Canada Can Grow Faster by Unlocking Its Own Market

January 27, 2026

Knocking down internal trade barriers could boost output in Canada by 7 percent

Canada is one of the world’s most open economies. Over decades, it has built deep and resilient links to global markets, anchored in openness, predictability, and rules-based trade. Yet at home, the Canadian economy remains much less integrated than its global footprint would suggest. Goods, services, and workers face significant barriers when moving across provincial and territorial lines—a fragmentation that affects productivity, competitiveness, and overall resilience.

This is not a new diagnosis. Canada’s internal market has long reflected its federal structure, with provinces exercising constitutional authority over many of the policies that shape commerce. These include licensing, standards, procurement, and service regulation. Over time, regulatory differences and administrative frictions have accumulated, acting as barriers to scale, competition, and mobility—especially in services, where the economic opportunities, and costs, are highest.

With global growth under pressure and productivity constraints becoming more binding, the case for integrating Canada’s internal market has likely never been stronger.

Canada’s fragmented internal market

New evidence puts some numbers around a long-recognized problem. Using widely accepted trade analysis methods, we estimate that non-geographic, policy-related barriers within Canada average the equivalent of about a 9 percent tariff nationally. These costs are mainly concentrated in services—which account for the majority of interprovincial trade—with barriers in some sectors, including educational and healthcare services, exceeding the equivalent of a 40 percent tariff. Such a level would be prohibitive in most international trade agreements.

The burden is also uneven. Large provinces with diversified economies and dense networks face relatively low internal trade costs. Smaller provinces and northern territories face costs that are multiples higher, especially in services such as retail trade, health, education, and professional services. The result is a patchwork economy where geography and regulation jointly shape opportunity—and where advantages that normally come with scale are muted.

Large reform payoffs

These frictions are economically consequential. What would deeper internal integration deliver? According to model-based simulations, fully eliminating non-geographic internal trade barriers could raise Canada’s real GDP by nearly 7 percent over the long run—roughly C$210 billion in today’s terms. These gains are driven not by short-term demand effects, but by higher productivity: more efficient allocation of capital and labor, stronger competition, and better scale for high-performing firms. In other words, this is a gift that would keep on giving.

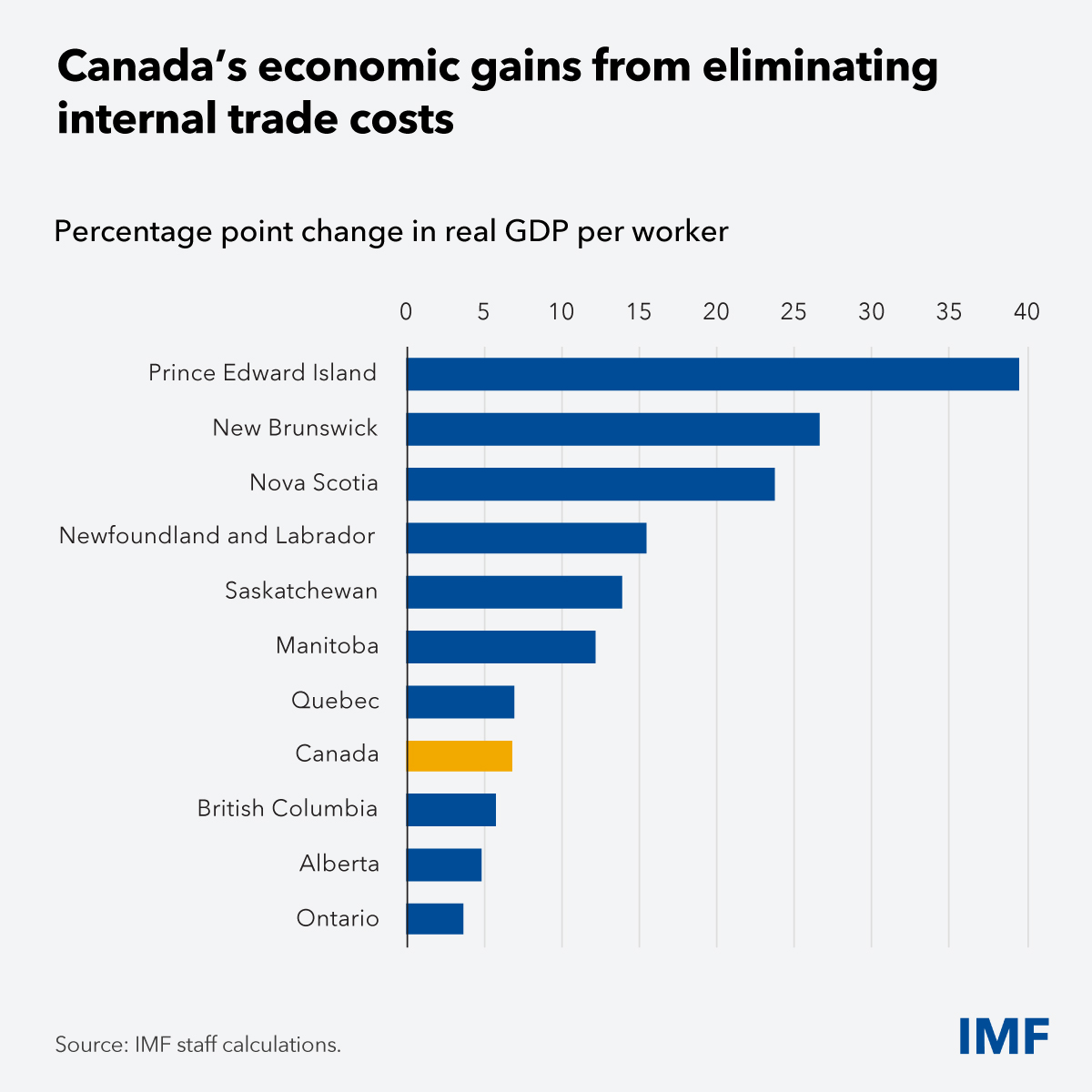

The distributional pattern reinforces the case for reform. Smaller and more remote provinces would gain the most in percentage terms, as their companies and workers gain access to larger markets. Atlantic Canada and the northern territories could see particularly large productivity gains. But larger provinces also benefit substantially in absolute terms, reflecting their central role in national supply chains. Internal integration is not a zero-sum reallocation—it is a national productivity dividend.

Services matter most. Roughly four-fifths of the total GDP gains would come from liberalizing services sectors. This reflects their growing weight in the economy and their role as inputs into nearly all other activities. For instance, barriers in finance, telecommunications, transportation, and professional services, which are essential inputs for most businesses, ripple through the economy, raising costs well beyond the sectors where they originate.

Prioritization matters

Full liberalization will take time. That makes prioritization essential. The highest-impact reforms are not necessarily in sectors with the highest measured barriers, but in those with the greatest economic influence—sectors that are heavily traded across provinces and deeply embedded in input-output networks.

Finance, transport, and telecommunications stand out as enablers of economy-wide efficiency, innovation, and competition. Progress here would amplify returns elsewhere: making it easier to start and expand a business, improving labor mobility, and supporting investment in high-productivity activities. It would also strengthen Canada’s capacity to absorb external shocks. Our analysis suggests that even modest reductions in internal trade costs could help offset sizable adverse shifts in external trade conditions, underscoring the role of domestic integration as a resilience buffer.

Making federalism work for a single market

The challenge revolves around implementation and coordination. With the federal framework largely in place, further progress depends on making cooperative federalism work more effectively. Mutual recognition should become the default, with narrow and transparent exceptions—starting with professional licensing and credential recognition. Benchmarking and public reporting of internal trade barriers can sharpen accountability and sustain momentum. Federal leadership can continue to play a catalytic role through incentives, conditional funding, and convening power—while fully respecting provincial jurisdiction.

Canada has navigated complex federal-provincial reforms before. Internal market integration can follow in that tradition: pragmatic, incremental, and anchored in shared national gains.

A moment to act

Canada’s economic future will be shaped as much by how effectively it mobilizes its domestic market as by how it engages globally. The evidence is clear: internal barriers remain large, economically costly, and increasingly out of step with the needs of a modern, vibrant, service-intensive economy. Removing them offers one of the most powerful—and least fiscally costly—levers to raise productivity, strengthen resilience, and support inclusive growth.

The opportunity is now. The prize is large. Turning thirteen economies into one is no longer just an aspiration—it is an economic imperative.

*****

Federico J. Díez is a senior economist in the IMF’s Western Hemisphere Department.

Yuanchen Yang is an economist in the IMF’s Western Hemisphere Department.

Trevor Tombe, Professor of Economics and Director of Fiscal and Economic Policy at the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy, also contributed to this research.