Typical street scene in Santa Ana, El Salvador. (Photo: iStock)

IMF Survey : Latin America’s Experience with Fiscal Policy

April 30, 2015

- Large fiscal buffers enabled many Latin American countries to respond to global crisis

- But higher spending was not reversed as growth recovered

- Key priorities: rebuild fiscal space to weather growth slowdown, restore stronger institutions

Latin America’s bold fiscal stimulus in 2009 cushioned the impact of the global financial crisis, but the increase in spending has proved difficult to reverse, even as growth recovered, according to a new IMF study.

Construction workers in Fray Bentos, Uruguay. Latin America’s fiscal policy reaction to the global financial crisis was useful in containing output losses, says IMF study (photo: Stringer/Newscom)

Staff Discussion Note

To weather the commodity cycle and other growth shocks, Latin America needs to rebuild fiscal buffers and strengthen fiscal institutions.

A new Staff Discussion Note—Fiscal Policy in Latin America: Lessons and Legacies of the Global Financial Crisis—looks at the region’s fiscal policy experience during the crisis and its aftermath. It focuses on the six larger, financially-integrated emerging market economies of Latin America—Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, and Uruguay—which account for more than 70 percent of the region’s output.

Incomplete reversal

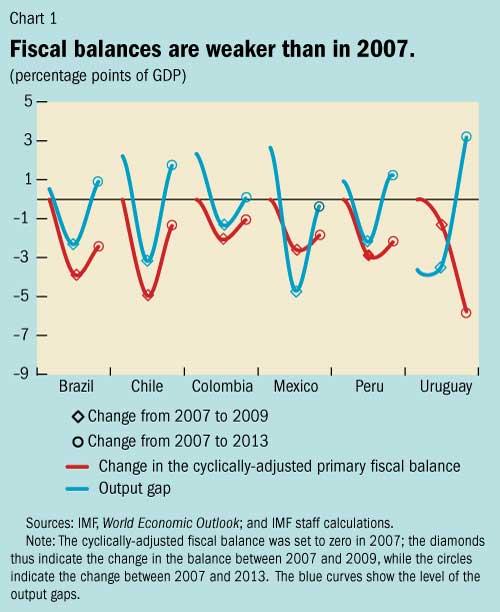

The study finds that the 2009 fiscal stimulus reduced output losses in these six countries by ¾ to 2 percentage points. More than six years later, however, cyclically-adjusted fiscal balances in most of the region are well below pre-crisis levels, even with the benefits of sizeable commodity revenues and strong growth in the years following the crisis (see Chart 1). And spending-to-GDP ratios are about 4 percentage points of GDP higher than in 2007, on average, mainly reflecting increases in current spending that have proved hard to reverse as growth recovered.

Crisis legacies

The resulting loss of fiscal space is now becoming a pressing concern, as the commodity cycle has turned and growth in emerging market economies weakens, the study warns. And this is occurring while public finances are already set to come under pressure over the medium term from aging populations and increasing demands for public services. In some cases, policymakers are becoming constrained in their ability to mount a proactive fiscal response in the face of an adverse growth shock while others are even being pushed toward a fiscal tightening that may exacerbate the economic cycle.

Another legacy of the crisis has been some erosion of fiscal policy institutions. Initially, many countries had to “bend their fiscal rules” to accommodate the 2009 fiscal stimulus. Subsequently, however, the relaxation of the fiscal frameworks became de facto permanent, underscoring the risks of making ad hoc changes to the framework without a medium-term anchor or exit plan.

Lessons from the crisis

The experience of Latin American countries since the global financial crisis reminds us that, to be effective, countercyclical fiscal policy cannot be a one-way ticket: it has to apply symmetrically during upturns and downturns.

Rebuilding fiscal buffers should be one of the main priorities going forward. The desired size, pace, and timing of the fiscal adjustment will vary across countries depending on debt dynamics, fiscal risks, the macroeconomic outlook, and market conditions. In some cases, the existing space still allows for the use of fiscal policy to counter negative shocks in the near term. In others, a quicker shift to deficit reduction will be needed even in cases where economic growth remains disappointing and below potential. Fortunately, some of this adjustment is already underway but more needs to be done.

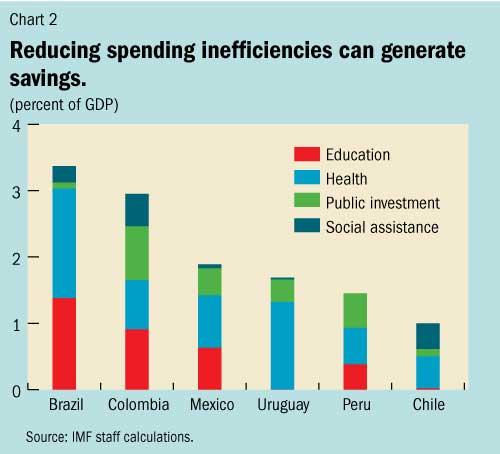

Raising the efficiency of public spending would allow governments to improve the quality of public goods and services while containing spending growth. The analysis of technical spending efficiency presented in the study highlights that these countries could potentially save 1–3½ percentage points of GDP by reducing inefficiencies in education, health, social assistance, and public investment (see Chart 2).

On the institutional front, reforms need to go beyond restoring the pre-crisis fiscal frameworks. The goal should be to build in features that avoid procyclicality (including through expenditure rules), ensure a more symmetric response to both downturns and expansions, and incorporate well-defined escape clauses. Strong adherence to policy rules is also important and independent fiscal councils could help in this respect by providing an objective public assessment of budgetary forecasts and monitoring compliance. Finally, the multi-year consequences of budget decisions taken today should be given more prominence in the public policy debate.