworks for crypto assets, including through cooperative global efforts given their cross-border nature (IMF, 2023b). The authorities should also ensure that capital flow management measures, when appropriate, remain effective and not undermined by the use of crypto. And EMs should continue to strengthen macroeconomic frameworks to reduce the risk of currency and asset substitution into crypto assets (often called “cryptoization”).

Fiscal policy also plays a critical role in helping ensure macroeconomic stability. Uncertainty shocks have much bigger effects on sovereign spreads when EM debt servicing costs are relatively high. Ensuring that tax and spending policies adjust to keep debt on a sustainable path helps provide buffers to respond to downturns and lowers financial stability risks.

Improve central bank communication, governance, and policy strategy

Lastly, there is a high premium on further strengthening policy frameworks to continue building resilience in a more shock-prone environment.

Clarity of communication has become more critical than ever. Effective communication about the central bank’s reaction function –in qualitative terms – is likely to be useful in helping better anchor inflation expectations and thus improve tradeoffs.

Improved governance – including to strengthen central bank independence – can increase public confidence that the central bank will have latitude to achieve its objectives. Central banks will inevitably make mistakes—no forecast is perfect. But what must be clear is that any deviation from target is the result of uncertainty, not political interference.

EM central banks, as for their AE counterparts, must also adapt their policy strategies to focus more on the distribution of outcomes rather than the modal outlook, and to take more account of risk management considerations. Monetary policy must navigate a world shaped by a multiplicity of shocks—some persistent, some temporary, and some with offsetting effects on inflation where it is difficult to assess the net impact.

Accordingly, many central banks should continue to take steps to revise their frameworks to move away from excessive reliance on central forecasts. This can be facilitated by increasing use of scenario analysis in decision-making.

Conclusion

To conclude, EMs have made major strides in improving their monetary policy frameworks, and this has enabled several of them to respond effectively to unprecedented shocks like the pandemic. They are now being tested again as the global economic order is reset and Knightian uncertainty prevails. This uncertainty does not, however, imply gradualism in all matters. If inflation pressures rise, EM central banks will need to respond quickly using policy rates to prevent higher inflation from getting entrenched as they did during COVID. We must recognize that the road ahead may have many unforeseen turns, which calls for further strengthening financial and fiscal resilience and navigating with monetary policy clarity, credibility, and discipline.

References

Baba, C., and J. Lee. 2022. “Second-round effects of oil price shocks – implications for Europe’s inflation outlook”. IMF Working Paper no. 2022/173.

Basu, S.S., Boz, E., Gopinath, G., Roch, F., and F.D. Unsal. 2023. “Integrated monetary and financial policies for small open economies”. IMF Working Paper no. 2023/161.

Brandão-Marques, L., Casiraghi, M., Gelos, G., Harrison, O., and G. Kamber. 2024. “Is high debt constraining monetary policy? Evidence from inflation expectations”. Journal of International Money and Finance 149(C).

Brandão-Marques, L., Górnicka, L., and G. Kamber. 2023. “Exchange rate fluctuations in advanced and emerging economies: Same shocks, different outcomes”, in Shocks and Capital Flows, edited by Gaston Gelos and Ratna Sahay, IMF.

Cardozo, P., Fernández, A., Jiang, J., and F.D. Rojas. 2024. “On cross-border crypto flows: Measurement, drivers, and policy implications". IMF Working Paper no. 2024/261.

Cerutti, E.M., Chen, J., and M. Hengge. 2024. “A primer on Bitcoin cross-border flows: Measurement and drivers". IMF Working Paper no. 2024/85.

Chari, A. 2023. “Global risk, non-bank financial intermediation, and emerging market vulnerabilities”. Annual Review of Economics 15: 549-572.

De Leo, P., Gopinath, G., and S. Kalemli-Özcan. 2024. “Monetary policy and the short-rate disconnect in emerging economies”. NBER Working Paper no. 30458.

IMF. 2023. “Integrated Policy Framework – Principles for use of foreign exchange interventions”. IMF Policy Paper no. 2023/061.

IMF. 2023b. “Elements of effective policies for crypto assets”. IMF Policy Paper no. 2023/004.